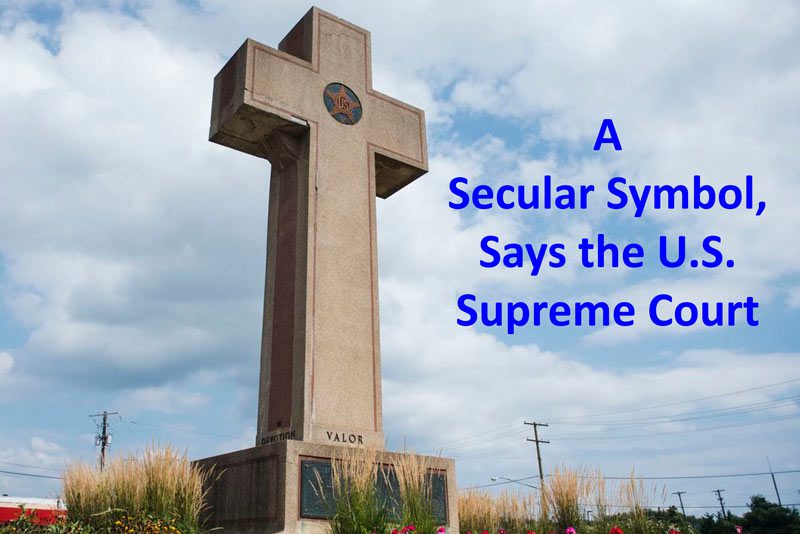

An immense Latin cross stands on a traffic island at the center of a busy three-way intersection in Bladensburg, Md. “Monumental, clear, and bold” by day, the cross looms even larger illuminated against the night-time sky. Known as the Peace Cross, the monument was erected by private citizens in 1925 to honor local soldiers who lost their lives in World War I. “The town’s most prominent symbol” was rededicated in 1985 and is now said to honor “the sacrifices made in all wars,” by “all veterans.” Both the Peace Cross and the traffic island are owned and maintained by the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, an agency of the state of Maryland.

Decades ago, this court recognized that the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution demands governmental neutrality among religious faiths, and between religion and nonreligion. Numerous times since, the court has reaffirmed the Constitution’s commitment to neutrality. Today, the court erodes that neutrality commitment, diminishing precedent designed to preserve individual liberty and civic harmony in favor of a “presumption of constitutionality for longstanding monuments, symbols and practices.”

The Latin cross is the foremost symbol of the Christian faith, embodying the “central theological claim of Christianity: that the son of God died on the cross, that he rose from the dead, and that his death and resurrection offer the possibility of eternal life.” Precisely because the cross symbolizes these sectarian beliefs, it is a common marker for the graves of Christian soldiers. For the same reason, using the cross as a war memorial does not transform it into a secular symbol, as the courts of appeals have uniformly recognized.

Some of my colleagues suggest that the court’s new presumption extends to all governmental displays and practices, regardless of their age. ‘A more contemporary state effort’ to put up a religious display is ‘likely to prove divisive in a way that a longstanding, pre-existing monument would not.’” I read the court’s opinion to mean what it says: “Retaining established, religiously expressive monuments, symbols, and practices is quite different from erecting or adopting new ones,” and, consequently, only “longstanding monuments, symbols, and practices” enjoy “a presumption of constitutionality.”

Cross not suitable for other faiths

Just as a Star of David is not suitable to honor Christians who died serving their country, so a cross is not suitable to honor those of other faiths who died defending their nation. Soldiers of all faiths “are united by their love of country, but they are not united by the cross.” By maintaining the Peace Cross on a public highway, the commission elevates Christianity over other faiths, and religion over nonreligion. Memorializing the service of American soldiers is an “admirable and unquestionably secular” objective.

But the commission does not serve that objective by displaying a symbol that bears “a starkly sectarian message.” The First Amendment commands that the government “shall make no law” either “respecting an establishment of religion” or “prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Adoption of these complementary provisions followed centuries of “turmoil, civil strife, and persecution, generated in large part by established sects determined to maintain their absolute political and religious supremacy.”

Mindful of that history, the fledgling Republic ratified the Establishment Clause, in the words of Thomas Jefferson, to “build a wall of separation between church and state.”

Government may not favor

The Establishment Clause essentially instructs: “The government may not favor one religion over another, or religion over irreligion.”

In cases challenging the government’s display of a religious symbol, the court has tested fidelity to the principle of neutrality by asking whether the display has the “effect of ‘endorsing’ religion.” The display fails this requirement if it objectively “conveys a message that religion or a particular religious belief is favored or preferred.” To make that determination, a court must consider “the pertinent facts and circumstances surrounding the symbol and its placement.”

