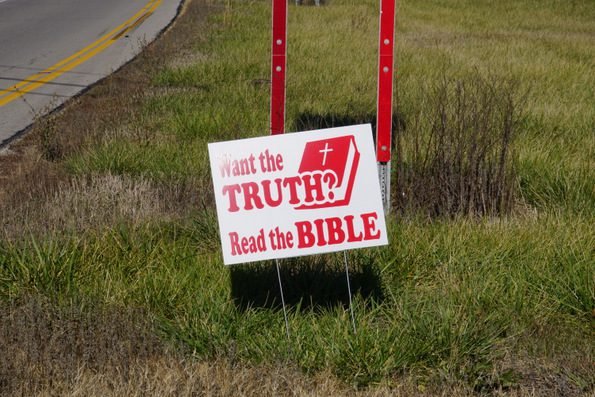

According to most Evangelicals, the Bible is not only inspired (breathed out) by God, it is also infallible and inerrant. (Please see Are Evangelicals Fundamentalists?) Since the Bible was written by men moved by the Holy Spirit or dictated by God, it stands to reason — God being perfect in all His ways — that the Bible is perfect, without error. Some Evangelicals take the notion of inerrancy even further by saying that the King James Version of the Bible is without error. And some Evangelicals — the followers of Peter Ruckman — take it further yet by saying that even the italicized words inserted by the translators of the King James Bible are divinely inspired. Other Evangelicals, thinking of themselves as more educated than other Christians, say that the “original” manuscripts from which English translations come are what are inerrant. Translations, then, are reliable, but not inerrant (even though pastors who believe this often lead churches that are filled with people who believe their leather-bound Bibles are without error). The problem with this belief is that the “originals” don’t exist. Over the years, I ran into countless Christians who believed that these so-called “originals” existed “somewhere” and that they are safely stored “somewhere.” Recently, one such ignorant Evangelical told me that I should read the Dead Sea Scrolls. In doing so, I would see that Christianity is true. Evidently, he didn’t know that the Dead Sea Scrolls don’t mention Jesus, and those who “see” Jesus in the Scrolls are either smoking too much marijuana or are importing their biased theology into the texts. Such is the level of ignorance found not only in pulpits, but in church pews.

Is the Bible in any shape or form inerrant? Of course not. Such a belief cannot rationally or intellectually be sustained. It is nothing more than wishful thinking to believe that the Bible is inerrant — straight from the mouth of God to the ears of Christians.

Dr. Bart Ehrman, a New Testament scholar and professor at the University of North Carolina, answered a question on his blog about whether believing the Bible has errors leads to agnosticism/atheism. Here is part of what Ehrman had to say:

I have never thought that recognizing the historical and literary problems of the Bible would or should lead someone to believe there is no God. The only people who could think such a thing are either Christian fundamentalists or people who have been convinced by fundamentalists (without knowing it, in many instances) that fundamentalist Christianity is the only kind of religion that is valid, and that if the assumptions of fundamentalism is flawed, then there could be no God. What is the logic of that? So far as I can see, there is no logic at all.

Christian fundamentalism insists that every word in the Bible has been given directly by God, and that only these words can be trusted as authorities for the existence of God, for the saving doctrines of Christianity, for guidance about what to believe and how to live, and for, in short, everything having to do with religious truth and practice. For fundamentalists, in theory, if one could prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that any word in the original manuscripts of the Bible was an error, than [sic] the entire edifice of their religious system collapses, and there is nothing left between that and raw atheism.

Virtually everyone who is trained in the critical study of the Bible or in serious theology thinks this is utter nonsense. And why is it that people at large – not just fundamentalists but even people who are not themselves believers – don’t realize it’s nonsense, that it literally is “non-sense”? Because fundamentalists have convinced so much of the world that their view is the only right view. It’s an amazing cultural reality. But it still makes no sense.

Look at it this way. Suppose you could show beyond any doubt that the story of Jesus walking on the water was a later legend. It didn’t really happen. Either the disciples thought they saw something that really occur [sic], or later story tellers came up with the idea themselves as they were trying to show just how amazing Jesus was, or … or that there is some other explanation? What relevance would that have to the question of whether there was a divine power who created the universe? There is *no* necessary relevance. No necessary connection whatsoever. Who says that God could not have created the universe unless Jesus walked on water? It’s a complete non sequitur.

