For those of us who came of age in Evangelical churches in the late 1960s and 1970s, we remember countless sermons about the rapture, the second coming of Jesus, and the Great Tribulation. The classic Evangelical horror flick, A Thief in the Night, was released in 1972. Wikipedia explains the plot of A Thief in the Night this way:

A young woman named Patty Myer awakens one morning to a radio broadcast announcing the disappearance of millions around the world showing that the rapture has occurred. She finds that her family has disappeared and that she has been left behind. The United Nations sets up an emergency government system called the United Nations Imperium of Total Emergency (UNITE) and declare that those who do not receive The Mark of the Beast identifying them with UNITE will be arrested.

Several flashbacks occur to times in Patty’s life before the rapture has happened. The flashbacks also show her two friends and their different approaches to Christianity, one who considers Jesus Christ her Only Lord and Only Savior and the other, Diane, who does not take it seriously. Patty considers herself a Christian because she occasionally reads her Bible and goes to church regularly, where the pastor is really an unbeliever. She refuses to believe the warnings of her friends and family that she will go through The Great Tribulation if she does not accept Jesus Christ as her Only Lord and Only Savior. One morning, she awakens to find that her family and millions of others have suddenly disappeared.

Patty seems a strange breed of person who both refuses to trust Jesus Christ as her Only Lord and Only Savior and also refuses to take The Mark. Patty desperately tries to avoid the law and The Mark but is captured by UNITE. Patty escapes but, after a chase, is cornered by UNITE on a bridge and falls from the bridge to her death.

Patty then awakens, and the entire film’s plot is revealed to have been a dream. She is tremendously relieved; however, her relief is short-lived when the radio announces that millions of people have in fact disappeared. Horrified, Patty frantically searches for her family only to find them missing too. Traumatized and distraught, Patty realizes that The Rapture has indeed occurred, and she has been left behind. In the ensuing plot the questions are whether or not she will be caught, as she was in her dream, and whether or not she will choose to take The Mark to escape execution.

A Thief in the Night profoundly affected scores of Evangelical Christians. Here was a movie showing in graphic detail what would happen when Jesus comes to earth and raptures away Christians. This movie and Estus Pirkle’s 1974 horror flick, The Burning Hell, unsettled me emotionally and spiritually. Was I ready for the rapture? What if I wasn’t saved? These issues and others certainly played a part in my conversion at Trinity Baptist Church in Findlay, Ohio in the fall of 1972. (Please see The Sounds of Fundamentalism: A Thief in the Night by Russell S. Doughten and The Sounds of Fundamentalism: The Burning Hell by Estus Pirkle and Ron Ormond.)

The 1970s featured prophecy-themed sermons from the books of Revelation and Daniel. In 1976, the Walking Bible, Evangelist Jack Van Impe came to Findlay to hold a city-wide crusade. Van Impe’s sermons were filled with warnings about the imminent return of Jesus and the Great Tribulation. I attended a Bob Harrington crusade (please see Evangelist Bob Harrington: It’s Fun Being Saved) that featured several sermons about the soon return of Jesus. The widely-read Sword of the Lord ran regular articles and sermons about the pretribulational rapture of the church and the horrors of the soon-coming Tribulation.

Much of the evangelistic frenzy in the 1970s was driven by the belief that Jesus was preparing to come back soon — maybe today! Independent Fundamentalist Baptist (IFB) churches, in particular, grew quickly, so much so that many of the largest churches in the United States were IFB congregations.

Of course, Jesus did not return in the 1970s. The 1980s saw Hal Lindsay’s book, The Late, Great Planet Earth, first published in 1970, which renewed Evangelical fervor with its prediction that the rapture would take place 40 years after the 1948 establishment of Israel as a nation. Lindsay’s book, The 1980s: Countdown to Armageddon, continued to stoke the fires of Evangelical zeal. (By 1990, The Late, Great Planet Earth had sold 28 million copies.) In 1988, Edgar Whisenant released a publication titled 88 Reasons Why the Rapture Will be in 1988. (88 Reasons sold 4.5 million copies, and 300,000 free copies were mailed to pastors.) Whisenant predicted the rapture would occur between September 11 and 13, 1988. Jesus, of course, was a no-show in 1988 and has yet to make an appearance to this day.

By the time the 1990s arrived, rapture mania had pretty much died out. Oh, Evangelical pastors and evangelists still preached eschatologically themed sermons, but the fervor that drove churches previously was gone. While preachers still preach about the imminent return of Jesus, such sermons no longer motivate congregants to busily win souls before Jesus comes again and it is too late.

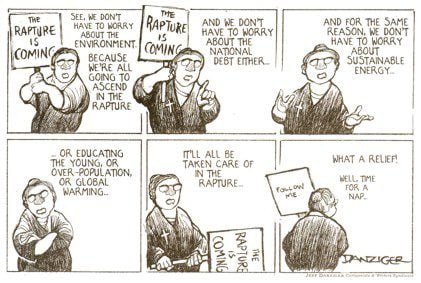

Officially, most Evangelicals believe in the pretribulational rapture of the church. However, if you let their works testify to what they really believe, it is evident that Evangelicals no longer believe that Gabriel is fixing to blow his trumpet and Jesus is returning in the clouds to catch away his chosen ones. TV preachers such as con artist Jim Bakker continue to preach up the could-be-tomorrow rapture, but tomorrow never comes and their bank accounts continue to grow.

Evangelicals have traded a soon-coming Lord for megachurches, fancy AV systems, praise bands, relational preaching and, most importantly, political power. Evangelicals seem far more concerned with expanding their kingdoms on Earth than they are with evangelizing the lost and building the Kingdom of Heaven. I don’t know of one Evangelical preacher, church leader, or congregant, for that matter, who lives as if Jesus could split the eastern sky today. I told Polly that Evangelicals sure do talk and sing a lot about Heaven, but none of them seem to be in much hurry to get there. The vast majority of Evangelicals not only are indifferent about their own souls, but they also couldn’t care less about the souls of their unsaved, heathen neighbors. Evangelicalism has become that which it stood against decades ago — institutionalized. It has become little more than a cultural religion. The only reason any of us should give a thought about Evangelicalism is that it continues to have a dangerous anti-human hold on the Republican Party. Unbelievers now outnumber Evangelicals in the United States, but we have nowhere near the political and cultural power Evangelicals have.

Evangelicals can continue to preach up the soon return of Jesus, but it’s evident to anyone who is paying attention that they no longer believe what they are preaching. In fact, I suspect many Evangelicals hope Jesus isn’t in any hurry to destroy the world with fire. Deep down, most Evangelicals wonder if they really want to trade the good life of the here and now for an eternity of prostrating themselves before a narcissistic God.

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.