I grew up in churches that believed Christians were to give their hearts, souls, and minds to God. Followers of Christ were implored to lay their lives on the altar and give everything to Jesus. The hymn I Surrender All aptly illustrated this:

All to Jesus I surrender,

All to Him I freely give;

I will ever love and trust Him,

In His presence daily live.Refrain:

I surrender all,

I surrender all;

All to Thee, my blessed Savior,

I surrender all.All to Jesus I surrender,

Humbly at His feet I bow;

Worldly pleasures all forsaken,

Take me, Jesus, take me now.All to Jesus I surrender,

Make me, Savior, wholly Thine;

Let me feel the Holy Spirit,

Truly know that Thou art mine.All to Jesus I surrender,

Lord, I give myself to Thee;

Fill me with Thy love and power,

Let Thy blessing fall on me.All to Jesus I surrender,

Now I feel the sacred flame;

Oh, the joy of full salvation!

Glory, glory, to His Name!

“I surrender my life to you, Jesus,” I often prayed. “I’ll say what you want to say, do what you want me to do, and go where you want me go.” Jesus commanded his followers to take up their cross and follow him. Those who were unwilling to do so were not his disciples. The book of First John had this to say about what Jesus expected of people who said they were Christians:

And hereby we do know that we know him, if we keep his commandments. He that saith, I know him, and keepeth not his commandments, is a liar, and the truth is not in him. (1 John 2:3,4)

Love not the world, neither the things that are in the world. If any man love the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world, the lust of the flesh, and the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life, is not of the Father, but is of the world. And the world passeth away, and the lust thereof: but he that doeth the will of God abideth for ever. (1 John 2:15-17)

Whosoever abideth in him sinneth not: whosoever sinneth hath not seen him, neither known him. Little children, let no man deceive you: he that doeth righteousness is righteous, even as he is righteous. He that committeth sin is of the devil; for the devil sinneth from the beginning. For this purpose the Son of God was manifested, that he might destroy the works of the devil. Whosoever is born of God doth not commit sin; for his seed remaineth in him: and he cannot sin, because he is born of God. In this the children of God are manifest, and the children of the devil: whosoever doeth not righteousness is not of God, neither he that loveth not his brother. (1 John 3:6-10)

My little children, let us not love in word, neither in tongue; but in deed and in truth. (1 John 3:18)

Beloved, let us love one another: for love is of God; and every one that loveth is born of God, and knoweth God. He that loveth not knoweth not God; for God is love. (1 John 4:7,8)

For whatsoever is born of God overcometh the world: and this is the victory that overcometh the world, even our faith. Who is he that overcometh the world, but he that believeth that Jesus is the Son of God? (1 John 5:4,5)

We know that whosoever is born of God sinneth not; but he that is begotten of God keepeth himself, and that wicked one toucheth him not. (1 John 5:18)

If these verses are taken literally, one thing seems clear: most people who profess to be Christians are what some preachers call “professors and not possessors.” These people have prayed a prayer and embraced cultural Christianity, but they know nothing of True Salvation®. These verses, taken at face value, show that God sets an impossible standard of living.

Evangelical pastors have all sorts of explanations for these verses:

- There are two classes of Christians: spiritual and carnal. Both are saved, but carnal Christians still live according to the dictates of the “flesh.” Carnal Christians are “babies” in Christ. Readers might remember that this is how some Trump-supporting Evangelicals justified the President’s un-Christian lifestyle. He is just a babe in Christ who needs to mature in the faith, these pastors said. Thus, spiritual people will live according to these verses, and carnal Christians won’t.

- People become Christians by believing a set of propositional truths. What truths must be believed vary from sect to sect. After they are saved, these newly minted Christians are encouraged to attend church every time the doors are opened, tithe, pray, give offerings above the tithe, study the Bible, give to the building fund, and follow the church’s teachings. Not doing these things will result in a lack of blessing from God in the present and a lack of future rewards in Heaven. Once people mentally assent to the gospel and pray to Jesus for the forgiveness of sins, they are forever saved. (This is why some Evangelicals believe I am still a Christian.) These verses are a lofty goal Christians should strive to achieve, but if they don’t, no worries, they are still saved.

- Saved people have two natures: the spirit and the flesh. The spirit cannot sin, but the flesh can. The verses that talk about not sinning refer to the spirit, not the flesh. Christians still sin in the flesh, but the spirit is sin-free.

- These verses must be interpreted in ways that give them nuance, harmonizing them with the rest of Scripture. It’s hard to not conclude with this approach to these verses, that what pastors are saying is that God didn’t mean what he said.

