The call came from California. A woman told Coral Springs Police she had recently learned something terrible: A South Florida man had molested her daughter for years. It began when the girl was just 4 years old.

An officer noted the information and called the victim, who was then a teenager. She confirmed the story in stomach-churning detail.

The man had forced her to perform oral sex, she said. He would regularly “finger and fondle her” genitals, make her touch his penis, and “dirty talk” to her. The abuse lasted until she was a teenager, she told the cop. She’d never even told her family about the crimes.

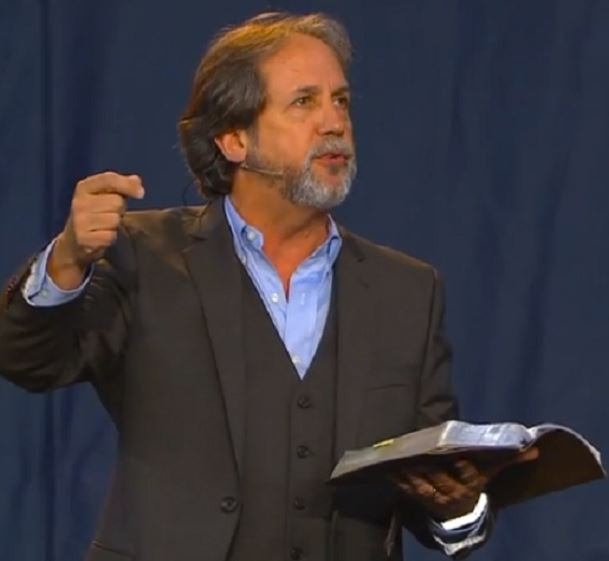

By the end of that harrowing call on August 20, 2015, police knew the accused predator was no ordinary suspect. His name was Bob Coy, and until the previous year, he’d been the most famous Evangelical pastor in Florida.

Over two decades, Coy had built a small storefront church into Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale, a 25,000-member powerhouse that packed Dolphin Stadium for Easter services while Coy hosted everyone from George W. Bush to Benjamin Netanyahu. With a sitcom dad’s wholesome looks, a standup comedian’s snappy timing, and an unlikely redemption tale of ditching a career managing Vegas strip clubs to find Jesus, Coy had become a Christian TV and radio superstar.

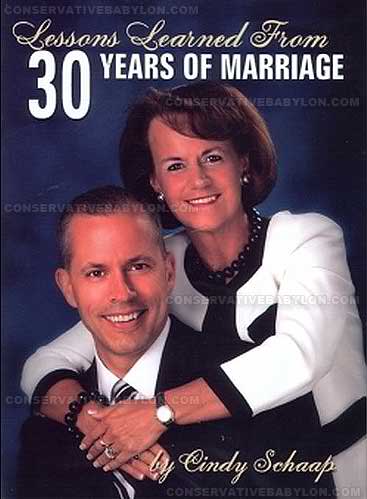

But then, in April 2014, he resigned in disgrace after admitting to multiple affairs and a pornography addiction. Coy shocked his flock and made national headlines by walking away from his ministry, selling his house, and divorcing his wife.

The sexual assault claims, which have never before been divulged, raise new questions about the pastor, his church, and the police who handled the case. Documents show that Coral Springs cops sat on the accusations for months before dropping the inquiry without even interviewing Coy. His attorneys, meanwhile, persuaded a judge with deep Republican ties to seal the ex-pastor’s divorce file to protect Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale from scrutiny.

The revelations come at a sensitive moment for Calvary’s national network of about 1,800 churches, which have been riven by legal infighting and dogged by claims that bad pastors have been allowed to run amok. In fact, at least eight pastors, staff members and volunteers in Calvary Chapel’s network around the United States have been charged with abusing children since 2010. In one case, victims claimed the church knowingly moved a pedophile to another city without warning parents.

“Religious leaders have a tremendous amount of power over their flock,” says Scott Thumma, a professor of sociology of religion at Hartford Seminary who has studied the Calvary movement. “If Calvary gives these pastors this much authority and they use and abuse it with no accountability, they have to blame themselves.”

Coy, who was never charged with a crime, lay low after leaving Cavalry but recently turned up at Boca Raton’s Funky Biscuit, where he helps manage the club. Tracked down at the bar on a recent weeknight, the well-dressed ex-pastor looks no different from the days when he preached to thousands of followers. He declined to discuss the child abuse case except to say he is innocent and passed a polygraph test to prove it.

“I can’t discuss it on the record,” he said, before adding cryptically: “If you’re foolish enough to go through with this story… it would hurt a lot of people.”

Were there other abuse claims against Coy during the nearly three decades he controlled Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale? The church won’t say, though a spokesman says the chapel was “saddened to hear of the allegations.” That’s not good enough, critics say.

“There could be other victims out there,” says Michael Newnham, an Oregon-based pastor who runs a blog critical of Calvary Chapel. “We need answers.”

….

