Erica Komisar, a licensed clinical social worker in New York City, writes:

Nihilism is fertilizer for anxiety and depression, and being “realistic” is overrated. The belief in God—in a protective and guiding figure to rely on when times are tough—is one of the best kinds of support for kids in an increasingly pessimistic world. That’s only one reason, from a purely mental-health perspective, to pass down a faith tradition.

I am often asked by parents, “How do I talk to my child about death if I don’t believe in God or heaven?” My answer is always the same: “Lie.” The idea that you simply die and turn to dust may work for some adults, but it doesn’t help children. Belief in heaven helps them grapple with this tremendous and incomprehensible loss. In an age of broken families, distracted parents, school violence and nightmarish global-warming predictions, imagination plays a big part in children’s ability to cope.

I also am frequently asked about how parents can instill gratitude and empathy in their children. These virtues are inherent in most religions. The concept of tikkun olam, or healing the world, is one of the pillars of my Jewish faith. In accordance with this belief, we expect our children to perform community service in our synagogue and in the community at large. As they grow older, young Jews take independent responsibility for this sacred activity. One of my sons cooks for our temple’s homeless shelter. The other volunteers at a prison, while my daughter helps out at an animal shelter.

Such values can be found among countless other religious groups. It’s rare to find a faith that doesn’t encourage gratitude as an antidote to entitlement or empathy for anyone who needs nurturing. These are the building blocks of strong character. They are also protective against depression and anxiety.

In an individualistic, narcissistic and lonely society, religion provides children a rare opportunity for natural community. My rabbi always says that being Jewish is not only about ethnic identity and bagels and lox: It’s about community. The idea that hundreds of people can gather together and sing joyful prayers as a collective is a buffer against the emptiness of modern culture. It’s more necessary than ever in a world where teens can have hundreds of virtual friends and few real ones, where parents are often too distracted physically or emotionally to soothe their children’s distress.

I wanted to scream after I read Komisar’s article. I thought, “are you really this stupid?” “Did you bother to talk to atheist parents and their children?” “Are you really equating atheism with nihilism?” “Are you really advocating lying to children about one of the most profound issues we humans struggle with — death?” “Are you really suggesting that parents pass on a faith tradition to their children as some sort of inoculation against depression?” “Are you aware of the psychological damage caused by religions, especially fundamentalist religions such as Evangelicalism, Islam, conservative Catholicism, and right-wing Jewish sects?” “Are you aware of the fact that many atheists are humanists, and humanism provides a moral, ethical, and social framework for them?”

Komisar would have us believe “in an individualistic, narcissistic and lonely society, religion provides children a rare opportunity for natural community.” Natural? Are you kidding? What’s “natural” about eating the body of Jesus and drinking his blood? What’s “natural” about believing God is three, yet one; that the universe was created 6,024 years ago; that dead people can come back to life; that the Bible stories about a miracle-working man named Jesus are true; that people can be roasted in a furnace and not be harmed; that the earth was covered with water just a few thousand years ago; that the Holy Spirit lives inside of people and is their teacher and guide; that premarital sex, homosexuality, and a host of other human behaviors are sins, and unless forsaken, will bring the judgment of God down upon their head? Sorry, but Komisar really didn’t think the issue through before she wrote her article for the Wall Street Journal.

What more troubling is the fact that Erica Komisar is a licensed social worker and counselor. I suspect her approach to religion is very much a part of her counseling methodology. I wonder what Komisar would say to depressed atheists or agnostics? Go to church? Find a religion to practice, even if you have to fake believing? Jesus F. Christ, such thinking is absurd.

Now to the question, “should parents lie to their children about death?” Komisar suggests that parents use religious language to comfort children about death, either their own or that of their loved ones. Better to lie to children about where recently departed grandma is than to tell them the truth: Grandma is dead and you will never see her again. Cherish the memories you have of her. Look at photographs of her, reminding yourself of the wonderful times you had with her.

Komisar would rather children live in blissful ignorance than face reality. Grandma is in Heaven with Gramps. Grandma is running around Heaven with her loved ones. Grandma is no longer suffering. She is right beside Jesus, enjoying a pain-free existence. Bollocks!

While I can see avoiding the subject of death with young children, by the time they are in third or fourth grade, they should be ready to face the realities of life. People die. Some day you will die. That’s why Grandpa Bruce wrote this on his blog:

If you had one piece of advice to give me, what would it be?

