I just now – fifteen minutes ago – came to realize with the most crystal clarity I have ever had why I cannot call myself a Christian. Of course, as most of you know, I have not called myself a Christian publicly for a very long time, twenty years or so I suppose. But a number of people tell me that they think at heart I’m a Christian, and I sometimes think of myself as a Christian agnostic/atheist. Their thinking, and mine, has been that if I do my best to follow the teachings of Jesus, in some respect I’m a Christian, even if I don’t believe that Jesus was the son of God, or that he was raised from the dead, or that… or even that God exists. In fact I don’t believe all these things. But can’t I be a Christian in a different sense, one who follows Jesus’ teachings?

Fifteen minutes ago I realized with startling clarity why I don’t think so.

This afternoon in my undergraduate course on the New Testament I was lecturing on the mission and message of Jesus.

….

In today’s lecture I wanted to introduce, explain, and argue for the view that has been dominant among critical scholars studying Jesus for the past century, that Jesus is best understood as a Jewish apocalypticist. I warned the students that this is not a view they will have encountered in church or in Sunday school. But there are solid reasons for thinking it is right. I tried to explain at some length what those reasons were.

But first I gave an extended account of what Jewish apocalypticists believed. The entire cosmos was divided into forces of good and evil, and everything and everyone sided with one or the other. This cosmic dualism worked itself out in a historical dualism, between the current age of this world, controlled by forces of evil, and the coming age, controlled by the forces of good. This age would not advance to be a better world, on the contrary, apocalypticists thought this world was going to get worse and worse, until literally, at the end, all hell breaks out.

But then God would intervene in an act of cosmic judgment in which he destroyed the forces of evil and set up a good kingdom here on earth, an actual physical kingdom ruled by his representative. This cataclysmic judgment would affect all people. Those who had sided with evil (and prospered as a result) would be destroyed, and those who had sided with God (and been persecuted and harmed as a result) would be rewarded.

Moreover, this future judgment applied not only to the living but also to the dead. At the end of this age God would raise everyone from the dead to face either eternal reward or eternal punishment. And so, no one should think they could side with the forces of evil, prosper as a result, become rich, powerful, and influential, and then die and get away with it. No one could get away with it. God would raise everyone from the dead for judgment, and there was not a sweet thing anyone could do to stop him.

And when would this happen? When would the judgment come? When would this new rule, the Kingdom of God, begin? “Truly I tell you, some of you standing here will not taste before you see the kingdom of God come in power.” The words of Jesus (Mark 9:1). Jesus was not talking about a kingdom you would enter when you died and went to heaven: he was referring to a kingdom here on earth, to be ruled by God . Or as he says later, when asked when the end of the age would come, “Truly I tell you, This generation will not pass away before all these things take place.”

….

When I finished laying it all out in my lecture, stressing that Jesus thought this all was going to happen within his own generation, I had about two minutes left, and I had a final point to make (on my PowerPoint outline): “Jesus Now and Then.” Today the idea that Jesus expected the imminent end of the age to be brought in a cataclysmic act of judgment leading to a world of peace and universal happiness is no longer preached or taught in churches (well, the vast majority of churches). But it does appear to be who Jesus really was.

I told my students they had to decide for themselves if they agreed with this scholarly view or not, after looking at all the evidence. But I stressed that they should not reject the view (historically) simply because they thought it was wrong religiously (since Jesus then would have been wrong about when the end would come). I then explained why, and it was when I gave this explanation – impromptu, off the top of my head – that I realized why it was that I was not and could not be a follower of Jesus’ teachings.

I told my students that the apocalyptic Jesus realized that ultimate reality and true meaning do not reside in this world. Following Jesus means to realize that ultimate reality resides outside this world, in a higher world, above this mundane existence that we live in the here and now. I stated this as emphatically as I could. Students surely thought I was preaching, that I was affirming this message. I made the statement as rhetorically effective as I could.

And I’m not sure I’ve ever said it this way before in my 32 years of teaching. When I said it I had two immediate mental reactions to what I had just said: (a) I realized that I really do think this is Jesus’ ultimate (apocalyptic point) and, even more graphically, (b) I don’t agree with that view at all.

My personal view is just the opposite. My view is that there is no realm above or outside of this one that provides meaning to life in our world. In my view this world is all there is. Yes, I know there are aspects of physical reality that are extremely odd and completely inaccessible to me. But I don’t think there is anything outside our material existence. Meaning comes from what we can value, cherish, prize, aspire to, hopeful, achieve, attain, and … love in this world. There is no transcendent truth that can make sense of our reality. Our reality is the only reality. It can either be (very) good for us or (very) bad for us. But however we experience it, it’s all there is.

That’s what I really think. I never push this view on anyone else. It’s simply my view. And I think it is diametrically (not just tangentially) different from the view of Jesus. It is completely at odds with his view. That’s why I don’t think I do subscribe to his teachings, his views, or his message (in some metaphorical way).

For lots of personal reasons I do find that sad, but I’m afraid it appears to be the case.

— Bart Ehrman, The Bart Ehrman Blog, Why I am Not a Christian, March 6, 2017

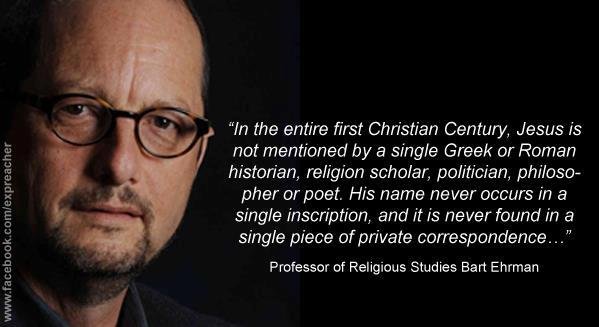

I know that Ehrman is not a mythicist, and indeed has a rancourous relationship with Richard Carrier on the subject, yet the quote that accompanies the picture implies that he could well be one. Some day I must get round to reading Ehrman on the subject but, in the meantime, it’s great that after all these years he still has insights that he hasn’t previously had. It’s a pity that the religious never seem to experience this.

Not the best reference source as Ehrman has been found to be wrong on a number of his claims about Christianity, the church and Christ himself.

Sure he has, yet he is still a distinguished scholar at the University of North Carolina. It is Evangelicals who primarily object to Ehrman’s conclusions. Of course, these “scholars” object to anything that challenges Evangelical dogma.

In the main, Ehrman advances positions held by most scholars not associated with Evangelical institutions. Disagreement comes not from the evidence (facts) but the conclusions Ehrman draws from the historical, theological, and textual evidence.

The difference, I suspect, is that Ehrman will answer to being called wrong and respond. The Church does not reason. It simply says, The Bible says! It does not need proofs, only magical faith. IT CHANGED ME FROM A SUICIDAL, HOMICIDAL MANIAC, THEREFORE!

How can he be “found to be wrong”? He can be disagreed with, but matters of faith can’t be proved or disproved. That’s the nature of faith: you believe without proof.

I think you miss the point in that faith is required when the evidence suggests otherwise. The word ‘proof’ is inappropriate in the manner you suggest, as nothing is provable outside of pure mathematics. In the real world we limit ourselves to the preponderance of evidence and the preponderance of the evidence is that the bible is of human origin, that Jesus of the bible did not exist, and that there is no afterlife. Ehrman discusses and reviews issues that surround the evidence, and in that sense he can absolutely be right or wrong though, unusually, his biggest critic (in the sense of most reasoned) is himself.

This quote is misquoted. Read the book of Ehrman that it’s in.

This post is excerpted from Ehrman’s blog, of which I am a member. Or are you referencing the graphic?