Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

— U.S. Constitution, First Amendment

Central to our way of life in the United States is the First Amendment of the Constitution: freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of peaceable assembly, and freedom to petition the Government for redress of grievances.

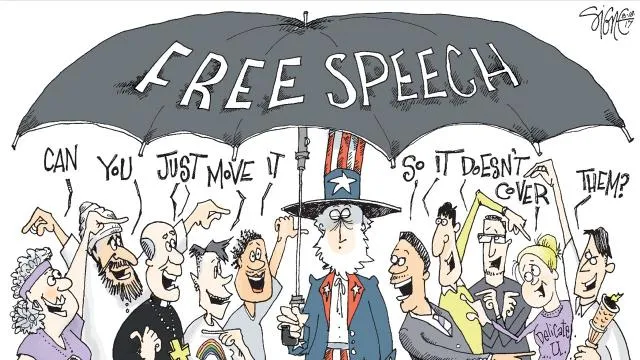

In this post, I want to briefly talk about freedom of speech (or expression).

The Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts’ website defines and explains free speech this way:

Among other cherished values, the First Amendment protects freedom of speech. The U.S. Supreme Court often has struggled to determine what exactly constitutes protected speech. The following are examples of speech, both direct (words) and symbolic (actions), that the Court has decided are either entitled to First Amendment protections, or not.

The First Amendment states, in relevant part, that:

“Congress shall make no law…abridging freedom of speech.”

Freedom of speech includes the right:

- Not to speak (specifically, the right not to salute the flag). West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943).

- Of students to wear black armbands to school to protest a war (“Students do not shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate.”). Tinker v. Des Moines, 393 U.S. 503 (1969).

- To use certain offensive words and phrases to convey political messages. Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971).

- To contribute money (under certain circumstances) to political campaigns. Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976).

- To advertise commercial products and professional services (with some restrictions). Virginia Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Consumer Council, 425 U.S. 748 (1976); Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 433 U.S. 350 (1977).

- To engage in symbolic speech, (e.g., burning the flag in protest). Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989); United States v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310 (1990).

Freedom of speech does not include the right:

- To incite imminent lawless action. Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969).

- To make or distribute obscene materials. Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957).

- To burn draft cards as an anti-war protest. United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968).

- To permit students to print articles in a school newspaper over the objections of the school administration. Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260 (1988).

- Of students to make an obscene speech at a school-sponsored event. Bethel School District #43 v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986).

- Of students to advocate illegal drug use at a school-sponsored event. Morse v. Frederick, 551 — U.S. — 398 (2007).

What about “hate” speech? Iowa State University answers the questions, “What is hate speech?” and “Is hate speech protected by the First Amendment?”:

The term “hate speech” is often misunderstood. “Hate speech” doesn’t have a legal definition under U.S. law, just as there is no legal definition for lewd speech, rude speech, unpatriotic speech, or other similar types of speech or expression that people might condemn. The term often refers to speech or expression that the listener believes denigrates, vilifies, humiliates, or demeans a person or persons on the basis of membership or perceived membership in a social group identified by attributes such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or other protected status. Speech identified as hate speech may involve epithets and slurs, statements that promote malicious stereotypes, and speech denigrating or vilifying specific groups. Hate speech may also include nonverbal depictions and symbols.

In the United States, hate speech receives substantial protection under the First Amendment, based upon the idea that it is not the proper role of the government to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive. Instead, the government’s role is to broadly protect individuals’ freedom of speech in an effort to allow for the expression of unpopular and countervailing opinion and encourage robust debate on matters of public concern even when such debate devolves into offensive or hateful speech that causes others to feel grief, anger, or fear.

….

However, it goes without saying that just because there is a First Amendment right to say something, doesn’t mean it should be said.

….

The First Amendment does not protect illegal conduct just because that conduct is motivated by an individual’s beliefs or opinions. Therefore, even though hate speech is protected by the First Amendment, illegal conduct motivated by an individual’s hate for a particular protected group may be regulated by local, state, or federal law, and / or university policies. These laws are sometimes identified as “hate crimes.”

It is important to understand that the First Amendment restricts government from regulating speech (expression), though there are exceptions. The First Amendment does not apply to speech restrictions enacted by businesses and private citizens. Over the years, countless Evangelicals have said that I am violating their right to free speech by not letting them say whatever they want on this site. However, this blog is not connected with the government in any way. It is owned and operated by a private citizen: me. No one has the right to comment on this site unless I permit them to do so.

As a writer, I have the right to say what I want, regardless of whether people agree with me. We do have civil slander and defamation laws, but the bar is high for the prosecution of such offenses. Just because someone says something about you that you don’t like doesn’t mean he is slandering you.