You have one life. There is no heaven or hell. There is no afterlife. You have one life, it’s yours, and what you do with it is what matters most. Love and forgive those who matter to you and ignore those who add nothing to your life. Life is too short to spend time trying to make nice with those who will never make nice with you. Determine who are the people in your life that matter and give your time and devotion to them. Live each and every day to its fullest. You never know when death might come calling. Don’t waste time trying to be a jack of all trades, master of none. Find one or two things you like to do and do them well. Too many people spend way too much time doing things they will never be good at.

Here’s the conclusion of the matter. It’s your life and you best get to living it. Some day, sooner than you think, it will be over. Don’t let your dying days be ones of regret over what might have been.

I have six children, ages 26 to 40, and twelve grandchildren, aged 18 months to nineteen. I dearly love my family. If 2019 has taught them anything, it is this: Mom and Dad and Nana and Grandpa are feeble, frail humans. Both of us faced health circumstances that could have led to our deaths. Shit, we are in our sixties. Most of our lives are in the rearview mirror. Even if we live to be eighty, seventy-five percent of our lives are gone. Saying that our best days lie ahead is nothing more than lying to ourselves. We remember our twenties and thirties. We remember the days when we had the proverbial tiger by the tail. Those days are long gone. My mom died at age 54. Dad died at age 49. Polly’s parents are in their eighties. Both of them are in poor health and will likely die sooner than later. I mean, a lot sooner than later. It is insane for my adult children to lie to their progeny about their grandparents and great-grandparents. I want my grandchildren to know that I love them and that I wish I had fifty years of life left so I could watch their children’s children grow up. But, I don’t. When I come to their basketball game, play, band concert, or school program, I do so because I want them to have good memories of me. I want them to remember that I was there for them. I know that the ugly specter of death is stalking me, and one day my children will be forced to tell their children that Grandpa is dead. I don’t want them lying to their children about my post-death existence. I plan to be cremated and have my ashes scattered on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan — a place where the love of my life and I experienced a “perfect” day. Hopefully, being involved with the disposal of my final remains will impress on my grandchildren the importance of living each day to its fullest. Death, when we least expect it, comes for us one and all. Better to face this fact and live accordingly than to believe that Heaven and eternal bliss awaits us after we die.

Let me conclude this post with an excerpt from a 2018 NPR article titled Teaching Children To Ask The Big Questions Without Religion:

Emily Freeman, a writer in Montana, grew up unaffiliated to a religion . . . She and her husband Nathan Freeman talked about not identifying as religious — but they didn’t really discuss how it would affect their parenting.

“I think we put it in the big basket of things that we figured we had so much time to think about,” Emily joked.

But then they had kids, and the kids came home from their grandfather’s house talking about Bible stories.

Nathan acknowledges that this came from a good place, and his father was acting in concern. “He feels like these lessons encapsulate a blueprint for how to move through life. And so of course, why wouldn’t we want our children to have those lessons alongside them as they travel through the world?”

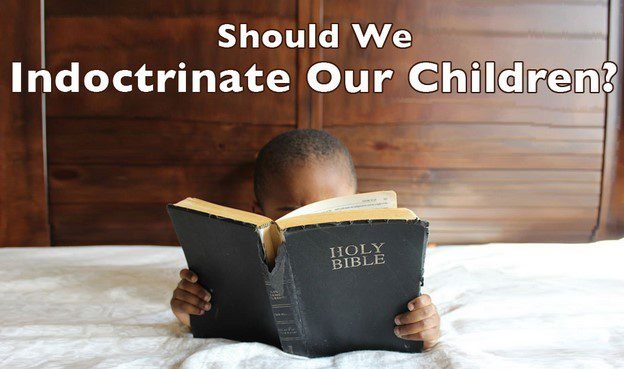

But while Nathan and Emily wanted their kids to learn about love and compassion, they didn’t want them to hear Bible stories. When the boys were so young, the certainty of those stories felt like indoctrination.

“They trust everything that you tell them,” Emily observed. “About how their body works, about how the world works. How a cake suddenly becomes a cake from a bunch of ingredients on the counter — everything!”

….

People often, as you may expect, would leave religion during the rebellious teenage years — [ professor Christel] Manning says the baby boomers were the first generation to do this in fairly large numbers. But about half of them went back after they got married.

