An Evangelical man named Will sent me an email today about a post I wrote in 2015 that took a close look at the finances of the American Family Association (AFA). Titled, Follow the Money: The American Family Association and their Support of the Gay Agenda, I took a deep dive into the incomes and expenditures of the AFA. I found that the AFA, a virulently homophobic group, was financially supporting several LGBTQ-friendly United Methodist churches.

According to the site server logs, Will, read the aforementioned post for five minutes before accessing the contact page. Afterward, Will was served the front page of nine posts, but I have no idea if he read any of them. As far as posts about the AFA?? One post — that’s it. Keep that in mind when you read his email. (I sent Will a link to this post. Of course, he used a fake email address.)

Here’s what Will had to say. My response is indented and italicized.

Bruce,

It sounds like you don’t like the folks at AFA from your many derogatory adjectives.

Hmm.

Hmm, indeed. I re-read the eight year old article, looking for what you call “many derogatory adjectives.” You must have a very different definition of “many” from mine. I wrote that the AFA is: anti-abortion, anti-homosexual, anti-same-sex marriage, and anti-secular agenda. These are factual descriptions of the AMA, so I am perplexed as to why you think they are derogatory. If it walks, talks, and acts like a duck, it is a duck, and the AFA is a quacking duck if there ever was one. If you think these descriptions are wrong, please provide evidence for your claim. If not, I will assume you are just making shit up.

As far as “liking” the Wildmons and others who operate the American Family Association, no I don’t like them. I could say the same of any number of Evangelical preachers, churches, and parachurch organizations. I don’t like the St. Louis Cardinals either.

I suspect you are an AFA fanboy. I doubt that you “like” me. We all have likes and dislikes. Or are you one of those Christians who can only see the specks in the eyes of others and not the beam in your own? (Matthew 7:3)

Does that make you a “ good hater?”

I have no idea what you are talking about. Christians such as yourself are commanded to hate, and your deity is well known for his hatred. I, as a lowly, ignorant atheist, don’t hate people. I have no time for hate. I suspect that you, as many of my Evangelical critics, mistake pointed, forceful, direct critique as “hate.” That’s the problem with Evangelicals these days. Many of them are snowflakes, quickly butthurt and offended. If Evangelicals are going to drag their beliefs into the public square, then they should expect pushback. That’s how the Internet works.

You could have responded to my article, challenging my conclusions. Instead, you call me a “hater,” a claim for which you provided no evidence. You could have said all sorts of things to me, including sharing the Word of God with me or witnessing to me. Instead, you come off as yet another butthurt Christian, upset that I dared to talk out of school about the AFA and their money. Again, please point out where my article is factually wrong.

Live and do as you wish, but I’m always amazed at the hypocrisy folks like you express. You claim you’re diverse and honor diversity, but then you go through life attacking people different from you.

Again, you confuse “attack” with critique. If you want to see what “real” attack looks like, please read a few of the plethora of emails I have received from your fellow tribe members. Constant threats of Hell, death threats, attacks on my family, you name it, I have heard it from the followers of the Prince of Peace.

Please provide evidence for your claim that I “go through life attacking people different from me.”

Wow.

Wow, what, exactly? Your response to me is confusing. You read all of one post before contacting me; an investigatory article, not an opinion piece. Maybe I could understand your response if you had made a serious faith effort to read my writing, but you didn’t. Let me share with you a bit of advice from the Bible: Answering before listening is both stupid and rude. (Proverbs 18:13) I suggest you read the About page and the Why? page. Then you might be ready to judge my character.

Since you live in Ohio I imagine you go driving around and run Amish buggies off the road because they’re different from you.

Surely, Will, you are not this stupid. I have lived near Amish communities for much of my adult life. I pastored in southeast Ohio for eleven years. I had Amish-Mennonite neighbors, and their church was less than two miles away from my home. Our family attended numerous services at their church. I did business with them and had more than a few passionate theological discussions with them. They considered me their English friend.

Today, we live twenty minutes or so from a large Amish community. I admire their hard work agrarian lifestyle, and commitment to family. Yes, they are different from me, but I would never think of running one of their buggies off the road. I am surrounded by Evangelical Christians. I would never run their cars or trucks off the road either.

Bad analogy, Will, bad analogy, but let me run with it for a minute.

