I grew up in a poor home, one that, at times, vacillated between dirt-poor and existence-threatening poverty. Up until I was fifteen, Dad always worked, be it as a salesman or a local truck driver. Mom, on occasion, would work, but her severe mental health problems precluded her from maintaining steady employment. Mom and Dad divorced in the spring of my ninth-grade year. Mom tried to go back to work, but eventually gave up and signed up for ADC — aid for dependent children. From that point forward, we were a welfare family.

While my siblings and I were in school, the State of Ohio provided Medicaid coverage for us. Medicaid covered medical, dental, and eye care. I have many stories I could share (and shall over time) about being on welfare, complete with the embarrassment of being refused medical/dental care and being shamed for using food stamps, but today I want to share a story about getting my first pair of glasses.

In the spring/summer of 1971, I played baseball for Jacques Sporting Goods in Findlay, Ohio. I was never a great player. Now that I was playing with and against kids who played for local high school teams, my lack of hitting skill was quickly exposed. I was, however, lefthanded and a fast runner. I suspect it was for these reasons that I made the team — barely. I was the kid at the far end of the bench, a player or two ahead of the water boy. Good enough to play, but not the kid you wanted at the plate when the game was on the line.

Typically, practices were held at Rawson Park, located on Broad Ave. One day, I was fielding flies in right field. I was having an awful time seeing and catching the ball. After more than a bit of grief over my horrible fielding, my coach suggested that I get my eyes checked. Sure enough, I needed glasses.

Mom made me an appointment to see an optician that took Medicaid insurance. After checking my eyes and determining I was nearsighted, the welfare box was brought out for me to choose a pair of frames. No wireframes. No stylish frames. Just frames that screamed to everyone you went to school with that you were poor and on welfare.

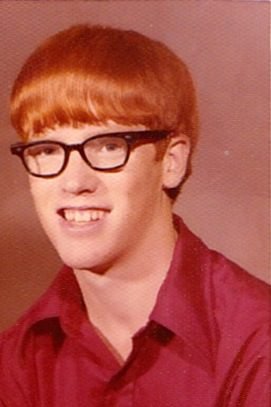

As you can see from my ninth-grade school photo, my black cheap plastic framed old-man’s glasses didn’t go with my complexion and bright red hair. I was so embarrassed, but what could I do? My vision was such that I needed glasses to do my school work, and more importantly, play baseball.

After being endlessly ridiculed over my welfare glasses for several weeks, I decided to hustle up enough money for me to buy an age-appropriate pair of fashionable wirerimmed glasses. This put an end to me being a poster child for “welfare.”

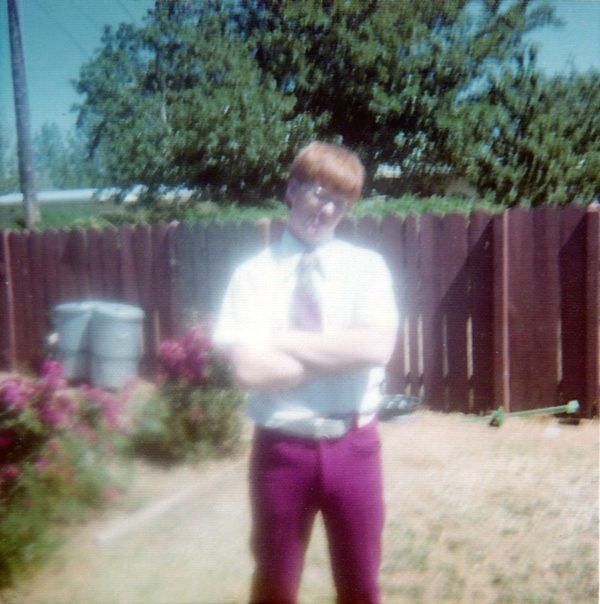

The picture of me above, taken in Arizona, shows me with my wirerimmed glasses (and my white belt, burgundy polyester pants, and white shoes — which you cannot see). In the first picture, I stood out, for all the wrong reasons. High school was brutal enough without painting a metaphorical target on my body. Thanks to me playing baseball and basketball, I wasn’t treated as harshly as other welfare kids, but I did receive enough ill treatment to remind me that I wasn’t part of the in-crowd (my Fundamentalist religious beliefs and practices didn’t help either). As I write this post, my mind goes back to the experiences of several of my fellow poor classmates. They didn’t have sports to give them a bit of respectability. They were daily bullied and marginalized, routinely preyed on by entitled “rich” kids.

Fast forward to 2022. Families on welfare have a hard time finding medical/dental/eye care. Currently, families need to drive 30-60 miles for dental care. There is a local “welfare” clinic in Bryan, but clients often must wait weeks and months to see a dentist. Try telling Johnny with a throbbing tooth that he has to wait a month to see a dentist. Such lack of access, in my opinion, is immoral.

Several days ago, Polly told me a story about one of her fellow employee’s recent experience getting glasses for her young son. The children have Medicaid insurance coverage. After the eye doctor determined the boy needed glasses, it was time to choose a pair of frames. Out came the dusty “welfare” box with its spartan selection of cheap, plastic glasses. Fifty years after my eyeglass experience, nothing has changed. Opticians could provide better, more stylish frames, but they don’t. Why should they, right? If the state of Ohio wants poor children to have stylish frames, it should pay providers more. Fair enough, but opticians could provide nicer frames for patients on Medicaid. Sure, it might cost them a few bucks, but thanks to frames now being sold (cheaply) online, we now know that eyeglass providers have been making a killing for years. (We buy our glasses and prescription sunglasses from Zenni Optical, saving hundreds of dollars, all without sacrificing quality.)

The young boy in question dutifully chose his welfare glasses. Fortunately, his mother also had eyecare insurance from work. This allowed her to choose a stylish pair of glasses for her son. Of course, she had to pay money for the nicer glasses. Can I scream now? Mom did the right thing for her son. Not that many years removed from high school, she knows how students can treat those who look different or are wearing the scarlet W on their faces.

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.