- These verses are to be taken literally. The Bible commands us to die to self, crucify the flesh, etc. Salvation is conditional. Do these things and thou shalt live. Don’t do these things and you will perish and go to hell. No one can know for sure if he or she is saved. Calvinists say that followers of Christ must endure to the end to be saved. And even then, God, on judgment day, will be the ultimate judge of whether a person’s good works reached the enter into the joy of the Lord (Heaven) level.

- Some Christians believe that the Holy Spirit takes up residence in people’s lives the moment they are saved, but that there is a separate, special baptism or infilling of the Spirit that can take place at a later date. Often called being baptized with Spirit or a second definite work of grace, those who receive this second filling of the Holy Spirit live lives wholly consecrated to God. Some Christians believe in what is called entire sanctification — a state of sinless perfection. People who are entirely sanctified no longer sin. When doubters point out certain less-than-Christian behaviors by the sanctified, they are often told these bad behaviors are mistakes, not sins.

I spent much of my Christian life seeking to love Jesus with all my heart, soul, and mind. I didn’t know, at the time, that there’s no such thing as a heart or a soul, but I took the commands to live this way as saying that I was to give everything to Jesus. I was to die to worldly pleasures and desires. I was to seek first the kingdom of God and His righteousness. My desires, wants, and needs didn’t matter. All to Jesus I surrender, all to Him I freely give, I told myself. My life belonged wholly to God, and he had the right to do whatever he wanted with me. I was, as the Apostle Paul said, God’s slave.

Add to these beliefs my conviction that the Bible is the very words of God and that I had an intimate relationship with God where I talked to him (in prayer) and he talked back to me (through the Holy Spirit), it is not surprising that my life was in a state of constant turmoil. Peace? How could I have peace when there were sins to be confessed and eradicated. Remember, Evangelicals believe that all of us of daily sin in thought, word, and deed. Unlike Catholics who seemly to only sweat the big stuff, Evangelicals believe any thought, word, or behavior that does not conform to teachings of the Bible (and the leadership of the Holy Spirit) is a sin. Jesus, himself, taught this when he said in Matthew 5:28, But I say unto you, That whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart.

Imagine how difficult life was for me when virtually everything I did in life was potentially a sin. Worse yet, I had to judge my motives for doing anything. Giving $50 to a homeless person was considered an act of compassion, but if I gave the money so people would think well of me, I had sinned against God. And then there were sins of commission and omission. Not only could thoughts, words, and deeds be sins, but failing to do something could be a sin too. Murdering someone was certainly was a sin, but so was not trying to stop abortion doctors from murdering zygotes (Greek for babies).

What I have written above about my spiritual quest can be summed up this way: I had a thirst for God. I needed God more than anything. I wanted his presence and power in my life. I read Christian biographies of great men who were devotes seekers God, men such as Hudson Taylor, E.M. Bounds, C.T. Studd, John Wesley, David Brainerd, D.L. Moody, Charles Spurgeon, Adoniram Judson, George Whitfield, George Muller, Nate Saint, and Jim Elliot. These stories stirred a yearning in me that, for many years, could not be quenched.

Of course, living this way is impossible, despite what preachers might tell you. Trust me, there’s not a preacher on earth, dead or living, who met the mark. But Bruce, what about the Christian biographies that suggest otherwise. Like all biographies, Christian ones are an admixture of truth and fiction. Unfortunately, Evangelicals only want to hear stories about winners; stories about people who were victorious; stories about people they could aspire to be. The recent death of Billy Graham has brought out all sorts of fantastical stories about the barely human Graham. Much like the Beatles decades ago, Graham has been made out to be bigger than Jesus. For those of us who don’t buy the Graham myth, we know the rest of the story. All we need to do is look at his two children, Franklin Graham and Anne Graham Lotz. Both of them are hateful, mean-spirited, caustic Fundamentalists. Where did their beliefs come from? The notion that Billy was not a Fundamentalist is laughable.

It took me until I was in my 40s before I realized that striving for holiness and perfection was a fool’s errand; that no matter how much I devoted myself to God and the ministry, my life was never going to measure up. Decades of denying self had destroyed my self-worth. Jesus was preeminent in my life, but Bruce was nowhere to be found (and my wife, Polly, could tell a similar story). I spent a decade trying to be a “normal’ Christian, but I still battled with thoughts about not doing enough for the cause of Christ; not doing enough to win souls; not doing enough to advance God’s kingdom to the ends of the earth. By the time I left the ministry in 2005, a lifetime of thirsting for God had led to dehydration and almost killed me. I have no doubt that my commitment to serving God day and night; to burning the candle at both ends; to working while it is yet day, for night is coming when no man can work, played a part in my declining health. And, at some level, I knew this, but I told myself, it’s better to burn out than rust out.

