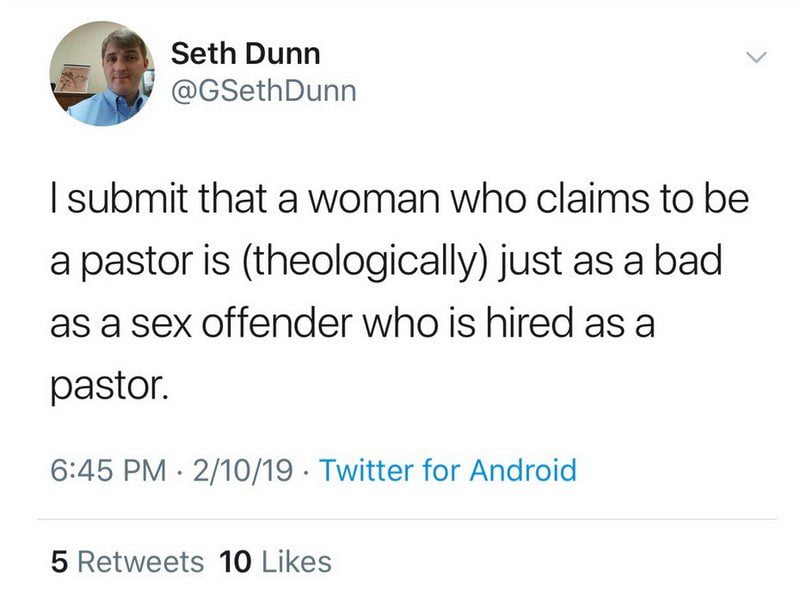

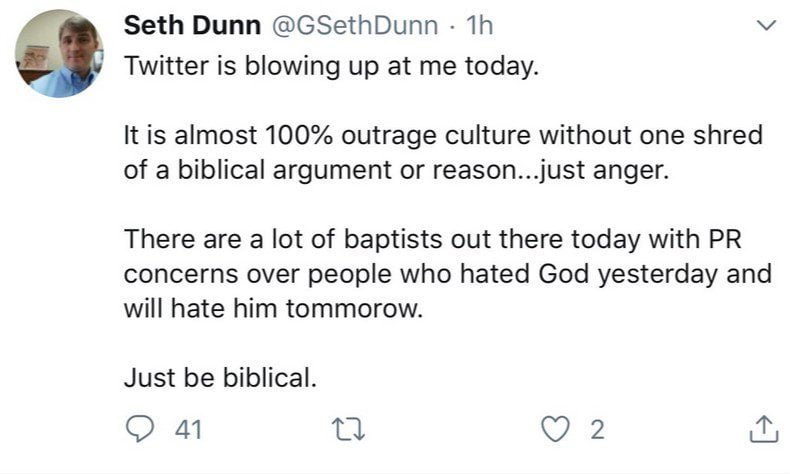

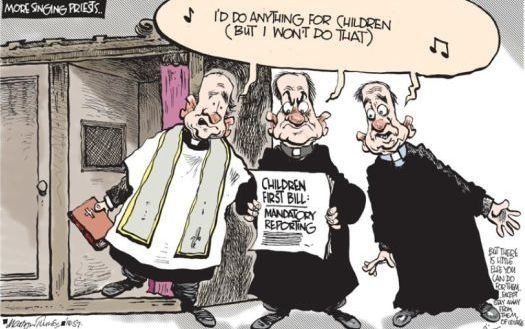

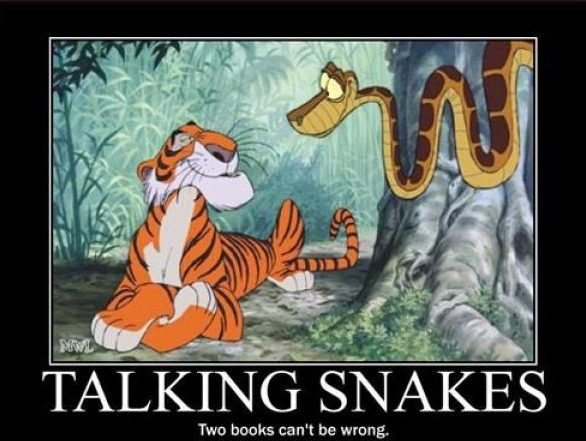

There’s this naïve notion floating around the Internet that if Evangelicals would just honestly deal with the current sex abuse scandal and make changes that protect children, all would be well within the Evangelical bubble. However, even if Evangelicals demonstrated through actions, and not words, that they really, really, really do care about sexual abuse and other sex crimes within their churches, the fact remains that their beliefs are still psychologically harmful and can, at times, lead to physical harm. Besides, I don’t think for a moment that Evangelicals will honestly and completely do something about clergy sexual misconduct. I suspect what will happen is that Evangelical pastors will put on sackcloth and ashes, wail prayers of repentance to the Ceiling God®, have staff members watch training videos and read a few books, preach a series of sermons on why preachers, deacons, Sunday school teachers, evangelists, missionaries, youth pastors, junior church teachers, and choir directors shouldn’t diddle children or fuck women who are not their wives, and then, believing they have done all they could do, go right back to their old ways. How can it be otherwise? As long as Evangelicals believe the Bible is the inspired, inerrant, infallible Word of God, they will remain joined at hip with all sorts of abhorrent anti-human, Bronze-age beliefs.

Evangelicals will still believe:

- That all of us are born broken (sinners) and in need of fixing (salvation).

- That atonement for our brokenness (sinfulness) requires blood sacrifice; particularly the blood of Jesus, the eternal son of the Protestant God.

- That God will torture non-Evangelicals for eternity in a lake of fire after death; that this torture will require God fitting unbelievers with bodies that will withstand an eternal slow-roast on God’s spit.

- That people who are non-Evangelicals solely due to who their parents are and where they were born will suffer endless torment for not believing in a Jesus they never heard of.

- That someday soon, God will pour out his wrath and judgment on unbelievers; subjecting them to all sorts of pain and suffering. This same God will slaughter everyone on earth and then renovate the earth with fire.