“If I’m single, and I have a certain spiritual or secular outlook, that’s my personal thing,” Manning explains. “But when I form a family, then there are other people who become stakeholders in this process.”

In addition to the spouses themselves, there are often parents and other family members who want influence, and kids who want answers. These are some pretty big questions — kids are asking about life and death, right and wrong, and who are we?

The answer to these questions was often found in religion. But this isn’t holding true for the current generation of parents. They aren’t returning to religious affiliation — or affiliating in the first place.

In the Freeman family’s case, did the grandparents need to be worried? According to Manning, the data on growing up without religion are mixed. Some studies show that children growing up in a faith community experiment less with drugs and alcohol and juvenile crime. And some show that kids raised without religion are more resistant to peer pressure, and more culturally sensitive.

“But,” as Manning points out, “and this is a big but — we don’t know if it’s religion that benefits the children, or if it’s just being part of an organized community, with other caring adults that regularly interact with your child.”

Manning — who raised her own child without religion — notes that there are lots of ways to raise a child to be moral and religion is only one of them.

“I’d say from what we know now, both a religious and secular upbringing can have both benefits and risks for children.”

For some unaffiliated parents, like Emily Freeman, raising children outside of a definitive religious construct can be very valuable, by empowering them in not knowing.

….

For some people, religion can provide these answers. For others, it’s a sacred space to explore not knowing. Parents like Emily Freeman try to help their kids find their own voice in the conversation. About belief, about what’s right, about their values as a family.

“They don’t spend all day wondering why zebras have stripes. We just look it up on the phone. And boom — wonder, done!” laughs Freeman. “So I love this idea of giving them open-ended, unanswerable questions. And saying, who knows? And people you love can believe different things than you do, and that’s OK.”

….

Are you an atheist, agnostic, or non-religious? What have you taught your children about death? Do you think it is okay to lie to children about death? Please share your deep thoughts and advice in the comment section.

About Bruce Gerencser

Bruce Gerencser, 62, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 41 years. He and his wife have six grown children and twelve grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist. For more information about Bruce, please read the About page.

Are you on Social Media? Follow Bruce on Facebook and Twitter.

Thank you for reading this post. Please share your thoughts in the comment section. If you are a first-time commenter, please read the commenting policy before wowing readers with your words. All first-time comments are moderated. If you would like to contact Bruce directly, please use the contact form to do so.

Donations are always appreciated. Donations on a monthly basis can be made through Patreon. One-time donations can be made through PayPal.

We haven’t had any people deaths since the kid was born, but we have had three dog deaths in the few years since we deconverted. (Don’t have multiple dogs all about the same age.) We didn’t lie to her. There was no talk of a rainbow bridge, etc. Just told her it was ok to be sad – that we were too – and we can always look at pictures and talk about them and remember the times we had with them. I plan on doing the same when, non-existent God help me, her grandparents start passing away. (Suspect going to a shelter to get a new one won’t be a part of the healing process in that case though…) Anyway, I think she understands as much as possible for her age that we are purely physical creatures, that death is permanent, and that it comes for us all.

Niedawno zmarł nasz kot. To była dobra okazja aby z naszą czteroletnią córką porozmawiać o śmierci. Powiedzieliśmy jej prawdę. Pocieszające było dla niej, że może ukochanego kota wspominać.

Translation:

Our cat has recently died. It was a good opportunity to talk to our four-year-old daughter about death. We told her the truth. It was comforting for her that she could remember her beloved cat.

I think there are different ways for the non-religious, agnostic &/or atheist to approach death with children. Lying is not one of them in my opinion. I actually wonder if lying isn’t the worst thing you can do to children because I think they are smarter than the so-called experts when it comes to recognizing someone is not telling the truth. It also depends perhaps on the child’s age, personality and development. Some two year olds can get it. Some six year olds can’t. Speaking in general terms.

Young children can see there’s a difference between the health and age of their parents and that of their grandparents. Being honest about that all the way along for children who are curious should be par for the course.

Great-Grandma needs some help right now. She hasn’t been feeling well. She loves you so much. We love her so much. Remember that time we laughed with great-grandma and had so much fun eating pizza? The child gains an awareness of reality and every day life.

