All of us at the Freedom From Religion Foundation fall somewhere between being fearful and constantly mindful that a disgruntled maniac with an assault weapon could come into our office building and murder us. In our line of work we regularly come up against angry religious extremists who wish death upon us and all others who advocate for the constitutional separation of religion and government. As the recent lone gunman in Las Vegas—who singlehandedly murdered more than 50 people and injured hundreds more—has reminded us, in the United States this type of mass shooting is far more common than it needs to be.

Believe it or not, as a constitutional issue this debate has a lot in common with the attempts to redefine religious freedom.

Data that predates the shootings in Orlando and Las Vegas shows that the United States is home to more mass shooting events than any other country. With only 5 percent of the world’s population, we were home to 31 percent of all mass shootings between 1966 and 2012. And the rate of mass shootings in our country has tripled since 2011, even as the overall rate of gun violence has declined.

There is compelling evidence suggesting that common-sense gun control laws would go a long way toward preventing mass shooting events in the United States. They worked in Australia, which passed a law to remove semi-automatic weapons from civilian possession in 1996, after 35 people died in a mass shooting in Tasmania. In the 18 years before the gun law reforms, there were 13 mass shootings in Australia. In the 11 years after? None. Australia has also enjoyed an accelerated decline in firearm homicides over that same period.

While one could quibble about how best to interpret the complex data coming out of Australia—and gun lobbyists do—the more fundamental question is: “Why not try this in the United States?” Why won’t Congress take steps to ban the sale of assault-style weapons—a step that could dramatically reduce the number of mass shootings? What are the “cons?” Why, instead, do politicians limit themselves to tweeting out their “thoughts and prayers” while taking no action?

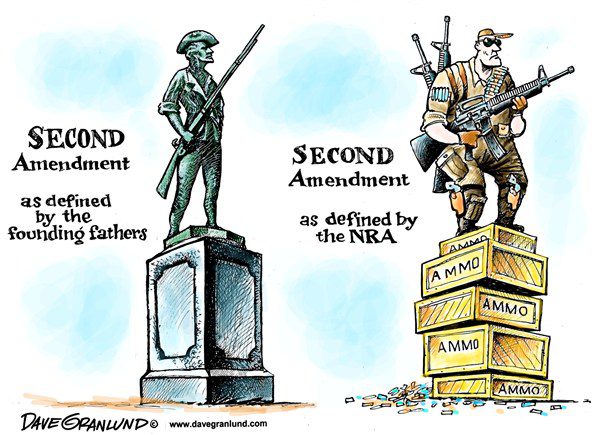

The answer to these questions lies in how the “gun rights” lobby has pushed a particular view of the Second Amendment. That transformation is the reason FFRF is talking about this, the reason it’s relevant to state-church separation. “Religious freedom” advocates are currently trying to do to the First Amendment what the gun lobby did to the Second.

In 1977, the National Rifle Association experienced the “Revolt in Cincinnati,” where extreme gun rights advocates took over the NRA and converted it from an organization that primarily advocated for firearm safety education, marksmanship training and recreational shooting into a lobbying powerhouse focused nearly exclusively on Second Amendment advocacy. One excellent summary of this transformation includes this note: “The NRA’s new leadership was dramatic, dogmatic and overtly ideological. For the first time, the organization formally embraced the idea that the sacred Second Amendment was at the heart of its concerns.” Sound familiar?

Since the Revolt in Cincinnati, the gun rights lobby has successfully pushed an absolute right to gun ownership in courts and legislatures, culminating in the 2008 Supreme Court decision District of Columbia v. Heller, which established for the first time a dramatic reimagining of the Second Amendment as creating an individual right to own a gun. This dramatic reimagining is exactly what groups like Liberty Institute are trying to do with the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause. They are trying to turn free exercise into an absolute right that must be protected even when it infringes on the rights of others.

To hear those seeking to redefine religious freedom tell it, any action motivated by religion is permissible, no matter what its impact. If they deny an LGBTQ citizen a cake because of sexual orientation, that’s their god-given right. Logically, that means they could deny atheists, Jews or even discriminate on the basis of race, though they would be unlikely to say so out loud.

People can believe whatever they like. They are free to believe the voices they’re hearing are God, that thetans and evil spirits make us sad, or that the Earth is only a few thousand years old. But the right to act on those beliefs is by no means absolute. This is best illustrated with the example that the Supreme Court used more than 130 years ago: human sacrifice.

Hearing a command for human sacrifice is fairly common in the bible and the story of Abraham almost sacrificing his son Isaac is often held up as a measuring stick for how deep one’s faith should be. But people who, like Abraham, hear God ordering them to kill their children do not have a right to do so. Once someone is committing murder, religious freedom is irrelevant.

Somewhere on the spectrum of religiously motivated action, civil law can step in. That line should be drawn where the rights of others begin. As Thomas Jefferson put it, “The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” But if religion mandates picking pockets and breaking legs, it comes under the purview of our secular law. And no belief, no matter how fervent, should change that.

Second Amendment rights are not absolute: You can’t bring your gun on a plane or into a school, felons can’t own them, and some states regulate concealed carry or unlicensed gun sales. (Incidentally, the states that regulate guns more strictly have lower incidents of gun-related homicides.) The reason common-sense, data-driven gun laws cannot make it through Congress is because the idea that Second Amendment rights are absolute has been deliberately foisted on American legislatures and courts.

“Religious freedom” advocates are working to achieve the same sleight of hand with the First Amendment and their claimed right to act on their religious beliefs. It began with the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, made a huge gain with the Hobby Lobby case, and is set to be decided by the Supreme Court in Masterpiece Cakeshop very soon.

The absolutist view of the Second Amendment is killing Americans. To adopt that same absolutist view for the Free Exercise Clause “would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and, in effect, to permit every citizen to become a law unto himself. Government could exist only in name under such circumstances,” as the Supreme Court wrote in 1879.

There is no constitutional right to act out one’s religious beliefs in a manner that infringes on others’ rights, including the right to equal protection under the law. Discrimination in the name of religion is still discrimination. We cannot accept an absolutist interpretation of the Constitution. Instead, we must look at how the First and Second Amendments are being used—and abused—to amass power and to achieve results that range from nonsensical to lethal. (And yes, an absolutist view of the Free Exercise of religion will lead to lethal consequences too).

The political nonresponse to mass shootings in this country has become a tragic pattern, ripe for parody. We cannot continue to accept inaction based on a vague appeal to an absolute constitutional right. At the Freedom From Religion Foundation, we fight every day against political overreach by “religious freedom” advocates, who cloak their discrimination in constitutional language. We must reject their attempts to take a page from the NRA playbook by foisting an absolutist reimagining of the Free Exercise Clause onto the legal landscape. The right to act out one’s religious beliefs must end where the rights of others begins.

— Sam Grover and Andrew L. Seidel, Constitutional Attorneys, Freedom From Religion Foundation, Gun Control and Religious Freedom: How Thinking in Constitutional Absolutes is Killing People