- That marriage is only between a man and a woman, and that the only permissible sex is within the bond of marriage, in the missionary position, and primarily for the propagation of the human race.

- That husbands are the heads of their homes, and wives are to submit their authority; that God has ordained a certain structure for the family; that women are best suited for cleaning house, cooking meals, changing diapers, and spreading their legs whenever their husbands demand it.

- That atheists, agnostics, humanists, liberals, and other non-Evangelicals are tools of Satan, used by him to deceive the masses.

- That same-sex marriage, homosexuality, premarital sex, abortion, liberal politics, socialism, and a host of other social issues/practices are abominations to God.

Shall I go on? My problems with Evangelicalism are theological, social, and political. I can’t think of one good reason to recommend anyone attend an Evangelical church. If someone must hang on to their belief in the Christian God, there are kinder, gentler expressions of faith; places that believe in science, promote intellectual inquiry, and support pro-human programs. The best advice I can give to Evangelicals is to RUN!

Note

I am aware that the aforementioned statement of Evangelical beliefs does not apply fully to all Evangelicals; that some Evangelicals differ with others in finer points of doctrine and practice. If what I wrote above doesn’t apply to you, keep on moving. There are millions of people behind you that believe all of these things to the letter.

About Bruce Gerencser

Bruce Gerencser, 61, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 40 years. He and his wife have six grown children and twelve grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist. For more information about Bruce, please read the About page.

Bruce is a local photography business owner, operating Defiance County Photo out of his home. If you live in Northwest Ohio and would like to hire Bruce, please email him.

Thank you for reading this post. Please share your thoughts in the comment section. If you are a first-time commenter, please read the commenting policy before wowing readers with your words. All first-time comments are moderated. If you would like to contact Bruce directly, please use the contact form to do so.

Donations are always appreciated. Donations on a monthly basis can be made through Patreon. One-time donations can be made through PayPal.