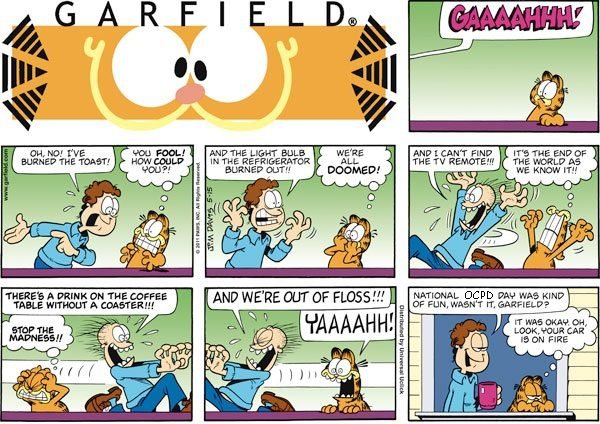

I have battled Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD) for most of my adult life. While OCPD and OCD have some similarities, there are differences, namely:

- People with OCD have insight, meaning they are aware that their unwanted thoughts are unreasonable. People with OCPD think their way is the “right and best way” and usually feel comfortable with such self-imposed systems of rules.

- The thoughts, behaviors and feared consequences common to OCD are typically not relevant to real-life concerns; people with OCPD are fixated with following procedures to manage daily tasks.

- Often OCD interferes in several areas in the person’s life including work, social and/or family life. OCPD usually interferes with interpersonal relationships, but makes work functioning more efficient. It is not the job itself that is hurt by OCPD traits, but the relationships with co-workers, or even employers can be strained.

- Typically, people with OCPD don’t believe they require treatment. They believe that if everyone else conformed to their strict rules, things would be fine! The threat of losing a job or a relationship due to interpersonal conflict may be the motivator for therapy. This is in contrast to people with OCD who feel tortured by their unwanted thoughts and rituals, and are more aware of the unreasonable demands that the symptoms place on others, often feeling guilty because of this.

- Family members of people with OCPD often feel extremely criticized and controlled by people with OCPD. Similar to living with someone with OCD, being ruled under OCPD demands can be very frustrating and upsetting, often leading to conflict. (OCPD Fact Sheet)

I have been considered a perfectionist most of my life, a badge I wore with honor for many years, and one I still wear on occasion. As we age — I am now sixty-five — we tend to reflect on our lives and how we got where we are today. Self-reflection and assessment are good, allowing us the opportunity to be honest about the path we have taken and choices we have made in life.

When I first realized twenty or so years ago that I had a problem — a BIG problem that was harming my wife and children — the first thing I did was try to figure out how I ended up with OCPD. While my mother had perfectionist tendencies, she was quite comfortable living in the midst of clutter and disarray (but not uncleanliness). I concluded that it was my Fundamentalist Christian upbringing with its literalistic interpretations of the Bible that planted in me the seeds of what would one day become OCPD. I spent most of my adult life diligently and relentlessly striving to follow after Jesus and to keep his commandments. But try as I might, I still continued to come up short. This, of course, only made me pray more, study more, give more, driving me to allot more and more of my time to God/church/ministry. In doing so, the things that should have mattered the most to me — Polly, our children, my health, and enjoying life — received little attention. Polly was taught at Midwestern Baptist College — the IFB institution both of us attended in the 1970s — that she would have to sacrifice her relationship with me for the sake of the ministry. I was, after all, a divinely called man of God. Needless to say, for way too many years, our lives were consumed by Christianity and the work of the ministry, so much so that we lost all sense of who we really were.

Perhaps someday several of my children will write about growing up in a home with a father who had OCPD. The stories are humorous now, but not so much when they were lived out in real-time. My children are well versed in Dad’s rules of conduct. Granted, some of these rules such as “do it right the first time” have served them well in their chosen fields of employment, but their teacher was quite the taskmaster, and I am certain there were better ways for them to learn these rules.

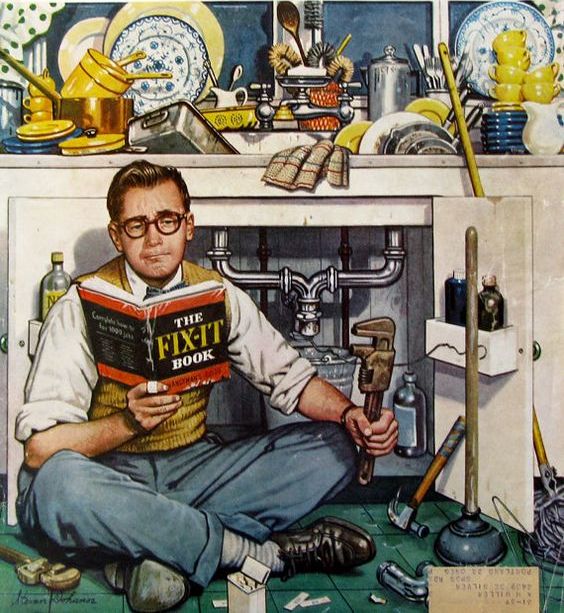

My oldest sons “fondly” remember helping me center the church pulpit, right down to one-sixteenth of an inch. Did it matter if the pulpit was slightly off-center? For most people — of course not; but, for me it did. I felt the same way about how I prepared my sermons, folded the bulletins, cleaned the church, and didcountless other day-to-day responsibilities. When I took on secular jobs, employers loved me because I was a no-nonsense, time-to-lean, time-to-clean manager. (Is it any surprise that most of my adult jobs were either pastoring churches or management jobs?)