The vast majority of Christians throughout history – the massively vast majority of Christians – have not been fundamentalists. Most Christians in the world today are not fundamentalists. So why do we allow fundamentalists to determine what “real” Christianity is? Or what “true” Christianity is? Why do we say that if you are not a fundamentalist who maintains that every word in the Bible is literally true and historically accurate that you cannot really be a Christian?

While I question how someone can be a Christian and not believe all that the Bible says is true (perhaps this is the result of a Fundamentalist hangover), I know, as Dr. Ehrman says, that hundreds of millions of people believe in the Christian God, perfect Bible or not. I am not, contrary to what my critics suggest, anti-Christian. I am, however, most certainly anti-Fundamentalist. I am indifferent towards the religious beliefs of billions of people as long as those beliefs don’t harm others. Unfortunately, many Evangelical beliefs and practices ARE harmful, and it is for this reason that I continue to write about Evangelicalism.

Inerrancy is one such harmful belief. Believing that every word of the Bible is inerrant, infallible, and true leads people to false, and at times dangerous, conclusions. Take young earth creationism — the belief that the universe was created in six literal twenty-four days, 6,024 years ago. Men such as Ken Ham continue to infect young minds with creationist beliefs which, thanks to science, we know are not true. The reason the Ken Hams of the world cannot accept what science says about the universe is because they believe the text of the Bible is inerrant. According to inerrantists, the Bible, in most instances, should be read literally. Thus, Genesis 1-3 “clearly” teaches that God created the universe exactly as young earth creationists say He did. This kind of thinking intellectually harms impressionable minds. While little can be done to keep churches, Christian schools, and home schooling parents from teaching children such absurdities, we can and must make sure Evangelical zealots are barred from bringing their nonsense into public school classrooms.

Peel back the issues that drive the culture war and what you will find is the notion that God has infallibly spoken on this or that social issue. Think about it for a moment: name one social hot button issue that doesn’t have Bible proof texts attached to it. Homosexuality? Same-sex marriage? Abortion? Premarital sex? Birth control? Marriage and divorce? Prayer and Bible reading in public schools? Every one of these issues is driven by the belief that the Bible is inerrant and that Christians must dutifully obey every word (though no Evangelicals that I know of believe, obey, and practice every law, command, precept, and teaching of the Bible). Removing the Good Book from the equation forces Evangelicals to contemplate these issues without appeals to Biblical authority and theology. As a secularist, I am more than ready and willing to have discussions with Christians about the important social issues of the day. All that I ask is that they leave their Bibles at home or stuffed under the front seats of their cars. In a secular state, religious texts of any kind carry no weight. What “God” says plays no part in deciding what our laws are. Evangelicals have a hard time understanding this, believing that their flavor of Christianity is the one true faith; believing that their infallible interpretation of a religious text written by their God is absolute truth. It is impossible to reach people who think like this.

While I at one time believed the Bible was the inspired, inerrant, infallible Word of God, it was not until I considered the possibility that the Bible might not be what I claimed it is, that I could then consider alternative ways of looking at the world. This is why I don’t argue about science with Evangelicals. I attack their foundational beliefs — that the Bible is not inerrant; that the Bible is not what they claim it is. Once the foundation is destroyed, it becomes much easier to engage Evangelicals on the issues they think are important. Given enough time, a patient agnostic/atheist/rationalist/skeptic can drive a stake into the heart of their Fundamentalist beliefs. As long as Evangelicals hang on to their “inerrant” Bibles, it is impossible to have meaningful, productive discussions with them. All anyone can do for them is present evidence that eviscerates their inerrantist beliefs. Since Heaven and Hell are fictions of the human mind, I am content to let knowledge do her perfect work. I know that most Evangelicals will never abandon their faith (the one true faith), but some will, so I am content to continue fishing for the minds of women and men. Using reason and knowledge is the only way I know of to make the world a better place. Part of making the world a better place is doing all I can to neuter Fundamentalist beliefs. Inerrancy is one such belief.

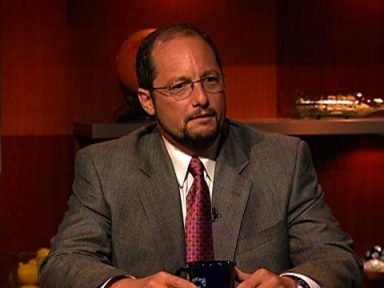

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.