The Ohio Bar has this to say about defamation:

Yes. Individuals, not just the media, can be held liable for defamation if they either publish (libel) or say (slander) something about someone that isn’t true and that person suffers harm as a result. If you defame a private individual, that person would have to be able to prove: 1) that you made a statement, reported as fact, to another person; 2) that the statement was false; 3) that the statement caused damage to that person; and 4) that you were negligent in making that statement. If you defame a public figure (such as a celebrity or member of government, for example), that person will have to prove: 1) that you made a statement to another person, reported as fact; 2) that the statement was false and caused damage; and 3) that you made the statement with actual malice-that is, with knowledge that the statement was false or with reckless disregard as to whether the statement was false or not.

Remember, however, that you cannot be held liable for voicing your opinion, only for making untrue factual assertions.

Sadly, many people think they have a constitutional right not to be offended. This, however, is not true.

In 2022, Michael Bruce wrote:

Our right to be offensive is increasingly being seen as this pesky, little symptom of the First Amendment that must be either begrudgingly entertained or reluctantly accepted. People will casually write off being offensive as uncouth or unbecoming of a civilized society; they are, however, mistaken. The ones who are annoyed by our right to be offensive are the same ones who are likely to be ignorant of the fact that we are where we are today as result of individuals offending the orthodoxies of their day. They are also likely unaware of the consequences that limiting offensiveness can have.

One might ask themselves whether it’s worth being offensive in today’s era of wokeism, microaggressions, and cancel culture. The answer should be (and always will be) a resounding and resolute yes. Below are three reasons why we must embrace, and continue, our tradition of being offensive.

First, we owe it to all of those who came before us and who sacrificed so much in the name of giving offense. We owe it to those who were mocked and ridiculed, booed and hissed at, beaten or imprisoned, exiled and ostracized, and hanged or burned at the stake all for simply offending the doctrines and dogmas of their day. Literal blood, sweat, and tears were given by countless generations so we could be where we are today.

Secondly, giving offense has been the main driver of change over (at least) the last millennium. As pointed out above, our society has gotten to the point it is at today because individuals thumbed their noses at the norms and orthodoxies of their day.

….

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, it is imperative that we continue our long tradition of offending contemporary orthodoxies because the only other alternative is clamping down or dismissing speech and expressions that are deemed offensive. The notion that any idea that is legitimately expressed can be silenced or banned on the grounds that it is merely “offensive” is censorship, and as one of our greatest founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin, put it, “Censorship is the handmaiden to tyranny.” So, if you are against tyranny, you have to be for offensiveness.

As was stated at the start, the right to be offensive, which has been affirmed to us as citizens by various Supreme Court cases (RAV v. St. Paul, Texas v. Johnson, Snyder v. Phelps) is increasingly being portrayed as a thorn in the side of modern society; as if the only thing stopping us from achieving an idyllic society is our individual right to give offense. It is time that that misconception comes to an end and we start to view this inalienable right for what it really is: the heart and soul of the First Amendment.

British writer Charles Hymas wrote earlier this year:

No religion has a right to be exempt from criticism, the security minister has said ahead of a crackdown on extremism.

Tom Tugendhat said no faith had a right not to be challenged amid concerns that some extremists have used intimidation and threats of violence against those perceived to have insulted Islam.

It follows the case of a teacher in Batley, West Yorks, who received death threats after showing pupils a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed during a religious education lesson almost two years ago and has remained in hiding ever since as he fears for his life.

Mr Tugendhat declined to comment on individual cases but he said: “There is absolutely no right for any religion to be offended, if we accepted that then we’d still be Catholic.

“Every religion has the right to be challenged and there is no religion that has the right to be immune from that for any reason at all.”

Speaking on GB News, he added: “Anybody can challenge any article of any faith, it is absolutely fundamental, and there is no right to be immune from that.

“You know very well, because it’s the fundamental tenet of your job as a journalist to have freedom of speech.”

I primarily write about religion (particularly Evangelical Christianity) and politics — two subjects never spoken of in polite company. I know my writing offends some people, but that doesn’t mean I must stop doing so. The offended are free to respond in the comment section (as long as they abide by this site’s comment policy), send me an email or social media message, write a blog post or news article in response to my offensive writing, write a letter to the editor of the local newspaper decrying my writing, or any other constitutionally protected, legal action. The offended have numerous tools at their disposal to rebut my writing. They don’t, however, have any legal grounds to force me to remove something I have written from this site.

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.