Later: Do you remember our talks about great-grandma and how much we love her. Well grandma’s body got very weak and tired and it stopped working. We aren’t going to get to see her again and that feels sad. We’re really going to miss her but we were so lucky we got to know her, hug her and play with her. How special she was. Some children may pick up on your sadness before their own and want to comfort you before you even get to comforting them. 🙂 With some children you can say, “Do you need a hug?” And with their permission offer one. Some children won’t want that hug yet as they are still processing. Yet, you can stay present with them. It’s okay to take cues from the child(ren).

Provide pictures or videos if some children want to see them. If pictures have been around their whole lives this makes a transition easier.

Reminding children of the fun, the love, the experiences keeps the ancestor’s alive. Their bodies aren’t here anymore but our memories of them will always be with us because of our love for them.

Stuff like that. Based on some personal experience.

As for the grandchildren we have that are being raised with heaven and hell, when one of them says to us, “He’s in heaven right?” Our response is, “Yes, he died and he’s not here anymore.” This way we are not interfering with the Catholic upbringing but we are also not “lying” and dishonouring our position nor their parents.

There is no need to continue disrespecting children when we throw off the blinders of ‘belief’. What matters is connection with our kids, being with them and opening our hearts to their individual being. I think Zoe’s examples of connection fit the bill because in them I see first and foremost, utter love and respect, simple human caring. My grandparents and parents all believed in the Christian god and all talked about being together again in glory and so forth. When my maternal grandmother died, she had long before wished it, to be with her husband in heaven. When my mom died not long back, my dad was well into senility and he asked me, more in confirmation than as a question, “Is mom in heaven now?” He did not wish to call death simply that because his belief system put heaven in death’s place. He managed to let go of his breath finally within a month or so of mom’s departure from this life.

When I finally exited Christianity, I felt such peace in simply telling the truth and not lying anymore. I will not lie to my children and I try not to lie to anyone. I am a pretty old guy now and I am not always successful in being truthful entirely but I continue to enjoy it when I am able!

I learned about death when I was about six. I was rummaging around on my parents’ bookshelves looking for something interesting to read, selected a parenting book, and discovered a chapter entitled “How to tell your child about death.”

After having the 1960’s equivalent of a “Wait, what?” moment, I simply expanded my worldview to incorporate the new information.

And I distinctly do not remember anything about lying to kids with some religious fable.

Public libraries have children’s books on many subjects from different points of view.

We were just honest with our kids when they asked. We said that so-and-so’s body didn’t work anymore and they died and aren’t here and aren’t returning, we will miss them, and it’s ok to be sad. That we don’t know what happens to the thoughts, memories, etc, of a person after they die. Some people believe in heaven, reincarnation, etc, and we believe that death is just the end. My daughter said one of her friends said that my daughter’s concept that people just die and that’s the end is probably true, but she can’t bear to think she won’t see loved ones in an afterlife. My daughter told her that’s why it’s important to spend time together now.

I don’t think lying to kids about it is right. There are ways to explain uncomfortable things kindly and compassionately. My kids are young adults and don’t seem harmed by growing up not believing in an afterlife.

I forgot to add that my daughter always tells her family and close friends “I love you” whenever they part because she says you never know of it’s the last time you get to be together and she wants to make sure they all know she loves them.

In a 4-D cosmos of Space-Time, death is quite natural. It is permanent and quite final. It does sound like nihilism because that little tidbit of information is only a fragment of what may be going on in reality itself. Atheism is a “ belief” that we exist in a 4-D reality ONLY. There is nothing else. Math is the very basis of our secular belief system because it underwrites all physics. Physics, not religious belief, determines our reality. There is a sound “belief” in the afterlife by many humanists. It is the ONLY type of afterlife that is dismissed out of hand by every religion on the planet because it is not written in the word of Man. It is written in Mathematics only. That’s where our “faith” really lies. No known math rules out backwards Time travel. Physics tackles this. Wormholes require the exotic physics of Casimir energy, black-holes, and extraordinary levels of energy. The difference between math and physics is that Physics “makes” math real. Mathematics provides all possible doors that one can walk through to the “other” side. Physics however is the tool that is used to “pick” that door AND therefore bring it into our reality. This is what we should be teaching our children. If you can dream it, and, the Math allows it, then bring in the physics. In religion, it is often said … “Man Cannot Save Himself”. Teach your child one thing …. “Prove Them Wrong!!!!”

I don’t have kids, and I was a believer until I was 40. I can’t imagine my childhood without belief in Jesus, heaven, etc. And my Grandmother is primarily responsible for what I believed.

