Years ago, there was quite a dust-up on a previous iteration of this blog over a guest post written by a former Evangelical man named Ian. Ian posited that Christian claims of persecution were grossly overstated; and that many persecution claims were not persecution at all. I agreed with Ian’s assessment, and have continued to do so to this day. One man, a Greek Orthodox Christian, took umbrage with my position on persecution, alleging that I supported the slaughter and murder of Christians. This claim, of course, was patently false. This man went far and wide on the Internet trying to smear me, without success. An Internet search today revealed he no longer has a blog and his accusations have disappeared from the web.

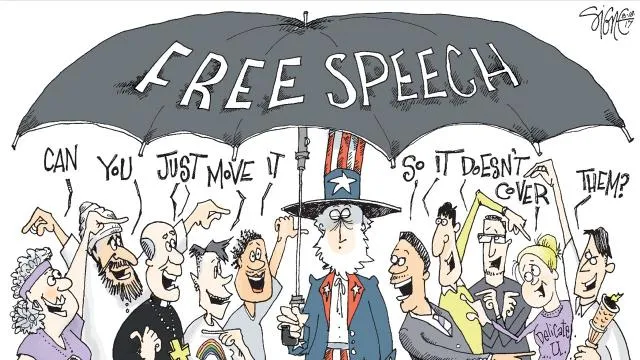

Today, I intend to revisit this issue. This post will likely infuriate Evangelicals, especially those who believe that Christians are increasingly persecuted and martyred. (Dr. Candida Moss’ book, The Myth of Persecution, is a good read on this subject.) Listen to some Evangelicals and you’d think Christians are being slaughtered left and right. And even here in the United States, Evangelicals, in particular, are being persecuted for their faith. While it is certainly true that there are individual incidents of persecution in the U.S., to suggest that the government, Joe Biden, Democrats, atheists, agnostics, and other non-Christians are “persecuting” meek, mild, loving, kind, self-effacing Evangelicals is untrue. And if you object to my claim, please provide evidence for your assertion in the comment section.

Ask the average American to define “social contract” and they will give you that deer-in-the-headlights stare. Most people are clueless that the underlying principle governing their day-to-day lives is a social contract.

Wikipedia defines “social contract” this way:

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it is a core concept of constitutionalism, while not necessarily convened and written down in a constituent assembly and constitution.

Social contract arguments typically are that individuals have consented, either explicitly or tacitly, to surrender some of their freedoms and submit to the authority (of the ruler, or to the decision of a majority) in exchange for protection of their remaining rights or maintenance of the social order. The relation between natural and legal rights is often a topic of social contract theory.

….

The central assertion that social contract theory approaches is that law and political order are not natural, but human creations. The social contract and the political order it creates are simply the means towards an end—the benefit of the individuals involved—and legitimate only to the extent that they fulfill their part of the agreement. Hobbes argued that government is not a party to the original contract and citizens are not obligated to submit to the government when it is too weak to act effectively to suppress factionalism and civil unrest.

People groups gather into communities, states, and countries. When doing so, there is a need for order. Laws are passed to give structure and legal codification to governing entities. As citizens, we enter into a social contract with the government and each other, agreeing to obey the law and play by the rules under threat of punishment if we don’t. Laws govern every nation-state. Of course, the laws differ from country to country, state to state, and city to city. What may be criminal in one country, state, or city is legal in others. Generally, citizens play by the rules of their respective governing authorities, and when visiting other countries, they agree to play by their rules. When in Rome, the old saying goes, do as the Romans do.

The United States is a nation of laws, much like our mother, Britain, before us. As a Republic, citizens, through their elected representatives, enact or change the laws by which they are willingly governed. We may disagree with certain laws, but until said laws are changed, we are obligated to obey them. And when we don’t, we face punishment for breaking the law — be it murder, rape, or driving without a valid license.

Years ago, I was a music thief. I accumulated tens of thousands of ripped and downloaded mp3s. I had moral and philosophical reasons for doing so — my music, I can do with it what I want — but I knew I risked losing my Internet service or being fined for breaking the law. I continued to download music, knowing, at any moment, I could be caught and punished for my behavior. The same goes for speeding. The speed limit on the freeway is 70 mph. Polly never drives 70. She always speeds along at five to ten miles over the speed limit. If pulled over by a highway patrolman, she would likely receive a ticket — justifiably so. To quote one of the world’s greatest detectives, Tony Baretta, “Don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time.”