Come November, it will be ten years since I walked away from Christianity; ten years since Jesus and I divorced; ten years since I realized that the Bible was not what Christians claim it is; ten years since I concluded that the Christian narrative was false. Once the Bible was no longer central in my life, I was forced to build, from the ground up, a new moral and ethical framework. This, of course, required me to abandon or set aside the countless beliefs, commands, and laws that had governed my life for fifty years. Most of all, I had to find the life that had been swallowed up by God, the Bible, and the ministry. Somewhere along the way, Bruce Gerencser died, and I had to find where and start over. I had to answer two crucial questions: who are you and what are you? For a few years, this process was quite painful, and without regular counseling sessions with a secular psychologist, I doubt that I would have been able to undergo it. Not that I have, in any way, arrived. I am still reconnecting with who I really am. I am still learning about my emotions; emotions that I had, at one time, surrendered to Jesus by laying them at the foot of his cross.

Rebooting your life at age fifty isn’t easy, as anyone who has done so will tell you. This is why most people who leave Christianity do so at much younger ages. By the time one reaches one’s fifties, it is hard to abandon a lifetime of beliefs, practices, and experiences. On one hand, I felt, and continue to feel, a great sense of freedom. I am now free from the bondage of religion. Much like the Israelites and their flight from the bondage of Egypt to the Promised Land, my Promised Land journey has been fraught with uncertainty and doubt. I wish I had come to the light decades before, but crying over what might what have been accomplishes nothing. I live in the here and now. My present life is all I have, and once it is gone, that’s it. No heaven, no hell, no afterlife. This is why I encourage people who leave Christianity to focus on the here and now. Evangelicals are fond of saying, only one life, twill soon be past, only what’s done for Christ will last. For the atheist, this little ditty goes this way: only one life, twill soon be past, and once it’s past you’re dead, so you best get to living.

In 2008, I was psychologically dehydrated, near death. It was only when I realized I was doing this to myself that I began to find strength and healing. I remain a work in progress. I will never arrive, but as the old gospel song says, I’ve come too far to turn back now. This blog will remain one man telling his story; a running biography of my former life as a Christian and my present journey as an atheist and a humanist. I have a story to tell, a story of death and resurrection. Thank you for continuing to walk along with me.

What follows is a letter I wrote several days ago to the athletic director at

What follows is a letter I wrote several days ago to the athletic director at

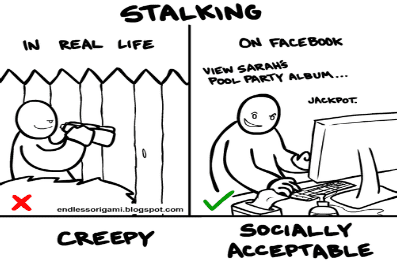

My wife, Polly, had a conversation the other day with someone at work which unnerved her a bit. The person Polly was talking to let it be known that she had done a Google search on Polly’s name and found out that her husband had a blog. Polly is not too tech savvy when it comes to the Internet. She’s satisfied to use it get information, read her email, read books, and access social media. She’s never cyberstalked anyone. I explained to her that cyberstalking is quite common; a practice that I engage in on occasion. ’Tis the nature of the Internet. I see in this blog’s logs numerous searches related to my name every day. I used to obsess about this, wondering, who is trying to find information about me? I now know, as a public figure, that whatever I say on this blog, on other sites, and on social media, can and will be read by others. As a writer, I know that there is no such thing as secrecy on the Internet. I must live with the fact that anyone can read what I have written, and they can then use and misuse my writing. New bloggers are often surprised when they find out that other people, people they don’t know, can read their writing. That’s the nature of the Internet. It is best to assume that anything you say and do on the Internet is akin to you standing stark naked before the world.

My wife, Polly, had a conversation the other day with someone at work which unnerved her a bit. The person Polly was talking to let it be known that she had done a Google search on Polly’s name and found out that her husband had a blog. Polly is not too tech savvy when it comes to the Internet. She’s satisfied to use it get information, read her email, read books, and access social media. She’s never cyberstalked anyone. I explained to her that cyberstalking is quite common; a practice that I engage in on occasion. ’Tis the nature of the Internet. I see in this blog’s logs numerous searches related to my name every day. I used to obsess about this, wondering, who is trying to find information about me? I now know, as a public figure, that whatever I say on this blog, on other sites, and on social media, can and will be read by others. As a writer, I know that there is no such thing as secrecy on the Internet. I must live with the fact that anyone can read what I have written, and they can then use and misuse my writing. New bloggers are often surprised when they find out that other people, people they don’t know, can read their writing. That’s the nature of the Internet. It is best to assume that anything you say and do on the Internet is akin to you standing stark naked before the world.