Nobody knows with any certainty what happens at death. I believe it’s the end, but if I had kids who were being taught otherwise by my family, I wouldn’t make waves. I would just say “maybe” and let them decide for themselves when old enough to confront the nature of unfairness, injustice, and horrible happenstance in the world.

I knew my father believed in evolution, and while I viewed him with a smug, holier than thou attitude, that all worked itself out in time. Now he’s a believer, and I’m not.

I believe in Newton’s Second Law of Thermodynamics: Energy can neither be created nor destroyed. Therefore, in some way the energy our bodies creates is retransformed by the universe at the moment of our deaths, so we do have a type of immortality which does continue. Of course, it is not human; but, that should not matter.

Not only does energy persist, but the matter in our bodies eventually finds new gigs. I’ve got some carbon atoms that aspire to be a dahlia one day. 😀

Julia M. Traver, I’m an atheist, but I actually agree with this and have felt this way for a long time. It’s comforting to think that one day I will return to the vastness of the universe and continue to be a part of it forever. Meanwhile I hope those I leave behind will have fond memories of me and maybe even feel some joy when they think or speak of me.

And no – I don’t agree with lying to children about death. The author of the article is way off base and it seems she uses her profession to spread her religious views.

If you don’t believe in an afterlife, I don’t think you should lie to your children and tell them that Grandpa is in Heaven. I do think, though, that you should admit that you don’t know what happens after people (or animals) die, but it’s OK to hope that Grandpa (or Mittens) is in Heaven, and maybe you will see him again when you’re dead, too. It’s not lie–because you don’t actually know–and it leaves a child something to hope for. They may resolve the issue in their own minds when they’re older, or not.

I never had children so I can’t comment from that point of view, but I have to say that one thing my parents got right was having the proper attitude about death. I was exposed to it at a young age and IIRC they did not overly sugar-coat it with things like, “they’re in a better place,” and such. My dad was a church goer his entire life; my mom does not attend, but if you asked her she’d say she was a believer (they divorced when I was 17 in 1974). Anyway, I was always aware of what death was and taught not to fear dead relatives or other dead people. It was made clear that this was part of life and that it would happen to us all, hopefully at an old age, however sometimes young people died too. Yeah, we go the ” the lord works….” explanation, but not overly so. It was more like, ‘these people were here, now they’re gone, they live in your hearts and memories, but it is okay to be sad.’

As someone whose mom, 2 weeks before she died, admitted to lying her whole life about everything, I can readily say, No! Never lie to your kids about anything. I know this isn’t quite the same as the death issue, but once you start lying to your kids, and they find out, it will destroy your relationship. She died in 2012, and I still cannot forgive her for her lies. Parents should explain whatever their own belief system is, and kids can make their own choices when they grow up. Even if they disagree, they will know their parents are not lying hypocrites.

Our attitude toward telling our daughters about things like Santa and the Tooth Fairy, and other myths that a lot of children are taught to believe, was, “If you lie about that, you’ll lie about other things, too.” We taught them about the traditions around Santa, but admitted that we were the ones giving the gifts, in the tradition of. St. Nicholas of Myra. Then, since they were in on it, always labeled at least one gift “From Santa.” And we cautioned them that some kids’ parents wanted to pretend, and not to tell other children that there was no Santa, except their relatives.

My parents were pretty matter of fact about death. When our dog died they said that “Barnaby was old and sick and just couldn’t go on any longer, he’s at peace now and we can remember the fun times.” For whatever reason I never cared that much about that dog, so life went on. I was a sixth grader the first time a loved one died, both my grandfathers were gone before I was born. My maternal grandmother was senile and I wasn’t close to her for that reason. So what registered for me more was the strain between my mother and her sister and my mom’s vocal, low key dismay over the open casket and her palpable relief when I said “It doesn’t even look like Nana Donnie!” Nobody said anything about heaven, only ‘peace’ and that was ok with me.

They raised us with a paper thin veneer of milquetoast protestant belief. One of my sisters needed more and became a Methodist they neither stopped her nor encouraged her and it was the same for me.

I simply told my children that grandpa died, then that nana died and they coped reasonably well with the proceedings. We raised them with an understanding that some religious practices carried cultural values that matter. Most of these are because my husband’s family are Jewish and the culture matters to them even though they do not believe in God.

We didn’t do Santa but we did warn our kids that other children did believe and it was not up to them to appraise their classmates of the harsh realities of life.