A commenter on this blog, T34, recently asked the following question on the post titled, Is Christianity a Blood Cult?

I read a few of the articles [on this blog] and none of the titles seem to answer my question. Please know I [am]not an evangelist. I honestly am searching for answers. I want to know if Bruce has had any supernatural or spiritual (not religious) experiences or relationship with God or another? I would like to understand more why Bruce chose to be an outright atheist as opposed to just non-religious or agnostic. And if he has had any supernatural or spiritual experiences I’d like to know what they were and what he thinks of them now.

Polly and I typically listen to The Atheist Experience on Sunday nights before we go to bed. This week, Matt Dillahunty, one the hosts, mentioned the difficulty in defining the word “spiritual” or “spirituality.” Ask a hundred people to define these words and you will get 101 different answers. “Spiritual” to a Baptist is very different from the way a Catholic, Buddhist, Pagan, or humanist might define the word. T34 equates “spiritual” with “supernatural,” so I will proceed using that definition, understanding that there is no absolute textbook definition for these words. For example, a Charismatic Christian considers speaking in tongues to be “supernatural” experience. An Independent Fundamentalist Baptist (IFB) Christian, however, considers speaking in tongues a tool used by Satan to lead people astray.

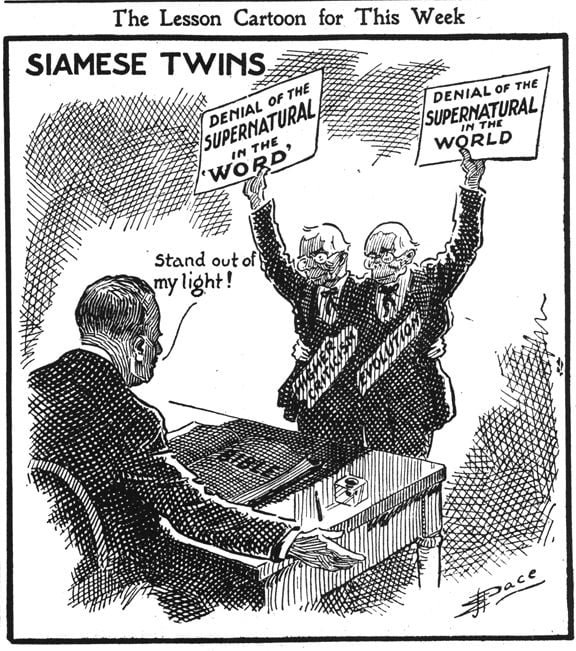

Before I answer T34’s question, I do want to answer one claim that she makes: she suggests that supernatural and spiritual experiences are not religious. I don’t believe that at all. It is religion, in all its shapes and forms — organized or not — that gives life to supernatural and spiritual claims. Without religion, I doubt humans would have much need for such experiences.

My editor pointed out that non-religious people can and do have paranormal experiences. Are paranormal experiences such as “seeing” ghosts supernatural in nature? Maybe, but I suspect that if naturalism and science had a stronger hold on our thinking, thoughts of ghosts would likely fade away. I’m deliberately painting with a BWAPB — Bruce’s Wide Ass Paint Brush. I recognize that there could be some experiences that might not fit in the box I have constructed in this post. Unlikely, but possible.

I had a church piano player in Somerset who was certain that her dead lover (long story) appeared next to her when she played the piano. I never saw him, but she swore he was right there cheering her on as she played “Victory in Jesus.” Could her story be true? Sure, but not in the way some people may think it is. Her story is true in the sense that she “thinks” it is. In her mind, this man is very real, even though his dead body is planted in the nearby cemetery. Thus such things can be “true” without actually being factually and rationally true.

I was part of the Christian church for 50 years. While I spent my preschool years in Lutheran and Episcopal churches, once I started first grade in 1963, I attended Independent Fundamentalist Baptist (IFB), Southern Baptist, and garden variety Evangelical churches. I spent 25 years pastoring Evangelical churches in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan, pastoring my last church in 2003.