On a Sunday evening in April 2014, thousands packed into Calvary Chapel’s sanctuary, a cavernous space that looks more like a midsize city’s convention center than a church. As they sank into plush, arena-style seats and flipped open well-thumbed Bibles, Coy’s followers quickly noticed something was very wrong. The rock band that usually played raucous hymns to start services was missing. And a grim-looking assistant pastor, gripping a letter, was walking across the stage.

Pastor Bob had suddenly resigned, the assistant pastor told the stunned crowd. He had admitted to a grave “moral failing.” Ushers passed tissue boxes down the rows as his followers wept.

“People were really, really hurt,” says Colleen Healy, a Broward resident who began following Coy in 1995. “I was really hurt. I’ll never forget that meeting.”

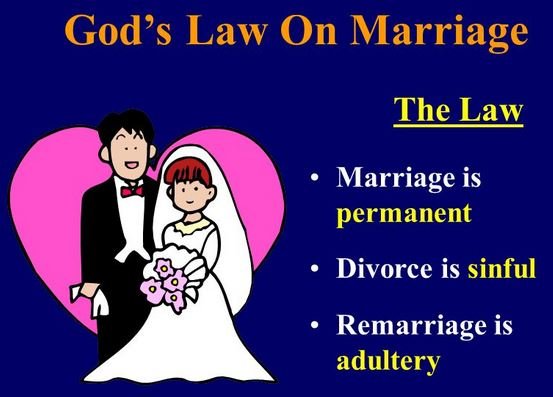

Coy’s preaching career ended with shocking speed, but his sex scandal was far from the first for Calvary Chapel. In fact, the church had been battling accusations nationwide for years that it empowered predatory pastors while demanding little accountability.

The root of Calvary’s problems, critics say, lies in its unique structure. Unlike many Protestant churches, which set up powerful boards of elders to oversee ministers, Calvary used a management style Smith called the “Moses method.”

“Moses was the leader appointed by God,” Smith told Christianity Today in 2007. “We are not led by a board of elders.”

Instead, the pastors Smith installed in his hundreds of megachurches, which are similar to Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale, had nearly unlimited power over budgets, personnel, and message. And even if complaints arose, Smith’s answer was often to give wayward preachers second and third chances.

In 2007, Christianity Today spoke to numerous Calvary pastors across the country. Some complained anonymously that Smith was “dangerously lax in maintaining standards for sexual morality” among his preachers. “Those men cannot call sin sin,” one 20-year veteran of the church complained to the publication.

There were ample cases to make that point. In 2003, John Flores, a pastor at Smith’s flagship in Costa Mesa, was arrested for having sex with the 15-year-old daughter of another pastor. According to Christianity Today, he’d been fired twice before for sexual misconduct, including once after getting caught having sex on church grounds, but kept getting his job back. (Flores was eventually convicted of sex with the minor.)

Two years later, a Calvary Chapel in Laguna Beach fired its pastor for adultery and embezzlement — but Smith quickly rehired him to preach at the nearby Costa Mesa church.

That same year, the church found itself in a bizarre scandal centered on a lucrative, 400-station radio network and its head, Idaho-based Pastor Mike Kestler. He had been in hot water in the ’90s when multiple women in his church claimed he’d sexually harassed them, but Smith gave him another chance.

In a lawsuit, a woman named Lori Pollitt said after she had moved from Texas to Idaho to work for Kestler, he repeatedly demanded she divorce her husband, give up her children to adoption, and marry him. When she rebuffed him, she said he stalked her and put a “hangman’s noose” in front of her house.

This time, Smith and his son Jeff actually turned on their pastor, pushing him out. They ended up locked in dueling lawsuits, with the pastor accusing Calvary’s leaders of skimming profits and the Smiths charging that he used his influence running the radio stations to pressure women into sex. (The cases were settled out of court.)

The next year, Santa Ana police investigated the Costa Mesa chapel after a 12-year-old told a staffer that a pastor had been touching her inappropriately. Police said they couldn’t find enough evidence to press charges, but the staffer claimed the church forced him to resign for alerting the authorities.

In 2006, Coy’s church in Fort Lauderdale landed in court over claims of lax oversight. A Calvary Chapel member named Rodger Thomas was arrested that year and charged with repeatedly molesting a 15-year-old girl at a high school run by the church. Two years later, her family sued Calvary, alleging leaders should have done more to stop Thomas. A jury awarded the family $360,000 but ruled Calvary wasn’t culpable.

The most serious claim against Calvary’s national church came in 2011, when four men in Idaho filed a federal suit alleging a youth minister named Anthony Iglesias had molested them between 2000 and 2003. Even worse, they said church officials knew full well he was a pedophile: He’d been kicked out of another Calvary youth ministry in California after being charged with sex crimes there.

That case was settled out of court, but the attorney who brought the case says that, in general terms, Smith’s habit of forgiving and rehiring pastors who have committed sexual offenses is a recipe for disaster.

