After my freshman year of classes at Midwestern Baptist College in Pontiac, Michigan, I returned home to my mother’s palatial palace — also known as a trailer — on U.S. Hwy. 6, five miles southwest of Bryan, Ohio. I had come home to work, hoping to earn enough money to pay for my next year of college. I accepted a first-shift machine operator position at Holabird Manufacturing, a manufacturer of cheap trailer furniture. Holabird would later close its doors and file for bankruptcy in 1983. I also worked a second shift job at Bard Manufacturing, a maker of HVAC units. I was attending First Baptist Church in Bryan at the time. One of the church’s deacons was a manager for Bard. He graciously arranged for Bard to hire me for the summer.

I was twenty years old in the summer of 1977; strong, fit, and full of energy. Had I not been, I would never have been able to work eighty hours a week: 7:00 AM to 3:00 PM at Holabird and 4:00 PM to midnight at Bard. I didn’t catch up on sleep on the weekends either. Oh no, weekends were for running around with friends, going to one of the local lakes, or trekking to Newark to visit Polly for the day. That’s right, for the day. Polly’s mom didn’t like me and treated me like a rash she hoped would go away. I would get up early on Saturday, drive three hours southeast to Newark, spend as much time as I could with Polly, and turn around and drive back to Bryan. (Under no circumstances would Polly’s mom let me spend the night.) On more than one occasion, I was so exhausted that I pulled off along the road and slept for several hours. The things we’ll do for love, right?

I followed the aforementioned schedule for twelve weeks. Come late August, it was time for me to return to Midwestern to begin my sophomore year. I packed my belongings into my car and headed in the general direction of Pontiac, Michigan. As I neared Toledo, I decided to take U.S. Route 23 to Pontiac. Ninety minutes into my drive, I exited the highway into a rest stop. I needed to stretch my legs and use the restroom. As I walked towards the restroom, a 30-ish large-breasted black woman wearing revealing clothing came up to me and said, Do you want a date, Hon? Confused, I replied, excuse me? The woman repeated, Do you want a date? I smiled and said to her, no thanks, I already have a girlfriend. And with that, I continued walking to the restroom. As I walked back to my car, I saw the woman walking with a man towards a parked delivery van.

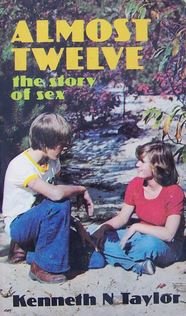

I was quite naïve when it came to matters of sex. My sex education consisted of reading an Evangelical book titled Almost Twelve and six years of locker room sex ed. I knew the fundamentals, but as far as a broader understanding of human sexuality and its darker, seamier side, I knew nothing. And as ignorant as I was, my fiancée was even worse. One warm day in the spring of 1977, Polly was in the college parking lot, sitting in her car — a 1972 AMC Hornet. Purchased new in 1972 by Polly’s father after the family car broke down during a vacation in California, by 1977 the car was already worn out, a piece of junk. This car is a story unto itself, one that I will tell another day. For now, picture sweet, naïve Polly sitting in her car, AM radio blaring, singing along with Starland Vocal Band’s hit Afternoon Delight. I came up to the car window and asked what she was listening to. She replied, Afternoon Delight. I said, you know that song is about having sex! Polly replied, IT IS NOT! The song is about having fun in the afternoon. Slightly less naïve Bruce took the time to educate sheltered Polly about exactly what it was they were having fun doing in the afternoon. This lesson would pay dividends after we married and we experienced a bit of afternoon delight ourselves.

After I returned to college, I told my roommate about what the woman had asked me at the rest stop. She asked me if I wanted to have a date! Why I didn’t even know her. Why would she want me to go on a date? I already have a girlfriend. My roommate laughed and said, she was a prostitute and was asking you if you wanted to have sex with her. Really? I replied. Yes, really. I would receive many more such lessons over the next year.

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.