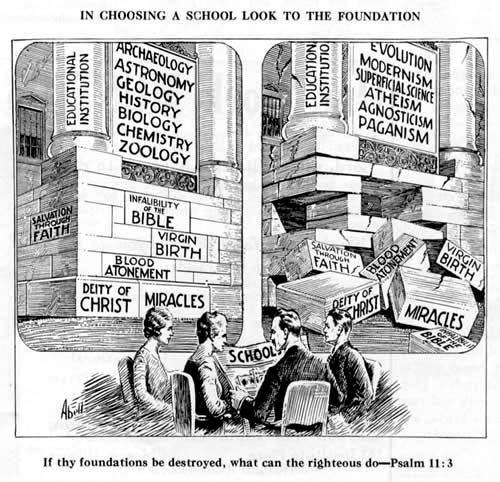

When I discuss the spiritual/supernatural experiences I have experienced in my life, these events must be understood in light of the sects I was raised in, what my pastors taught me, what I learned in Bible college, and my personal learning and observations as a Christian and as an Evangelical pastor. My understanding of what is spiritual/supernatural is socially, culturally, tribally, and environmentally conditioned. A Southern Baptist church can be located on the northwest corner of Main and High in Anywhere, Ohio and a Pentecostal church located on the southeast corner of Main and High in the same town. Both preach Jesus as the virgin-born son of God, who came to earth, lived a sinless life, and died on the cross for our sins. Both preach that all of us are sinners in need of salvation, that one must be born again to inherit the Kingdom of God. And both believe Satan is real, Hell is sure, and Donald Trump is the great white hope. Yet, when it comes to “experiencing” God, these churches wildly diverge from one another. The Pentecostals consider the Baptists dead and lifeless, lacking Holy Ghost power, while the Baptists consider their Pentecostal neighbors to be way too emotional, to have a screw loose. Both churches “experience” God in their own way, following in the footsteps of their parents, grandparents, and older saints who have come before them.

As a man who pastored several churches in desperate need of change, I heard on more than a few occasions church leaders and congregants say, when confronted with doing something new or different, “That’s not the way we do it!” Behaviors become deeply ingrained among Christian church members. Our forefathers did it this way, we do it this way, and we expect our children and grandchildren will do the same. A popular song in many Evangelical churches is the hymn, “I Shall Not be Moved.” The chorus says:

I shall not be, I shall not be moved.

I shall not be, I shall not be moved;

like a tree planted by the water,

I shall not be moved.

That chorus pretty well explains most churches. Whatever their beliefs and practices are, they “shall not be moved.” So it is when determining what are real “spiritual” or “supernatural” experiences.

As a Baptist, I believed the moment I was saved/born-again, that God, in the person of the Holy Spirit, came into my “heart” and lived inside of me, teaching me everything that pertains to life and godliness. It was the Holy Spirit who was my teacher and guide. It was the Holy Spirit who taught me the “truth.” It was the Holy Spirit who convicted me of sin. It was the Holy Spirit (God) who heard and answered my prayers. It was the Holy Spirit who directed every aspect of my life.

As a pastor, I typically preached a minimum of 4 sermons a week. I spent several full days a week — typically 20 hours a week — reading and studying the Biblical text, commentaries, and other theological tomes. As I put my sermons together, I sought God’s help to construct them in such a way that people would hear and understand what I had to say. Daily, I asked God to fill me with his presence and power, especially when I entered the pulpit to preach. I always spent time confessing my sins before preaching, believing it was vitally important for me to “right” with God before I stood before my church and said, “thus saith the Lord.”

I expected the Holy Spirit to take my words and use them to work supernaturally among those under the sound of my voice. I believed that it was God alone who could save sinners, convict believers of their sin, or bring “revival” to our church. I saw myself as helpless — without me, ye can do nothing, the Bible says — without the supernatural indwelling and empowerment of the Holy Spirit.

