Guest Post by MJ Lisbeth

A few days ago, I wrote about the report on sexual abuse in French Roman Catholic churches. While I was, naturally, recalling my own experiences of sexual exploitation by a priest, and of living in France, what motivated me to write the article was a conversation with someone I met only recently and, to my knowledge, knows nothing about the experiences I’ve described in other essays and articles.

She is a professor of English and African-American studies in a nearby college. While growing up, she shuttled between the US and Jamaica, where she was born. She, therefore, has a visceral understanding as well as an academic knowledge of something that’s become a punching bag for religious and political conservatives in this country: Critical Race Theory.

While we mentioned it, and one of us remarked that those who rail against it have absolutely no idea of what it is, we didn’t talk about it in depth. Rather, a seemingly unrelated topic led us into a conversation about, among other things, how our accomplishments have “drawn targets on our backs” for those who wanted to discredit us or, worse, get us fired on spurious charges—and how the very rules we followed were used against us for following them.

“You have paid for what you know,” I sighed. “And I’m not talking about your college and grad school tuition.”

“And I still am.” I nodded. “And so are you,” she added.

Of course, she could have been talking about any victim in the French report or others like it. People who are sexually abused or assaulted, or suffer any other kind of trauma, by definition, spend the rest of their lives paying for what was done to them. Those psychic wounds—and, too often, physical debilitations—are intensified, and passed on generationally (and, according to recent research, genetically) through the racism, sexism, homophobia and other prejudices encoded in our laws, embedded in our institutions and, most important, enmeshed in the lenses through which people see their world and act on it.

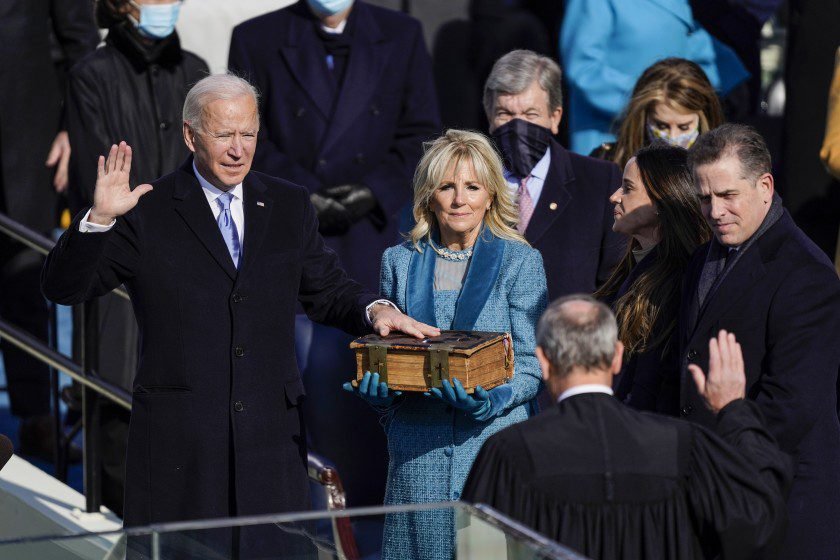

Critical Race Theory, as I understand it, posits that race is a social construct and, therefore, racism is a product, not only of individual prejudices and actions, but also something woven into legal systems and policies. Thus, the fact that we’ve had a Black (actually, multi-racial) President, and African-American athletes and entertainers are among the wealthiest people in America, no more validates the claim that “racism is over” (a claim I’ve heard, not only from conservatives, but from people even further to the left than I am) than defrocking a few priests—or sentencing them to “prayer and penance”—will eradicate clerical sexual abuse.

The French report, and others, say as much: Nothing less than a reform of, not only the way rogue priests and deacons are disciplined, but of the very systems that have enabled them to commit their crimes, is needed. For one thing, there needs to better screening and monitoring of clerics-in-training, and young clerics. As an example, a priest (not the one who sexually abused me) in my old church was defrocked—years after accusations that he sexually exploited boys in the parish were verified. I’m glad that he was cast out of the priesthood (my abuser died before I, or any of his other victims, spoke of his deeds), but he really shouldn’t have been a part of it in the first place: My morbid curiosity led me to discover that before he was “transferred” to our parish from another, he’d been kicked out of a seminary for sexual misconduct. That didn’t keep him from enrolling in—and graduating from—another seminary!

Just as the Roman Catholic Church, and other religious institutions, need to prevent predators from becoming prelates, it also needs to dismantle the systems and structures that allow officials, from the Pope on down, to shield perpetrators from justice. Local priests are transferred from one parish, or even diocese, to another when parishioners complain about their behavior; after Bernard Francis Law resigned as Archbishop of Boston and moved to Rome, Pope John Paul II appointed him as the Archpriest of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, which made him a citizen of Vatican City—and thus immune to prosecution by US authorities.

Then again, even when perpetrators are called to account for their crimes, it’s often a hollow victory: Because victims, for a variety of reasons, don’t talk about their sexual abuse for decades after they experienced it, by the time a priest is accused, the accounts are verified and the wheels of justice grind along, the perfidious prelate is very old—or dead, as my abuser was by the time I or any of his other victims spoke up.

Cases like Law’s are cited as reasons why systemic change, while needed, is not enough. More than a few people, including commenters on my previous post, have suggested that what underpins the system—the Bible itself—is the root of the problem. I would agree, as the Abrahamic religions, in all of their iterations from the Taliban’s version of Islam to the most liberal Episcopal or Reform Jewish congregation–is premised on gender, racial, and other social hierarchies specified in everything from the Books of Exodus and Leviticus to the letters of Paul. Bringing in a mixed-race transgender minister, and rooting out an individual paedophile, can do no more to change the inherent biases of the Bible and the institutions based on it than choosing another Black President or CEO, or driving out another individual racist, will destroy the system that perpetuates intergenerational traumas and inequalities—or getting rid of a few rogue cops or arresting a few drug dealers or users will eradicate the draconian laws and unjust social conditions that fuel the demand for, and business in, banned substances.

Until structures, systems, and institutions based on arbitrarily-defined groups of people and designed to protect or punish some of those groups (just as arbitrarily chosen) are, not reformed, but dismantled, their victims will continue to pay for what they are forced to learn—and what the perpetrators can’t, or won’t, understand. The woman I mentioned at the beginning of this essay knows as much.

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.