As I see it, when a cross is displayed on public property, the government may be presumed to endorse its religious content. The venue is surely associated with the state; the symbol and its meaning are just as surely associated exclusively with Christianity.

To non-Christians, nearly 30 percent of the population of the United States, the state’s choice to display the cross on public buildings or spaces conveys a message of exclusion: It tells them they “are outsiders, not full members of the political community.”

“For nearly two millennia,” the Latin cross has been the “defining symbol” of Christianity, evoking the foundational claims of that faith. Christianity teaches that Jesus Christ was “a divine Savior” who “illuminated a path toward salvation and redemption.” Central to the religion are the beliefs that “the son of God,” Jesus Christ, “died on the cross,” that “he rose from the dead,” and that “his death and resurrection offer the possibility of eternal life.” “From its earliest times,” Christianity was known as “religio crucis — the religion of the cross.”

Christians wear crosses, not as an ecumenical symbol, but to proclaim their adherence to Christianity. An exclusively Christian symbol, the Latin cross is not emblematic of any other faith.

The principal symbol of Christianity around the world should not loom over public thoroughfares, suggesting official recognition of that religion’s paramountcy.

The commission’s “attempts to secularize what is unquestionably a sacred symbol defy credibility and disserve people of faith.” The asserted commemorative meaning of the cross rests on — and is inseparable from — its Christian meaning: “the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and the redeeming benefits of his passion and death,” specifically, “the salvation of man.” Because of its sacred meaning, the Latin cross has been used to mark Christian deaths since at least the fourth century. The cross on a grave “says that a Christian is buried here,” and “commemorates that person’s death by evoking a conception of salvation and eternal life reserved for Christians.”

As a commemorative symbol, the Latin cross simply “makes no sense apart from the crucifixion, the resurrection, and Christianity’s promise of eternal life.” The cross affirms that, thanks to the soldier’s embrace of Christianity, he will be rewarded with eternal life. “To say that the cross honors the Christian war dead does not identify a secular meaning of the cross; it merely identifies a common application of the religious meaning.” Scarcely “a universal symbol of sacrifice,” the cross is “the symbol of one particular sacrifice.”

Every court of appeals to confront the question has held that “making a . . . Latin cross a war memorial does not make the cross secular,” it “makes the war memorial sectarian.” The Peace Cross is no exception. That was evident from the start. At the dedication ceremony, the keynote speaker analogized the sacrifice of the honored soldiers to that of Jesus Christ, calling the Peace Cross “symbolic of Calvary,” where Jesus was crucified. Local reporters variously described the monument as “a mammoth cross, a likeness of the Cross of Calvary, as described in the bible,” “a monster Calvary cross,” and “a huge sacrifice cross.”

The character of the monument has not changed with the passage of time.

Not a universal symbol

Reiterating its argument that the Latin cross is a “universal symbol” of World War I sacrifice, the commission states that “40 World War I monuments . . . built in the United States . . . bear the shape of a cross.” This figure includes memorials that merely “incorporate” a cross. Moreover, the 40 monuments compose only 4 percent of the “948 outdoor sculptures commemorating the First World War.” The court lists just seven freestanding cross memorials, less than 1 percent of the total number of monuments to World War I in the United States. Cross memorials, in short, are outliers. The overwhelming majority of World War I memorials contain no Latin cross. In fact, the “most popular and enduring memorial of the post-World War I decade” was “the mass-produced Spirit of the American Doughboy statue.” That statue, depicting a U.S. infantryman, “met with widespread approval throughout American communities.”

The Peace Cross, as plaintiffs’ expert historian observed, was an “aberration . . . even in the era in which it was built and dedicated.” Like cities and towns across the country, the United States military comprehended the importance of “paying equal respect to all members of the Armed Forces who perished in the service of our country,” and therefore avoided incorporating the Latin cross into memorials. The construction of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is illustrative. When a proposal to place a cross on the Tomb was advanced, the Jewish Welfare Board objected; no cross appears on the Tomb. In sum, “there is simply ‘no evidence . . . that the cross has been widely embraced by’ — or even applied to — ‘non-Christians as a secular symbol of death’ or of sacrifice in military service” in World War I or otherwise.

The Establishment Clause, which preserves the integrity of both church and state, guarantees that “however . . . individuals worship, they will count as full and equal American citizens.”

“If the aim of the Establishment Clause is genuinely to uncouple government from church,” the clause does “not permit . . . a display of the character” of Bladensburg’s Peace Cross.

— This is an edited and condensed version of the dissent, written by Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in the Bladensburg cross case