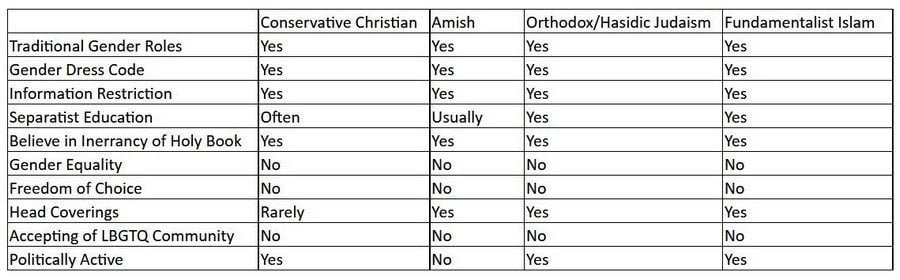

The Amish have never harmed me or my family in any way. They have never harmed my friends or acquaintances either. The Amish are the epitome of live and let live.

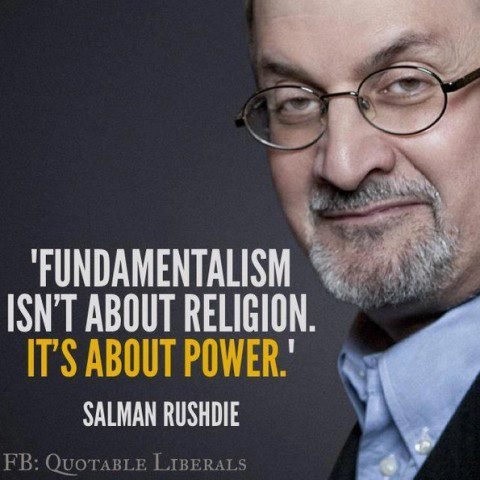

The AFA and Evangelicals by extension are nothing like the Amish. (Please see New Evangelical Term Used in the War Against Culture: A Canary in the Coal Mine.) Evangelicals are busy waging a zero-sum culture war against LGBTQ people, same-sex marriage, gender-affirming hormone therapy, gender reassignment surgery, abortion, reproductive rights, wokeness, books, birth control, sex education, evolution, socialism, humanism, and atheism. I am not talking about differences of opinion. Will, I wish you had expressed why you disagreed with me. Then, maybe, we could have had a discussion. Evangelicals have one goal in mind: theocracy. In their minds, the United States is a Christian nation (it’s not), and they intend to use the power of the state to establish Jesus as Lord and King and the Bible as the law of the land.

Evangelicalism is not a benign sect. Its teachings and practices have caused psychological and, at times, physical harm. This blog is a testimony to the fact that Evangelicalism can and does cause harm. The office waiting rooms of therapists are filled with clients harmed by Evangelical beliefs and practices. You don’t know this, of course, because the harm has been normalized for you. Until you break free from the bubble, you will never know how damaging life within the bubble really is.

If Evangelicals reach their theocratic goals, freedoms will be lost and people will die. Do you really think Evangelicals have the best interests of LGBTQ people at heart; that they have any intention of practicing “live and let live?” Not a chance.

No sir, you sir are the hater and you make it very publicly clear whom you hate.

I hope you realize by now that your judgment of me is incorrect; that you mistake passion for hate. Here’s a test for you. Please read Why I Hate Jesus. After you do, send me an email answering the question: who or what do I hate? Let’s see if you get it.

Saved by Reason,

Bruce Gerencser, 66, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 45 years. He and his wife have six grown children and thirteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Connect with me on social media:

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.

I look at all these groups and think, there’s no way I could live in one of those communities. After I graduated from high school, I did my best to escape the clutches of fundamentalist Christianity. Fortunately, I possessed a college degree from a highly ranked secular university and developed marketable skills, so I was able to support myself financially. Many in these communities, particularly women, are purposely raised without these skills, ensuring reliance on the community. It is my firm conviction that any group that purposefully restricts access to knowledge and education and discourages contact with outsiders is inherently harmful and potentially abusive. Those in power may thrive within these systems, but the systems themselves are designed to benefit those in power at the expense of the powerless.

I look at all these groups and think, there’s no way I could live in one of those communities. After I graduated from high school, I did my best to escape the clutches of fundamentalist Christianity. Fortunately, I possessed a college degree from a highly ranked secular university and developed marketable skills, so I was able to support myself financially. Many in these communities, particularly women, are purposely raised without these skills, ensuring reliance on the community. It is my firm conviction that any group that purposefully restricts access to knowledge and education and discourages contact with outsiders is inherently harmful and potentially abusive. Those in power may thrive within these systems, but the systems themselves are designed to benefit those in power at the expense of the powerless.