Every six weeks or so, we drive to Michigan so I can buy cannabis. Presently, doing so is against the law, though it is unlikely that I will be arrested. And if I am, the violation is a misdemeanor. I am willing to risk breaking the law for the physical benefits I gain from cannabis use. Reducing chronic pain is more important to me than the risk of being busted for buying THC-infused gummies. All of us have been, at one time or another, and to one degree or another, lawbreakers.

Our social contract governs how we live our day-to-day lives, especially when in contact with other people. Things I may do in the privacy of my own home can be considered crimes when done in public. For example, at 4:00 am I may painfully, slowly shuffle to the bathroom to pee — sans clothing. I sleep in the nude, as I have my entire adult life. Now, thanks to damage to my lower back, I no longer have bladder and bowel control. When I have to go to the bathroom, it’s now . . . I mean right now. The difference between making it to the toilet and a mess is a matter of seconds or feet. I don’t have time to put clothes on first (which is fine since no one is up but me at 4:00 am). However, I would never use a public restroom without clothing on. Why? We have laws governing public decency and nudity. Think for a moment of all the things we do in the privacy of our homes that we can’t do in public. Want to have sex with your spouse, or significant other, or a pick up from the local bar at your home? Have at it. Couches, beds, floors, tables, or desks are places people are known to use for sex. However, having sex in public is illegal. Have my partner and I had sex outdoors or in a car — back when we were young, virile gymnasts? I’m not going to say one way or another. 🙂 That said, if we did take a roll in the sand on a secluded beach under a moonlit night, and a park ranger found us, we likely would have been arrested. That’s the social contract we have with one another. Want to have sex? Do it in the privacy of your home. Want the thrill of having forbidden sex — and who doesn’t? That’s your right, just as long as you know that if you are caught you could be arrested. I can say this as a sixty-seven-year-old man — some experiences are worth the risk. 🙂

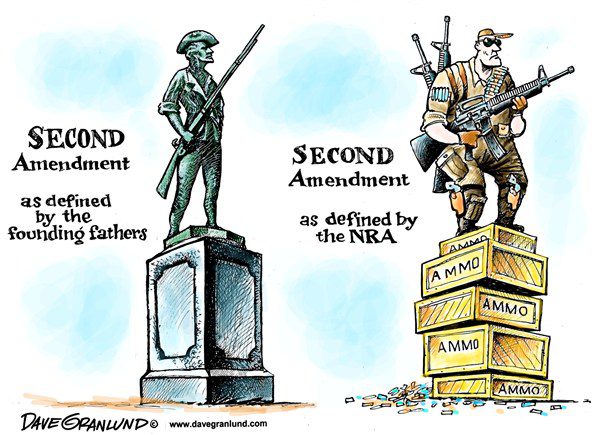

While Evangelicals will generally agree with the premise of a social contract, they add a caveat. Yes, God commands Christians to obey the laws of the land, but only if doing so doesn’t break the law of God (as interpreted by them). If a human law violates the law of God, Christians are duty-bound to disobey. Thus, Evangelicals can justify all sorts of criminal behavior, be it murdering abortion doctors, illegally picketing abortion clinics, smuggling Bibles into Communist/Muslim/Hindu countries, or being missionaries under the guise of being English teachers in foreign countries.

Sadly, many American Evangelicals think that when they travel to other countries to evangelize people, the laws governing said behavior don’t apply to them. They wrongly think that U.S. law with its strong First Amendment protections and religious freedoms applies universally. It doesn’t. When in other countries, the laws of those countries apply. Thus, when an Evangelical illegally distributes Bibles, religious literature, or proselytizes non-Christians, they are breaking the law. What God or the Bible says is immaterial. Just because Evangelicals believe they should obey God over men doesn’t mean that nation-states must acquiesce to their peculiar religious beliefs. Thus, when arrested, they aren’t being persecuted. They are lawbreakers. Remember, when in Rome do as the Romans do. If a country’s law prohibits proselytization, then doing so anyway is lawbreaking, and not persecution. Evangelicals are free to risk their safety and freedom to evangelize others where proselytization is forbidden, but don’t scream persecution if caught. To quote Tony Baretta once again, Don’t do the crime, if you can’t do the time. Don’t hand out Bibles, tracts, or witness to people if you aren’t willing to be arrested and imprisoned for your crimes. Like it or not, many nations don’t have religious freedoms as we do in the United States. Until said laws change, breaking them could result in arrest. It is NOT persecution when you are arrested for breaking the law. Self-righteous, arrogant Americans wrongly think “When anywhere in the world, I have a right to do whatever we do in the United States.” This approach, of course, will land your Jesus-loving ass in jail.

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.