People walking into my study were greeted by a perfectly cleaned and ordered office. The desktop was neat, and the drawers were organized, with everything having a place. My bookshelves were perfectly ordered from tallest to smallest book and then by subject. Dress-wise, I wore white one-hundred-percent pinpoint cotton shirts and black wingtip shoes. My suits were well-kept and matched whatever tie I was wearing. My appearance mattered to me. Congregants knew they would never find me shopping at the local Walmart wearing a tee-shirt and sweatpants.

What I have mentioned above sounds fine, right? Surely, I should have a right to order my life any way I want to. And that would be true, except for the fact that I live in a world populated by other people; people who are not like me; people who are happy with clutter, disarray, and OMG even dirt! It is in their personal relationships that people with OCPD have problems, and, in some instances, they can drive away the very people who love them.

For the first twenty-five years of marriage, my relationship with Polly was defined by Fundamentalist/patriarchal thinking. It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that such beliefs play well in the minds of people with OCPD. I had high expectations not only for myself, but for my wife and children too. We all, of course, miserably failed, but all that did was increase the pressures to conform to silly (and at times harmful) behavioral expectations. It didn’t help matters that I was an outgoing decision-maker married to a passive, always-conform-to-the-wishes-of-others, woman. While we put on quite a dog and pony show for most of our time in the ministry, behind the scenes things were not as they outwardly appeared to be.

Towards the end of my time in the ministry — the early 2000s — I began to see how harmful my behavior was when it came to my familial relationships (and to a lesser degree my relationship with congregants). While it would be another decade before I would finally seek out professional secular counseling, I did begin to make changes in my life. These changes caused a new set of conflicts due to the fact that everyone was used to me being the boss, with everything being according to MY plan. While Polly and the kids loved their new-found freedom, there were times where they were quite content to let me be the stern patriarch. As with all lasting change, it takes time to undo deeply-seated behaviors.

I am not so naive as to believe that I am “cured” of OCPD. I am not. My counselor is adept at pointing out to me when certain behaviors of mine move toward what she calls my OCD tendencies. I have had to be repeatedly schooled in the difference between good/bad and different. For example, young people today generally discipline their children differently from their baby-boomer parents. Read enough memes on Facebook and you will conclude that young parents have lost their minds when it comes to raising their children. What that brat needs is an ass-whipping, boomer grandparents say. What I continue to learn is that people who act differently from me, look different from me, or have beliefs different from mine are not necessarily wrong/bad. Most often, what they really are is “different.” Learning to be at peace with differences has gone a long way in muting my OCPD thinking.

Both Polly and I agree that the last fifteen or so years of married life have been great. One of the reasons for this has been my willingness to realize where my OCPD is causing harm and making the necessary changes to end the harm. The first thing I learned is that everyone is entitled to his or her own space. I have every right to order my office, drawers, and space as I want them to be. I no longer apologize for having OCPD. All that I ask of others is that when they invade my space, they respect my wishes. And that works for others too. I have to respect the personal boundaries of Polly and our children. This is why I do not meddle in the lives of my children. I give advice when asked, but outside of that, they are free to live as they please. Do my children make decisions I disagree with, decisions that leave me mumbling and cussing? Yep, but it’s their lives, not mine, and I love them regardless of the choices they make.

The second thing I learned is that it is important for Polly and me to have times of distance from each other. It is okay for each of us to do things without the other. We don’t have to like all the same things. Understanding this has allowed Polly’s life to blossom in ways I could never have imagined. If you had known Polly in 1999 and then met the 2022 version, why you would wonder if she is possessed. From going back to college and graduating, to becoming an outspoken manager at work, Polly is an awesome example of what someone can become once the chains of Fundamentalism and patriarchal thinking have been broken.

The third thing I learned is that my OCPD can be productively channeled, with my personal relationships surviving afterward. Polly loves it when she comes home and finds that I have emptied the cupboards, cleaned them, and replaced everything neatly and in order. The joke in the family is that people want me to come clean their house for them, but they can’t stand being around me when I do. In the public spaces where our lives collide, Polly and I have had to learn to give and take. I have learned that it is okay to leave the newspaper on the floor until tomorrow, and Polly has learned, come holidays, that I am going to clean every inch of the house, including under the refrigerator — with her help of course. She will never understand why my underwear drawer needs to be straightened up for company, and she will likely never understand the need to clean under the stove/refrigerator four times a year. But, because she loves me, she smiles and says, what do you need me to do next?

My chronic health problems and unrelenting pain have forced me to let go of some of my obsessions. I can’t, so I don’t. I don’t find this giving in/giving up easy to deal with, but I have come to see that life is too short for me to not enjoy the moment even if everything is not in perfect order. That said, I still have OCPD moments, and I suspect I always will. Several years ago, I had a dentist appointment. The dental assistant had me take a seat in the exam room. When she returned, she found me tapping the valance on the blind with my cane. I told her, I have been sitting here for years with that crooked valance driving me crazy. There, it’s fixed! She laughed. Later, she returned and told me that all the valances in the other rooms were off-center too. She said, I never noticed that until you pointed it out to me. I likely will always have an eye for when something is crooked, especially wall hangings and sign lettering. Why can’t the doctor’s office get notices straight when they tape them on the wall, right? Dammit, how hard is it to do the job right the first time! Sigh. You see, OCPD never completely goes away, but it can be managed and controlled, allowing me, for the most part, to have satisfying and happy relationships with the people I love.

Do you have OCPD or OCD tendencies? Please share your experiences in the comment section. I am especially interested in hearing about how Fundamentalism affected your behavior.

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.