As a committed Christian, I was a frequent pray-er. I prayed for all sorts of things, from the trivial to things beyond human ability and comprehension. I believed that with God all things were possible. In the moment, I believed that God, through the work of the third part of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit, was working supernaturally in my life, that of my family, and of my church. My whole life was a “spiritual” experience, of sorts. God was always with me, no matter where I went, what I said, or what I did, so how could it have been otherwise?

In November 2008, God, the Holy Spirit, along with all of his baggage, was expelled from my life. For the past twelve years, I have taken the broom of reason, science, skepticism, and intellectual inquiry and swept the Christian God from every corner of my mind. While I wish I could say that that my mind is swept clean of God, dust-devils remain, lurking in the deep corners and crevasses of my mind. All I know to do is keep sweeping until I can no longer see “God” lurking in the shadows.

T34 wants to know how I now view the “spiritual” and “supernatural” experiences from my past life as a Christian and Evangelical pastor. As an atheist, I know that these experiences were not, in any way, connected to God. I have concluded that the Christian God is a myth, that he/she/it is of human origin. If there is no God, then how do I “explain” the God moments I experienced in my life? Does Bruce, the atheist, have an explanation for what “God” did in his life for almost 50 years?

Sure. The answer to this question is really not that difficult. I spent decades being indoctrinated by my parents, pastors, and professors in what they deemed was the “faith once delivered to the saints.” This indoctrination guaranteed the trajectory of my life, from a little redheaded boy who said he wanted to be a preacher when he grew up — not a baseball player, policeman, or trash truck driver, but a preacher — to a Bible college-trained man of God who pastored seven churches over 25 years in the ministry. I couldn’t have been anything other than a pastor.

And so it is with the “spiritual” and “supernatural” experiences I had in my life. My parents, churches, pastors, and professors modeled certain beliefs and practices to me. I “experienced” God the very same way these people did. Social and tribal conditioning determined how I would “experience” God, not God himself. He doesn’t exist, remember?

I sincerely believed that, at the time, God was speaking to me, God was leading me, and God was supernaturally working in and through my life. But just because I believed these things to be true, doesn’t mean they were. A better understanding of science has forced me to see that my past life was built upon a lie, a well-intended con. This is tough for me to admit. In doing so, I am admitting that much of my life was a waste of time. Sure, I did a lot of good for other people, but the “spiritual” and “supernatural” stuff? Nonsense. Nothing, but nonsense. And saying this, even today, is hard for me to do. It’s difficult and painful for me to admit that I wasted so much of my life in the pursuit of something that does not exist.

T34 asked why I “chose to be an outright atheist as opposed to just non-religious or agnostic.” I am not sure what an “outright” atheist is as opposed to an atheist. Remembering what I said about the connection between religion and the “spiritual” and “supernatural,” isn’t someone who is non-religious an atheist or an agnostic? While such people may not carry such labels, aren’t non-religious people those who do not believe in deities? If someone believes in a God of some sort, be it a personal deity or some sort of divine energy, they can’t properly, from my perspective, be considered non-religious.

Granted, there is a difference between people who are non-religious and people who are indifferent towards religion. An increasing number of Americans are indifferent towards religion. They simply don’t give a shit about religion, be it organized or not. I suspect that many of these NONES will eventually become agnostics and/or atheists.

I label myself this way:

I am agnostic on the God question. I am convinced that the extant deities are no gods at all; that the Abrahamic God is a human construct. That said, I cannot know for certain whether, in the future, a deity might make itself known to us. I consider the probability of this happening to be .00000000000000000000001. Thus, I live my day-to-day life as an atheist — as if no deity exists. I see no evidence for the existence of any God, be it Jehovah, Jesus, Allah, Vishnu, or a cast of thousands of other gods. The only time I “think” about God is when I am writing for this blog. Outside of my writing, I live a God-free life, as do my wife, dog, and cat.

Bruce Gerencser, 66, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 45 years. He and his wife have six grown children and thirteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Connect with me on social media:

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.