As a devout Evangelical Christian for almost fifty years, I never doubted or questioned the Bible. How could I? The Bible was God’s Word — inspired, inerrant, and infallible. To question the Bible was to question God himself. Certainly, I came across passages of Scripture that didn’t make sense to me or seemed to contradict other passages of Scripture, but I never doubted the teachings of the Bible. I believed God would make these verses clear to me in time, and if he didn’t, I would still trust him, believing, by faith, that all things would be made known, if not on Earth, in Heaven.

As an Evangelical-preacher-turned-atheist, I am free to read and question the Bible at will. No more faithing-it or trusting that God would make all things known to me. As a result, the Bible reads very differently for me than it did when I was a hellfire-and-brimstone, old-fashioned, sin-hating, Holy Ghost-filled Baptist preacher.

In Genesis 2, we find God giving a command to Adam and Eve:

And the Lord God took the man, and put him into the garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it. And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat: But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.

Genesis 3 adds:

And when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband with her; and he did eat. And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked;

….

And the Lord God said, Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil: and now, lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever: Therefore the Lord God sent him forth from the garden of Eden, to till the ground from whence he was taken.So he drove out the man; and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.

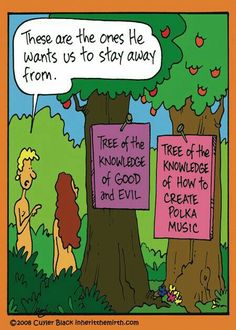

God planted a tree in the Garden of Eden whose fruit would give a person the knowledge of good and evil if he ate the proverbial apple. Strangely, Eve knew that eating the fruit would make her wise. How did she know this? There was another tree in the garden, the Tree of Life. Eating from this tree would give the eater eternal life.

God told Mr. and Mrs. Adam that the day they ate from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, they would die. This did not stop the first humans from plucking a shiny red apple from the tree. Both Adam and Eve ate the fruit. Did they immediately die? No, they lived for hundreds of years afterward. God lied to them when he said, “For in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.”

Further, who was the LORD talking to when he said, “Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil: and now, lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever.” While we cannot be certain who the LORD was speaking to, it is likely some sort of heavenly beings or gods. The LORD feared Adam and Eve would become eternal gods if they gained access to the Tree of Life, so he placed Cherubims and a flaming sword at the entrance of the Garden of Eden, forever barring humans access to the Tree of Life.

If God is sovereign and knows the end from the beginning, he knew beforehand everything Adam, Eve, and the Serpent (who is never called the Devil or Satan) would do. Why create the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil? Why tempt Adam and Eve when you knew they would fail? According to Evangelicals, everything bad, sinful, and evil flows from the moment Adam and Eve ate the apple. Wouldn’t it have been better to put the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in the equivalent of Fort Knox, safe and secure from human access? Instead, God put fresh-baked cookies on the kitchen counter, thinking they would be safe from children seeing and eating them. As any grandparent knows, cookies are kryptonite for children (and adults too). Want to keep your grandkids out of the cookies? Put them away where they can’t find them. Why didn’t God do the same for Adam and Eve and the whole human race?

These are the sorts of issues you must wrestle with if you are a Bible literalist. If, on the other hand, you think Genesis 1-3 is a fictional story, poetry, or metaphors, the aforementioned story makes perfect sense as the author attempts to explain why the world is the way it is. It is literalists who are forced to come up with all sorts of insane interpretations to justify their reading of the text.

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.