People who suffer with chronic illnesses are often accused of giving up or giving in. Irrational hyper-optimism has so infected the American psyche, that those who embrace their lives as they are often are looked down upon. Put mind over matter; never give in; be pro-active, always hope for a better tomorrow; these and other cheap clichés are often recited to the chronically ill, implying that their illnesses are somehow their own fault. If they would just take this drug, have this treatment, or see this doctor, then all would be well. An unwillingness to do these things is often viewed as laziness or giving in. Often, people take their own experiences and project them onto others, thinking that their outcomes would be the same for everyone if they would just follow the same course of treatment. People who think in this manner can often oppress and hurt chronic-illness sufferers, even when they don’t intend to do so. A recent health-related dust-up on social media has left me wondering if I should continue to write about my health problems and my battle with chronic pain. While I find writing about these things to be psychologically and physically helpful, sometimes the responses from readers can undo any of the health benefits gained from the writing.

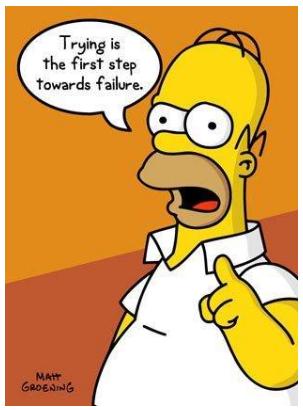

I’ve repeatedly been told that I need to keep trying; that it is better to try and fail than not try at all. While I am sure people who say this to me mean well, I wonder if they have ever considered how such cheerleading can actually hurt those who are struggling just to make it to another day. I was diagnosed with Fibromyalgia 18 years ago. Since then, the laundry list of health problems I have has continued to grow. No matter how many doctors I see, how many tests I have, or how many different drugs I try, I still wake up every morning in pain. I know that there is no cure on the horizon. No magic potion is going to undo the damage done by two decades of fighting with the medical equivalent Mohammed Ali.

I have moments when I pretend that I can ignore my body and do what I want. Thanks to a decade of medical treatment, we are swimming in medical debt. Because of changes in our medical insurance, twenty-five to thirty percent of our income is spent on medical bills — mostly mine. I find it almost unbearable to watch Polly walk out the door every day, knowing that 25% of that day’s earnings will go towards my medical expenses.

Recently, I once again ignored reality and decided that I would get a job so I could help pay the medical bills. I need employment that will allow me to sit while I work and take frequent breaks. Showing up for an interview in a wheelchair or haltingly walking with a cane usually results in the interviewer telling me, thanks for applying. We will keep your application on file. So, as I did recently with an interview with Meijer, I pretended that I am not a cripple. And just like that they offered me a job. Would they have offered me the job if I was in a wheelchair or walk with a cane? I doubt it. I’m sure if I told them that I have arthritis of the spine and can only stand for 15 or so minutes at a time, they would have politely told me that they had no job for me. Yes, the law says employers must accommodate the handicapped, but in the real world a 60-year-old cripple has little chance of winning a job over a healthy 25-year-old. Discrimination against the handicapped and older prospective employees happens without employers ever saying a word. I try to remember back when I was young man responsible for hiring employees for the various companies I worked for. Young and able-bodied were always preferable to old and crippled. In the case of Meijer, they are so desperate for workers, that they were willing to hire a broken-down old man such as I. As my orientation day drew near, Polly and I had a heart-to-heart talk about whether I could really do this job. Mentally, I told myself, sure, I can do this. But, knowing that I can’t stand for longer than 15 minutes at a time means that it’s impossible for me to work the floor or run a cash register at Meijer. Polly, who knows better than anyone (including myself) what I can and can’t do finally persuaded me to not take the job. As is often the case when it comes to my health, she has a lot more sense than I do. I can deceive myself into thinking that I can do something, when Polly knows I can’t. This is not me giving up or giving in as much as it is accepting things as they are.

After turning down Meijer, I decided to try my hand at a work-from-home job with Amazon. I entered training with grand ambition, thinking that I had finally found something that I could do. Amazon’s training was quite extensive and grueling, yet I passed all the exams and was in the top five percent of my class of 650. Based on several conference calls with other new hires and management, I determined I was by far the oldest man in my group. Most of the new hires were in their twenties and thirties, as were many of the members of management.

Encouraged by Polly and my counselor, I continued to slog through the training even though I was worried about remembering everything I had learned. Both of them told me they were sure I could do the job. After completing the training, I was deemed a newly-minted customer service representative — ready to start taking live calls. I thought, I know I can do this. A part of me knew better, but all I could think of was our increasing debt, so I pushed my better judgment aside and answered my first call. The call started well — a man wanting to know why his order hadn’t been delivered — and then what I feared would happen, did. I couldn’t remember what I needed to do next. My mind literally froze — covered with a pain-laden, fatigued cloud. The customer became frustrated with me and hung up. After emotionally regrouping from my failure, I took another call only to have continued cognitive problems. I could not remember what I needed to do. This customer, instead of hanging up on me started screaming, so much so that I hung up on her. After this call, I mentally collapsed, knowing that I was unable to do what the job required. Several days later, Amazon and I agreed that it was best if I resigned, and so I did.

The Amazon catastrophe has caused great psychological damage and pain. Pushed to the very edge of the abyss, my thoughts turned to suicide. While the suicidal thoughts faded after a couple of days, the assault on my mind remains the same. It’s hard not to feel worthless, that I am little more than a burden on my wife and family. They will certainly tell me that I am not, but it’s hard not to think that I am. This is usually the point where well-meaning people interject one of their cheap clichés about making lemonade when life gives you lemons. I am always polite when people say one of their Oprah-like maxims, but there are days when I want to tell them, until you’ve walked in my shoes, shut the fuck up.

If you’ve noticed in recent months that the volume of my writing has diminished, now you know why. Things are better than they were a month ago, but I’m far from being ready to tackle another job opportunity. I do have thoughts of trying to make some money using my photography skills. In particular, I am considering starting a real estate photography business. Several of my children have recently bought homes, and the common denominator with all the homes they looked at was that the property photographs were terrible. I mean a-w-f-u-l. I plan to send out letters to local realtors offering to do their property photography. Several years ago, I applied for such a job with a local realtor only to be told by her that I was so overqualified that she didn’t believe I would keep the job for long. I tried to explain to her that she need not worry about that, but her mind was made up.

I hope this new business venture will prove to be viable and profitable. If it’s not, we will be forced to make some serious cuts in our budget. Hoping for a better day doesn’t change the fact that there are bills to pay. It used to be that it was easy to work out payment plans for medical debt, but now the physicians group my doctors are a part of will only make a payment arrangements for up to 12 months. After that, they demand you borrow the money to pay the debt. Last year, we had to borrow $5,000 to pay for my previous round of tests and procedures. While I’m not ready to throw in the towel, the daily pressure of these things makes it hard to focus on a better tomorrow. For those who have walked a similar path, you know what I’m talking about.

[signoff]