“Typically, how it goes in these cases is you have a violator in the church, but the leaders will have this notion that if he repents, he’s forgiven, and then we don’t have to talk about it any more,” says Leander James, who specializes in church child abuse cases. “That whole approach always ends up hiding pedophiles.”

Neither Calvary Chapel Costa Mesa, the movement’s flagship, nor the Calvary Chapel Association returned messages from New Times seeking comment for this story.

It’s still not clear how Coy’s sexual indiscretions came to light in 2014. But two weeks after his surprise resignation, Assistant Pastor Chet Lowe filled Coy’s followers in on what had happened.

“Our former pastor was caught in sin,” Lowe said April 16, according to the Sun Sentinel. “Our pastor, he committed adultery with more than one woman. Our pastor, he committed sexual immorality, habitually, through pornography. Rest assured, God will not be mocked.”

….

Coy’s faithful didn’t know it, but just over a year after the pastor’s resignation for adultery, Coral Springs Police launched their investigation into a far worse allegation. It’s unclear how seriously they took the claim of the teenager — whom New Times is not naming in accordance with our policy on reporting on victims of sexual abuse — who said Coy had forced her to have sex even when she was only 4 years old. But the case soon stalled.

The department assigned the case to Det. Jeff Payne, a veteran investigator in the usually sleepy, affluent suburb of 120,000. Payne had experience with sensitive cases involving sex crimes; earlier that year, he’d investigated a high-ranking cop for allegedly assaulting a 13-year-old girl. Payne had taken his case against Fort Lauderdale Police Maj. Eric Brogna to the Broward County State Attorney’s Office, but prosecutors declined to press charges.

In the Coy case, though, Payne never made that kind of headway. Shortly after resigning, the disgraced pastor moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee, where Calvary Chapel has another affiliate church. (It’s unclear if he worked there.) Coy says he was never approached by the police about the allegations.

Indeed, police records show no progress on the case until eight months later, on April 4, 2016, when Coy’s young accuser showed up at Coral Springs Police headquarters. She told Payne she was “moving tomorrow [overseas] on a mission trip with the church, and asked if it was possible to destroy any record of [her] abuse,” the detective wrote in a closeout memo. The woman told him “she had an experience with God and has found forgiveness” for Coy over his abuse.

….

Coy has never been criminally charged, and if there were other cases of sexual harassment or abuse in the decades he ran Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale, neither the church nor cops have revealed them. The church didn’t respond to a detailed set of questions from New Times, instead sending a general statement about the former pastor.

….

This year, Calvary has been hit by even more sexual abuse claims. In May, Matt Tague, an assistant pastor at North Coast Calvary Chapel in San Diego, was arrested on 16 counts of lewd and lascivious acts on a minor under 14 years old. Police say the victim wasn’t a church member, and Calvary Chapel says it immediately fired Tague upon learning about the claims.

Then, on July 18, police arrested 41-year-old Roshad Thomas, who had spent 13 years as a volunteer youth pastor at Calvary Chapel Tallahassee. He’s accused of molesting at least ten children aged 13 to 16 over several years, victimizing members of the youth group he led after taking them back to his apartment.

Police say Thomas has admitted to the abuse (though his criminal trial is pending). The chapel’s founder, Kent Nottingham, told a local TV station that there’d been no suspicion of abuse and that he was “shocked.”

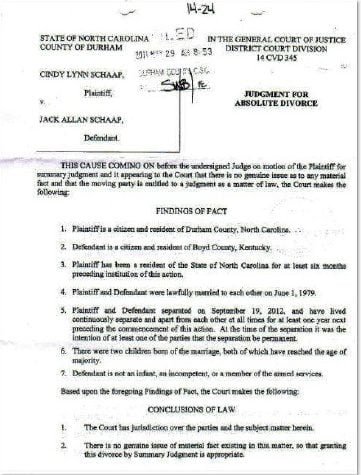

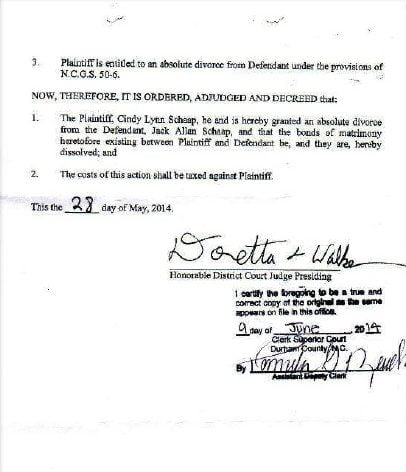

Coy has also been dragged through legal battlefields since his resignation from the church. In January 2016, he and Diane filed for divorce in Broward County. They’d already sold their Coral Springs house about six months after he resigned; the settlement divided their substantial remaining assets — including a $330,000 Hillsboro Beach condo he still owns — and defined custody of their two children. The divorce file includes nearly 30 pages of documents related to their finances and settlements.

But on February 22 of that year, the case went to Judge Tim Bailey, a member of a powerful conservative family; his father, Patrick, founded the Pompano Beach Republican Club, and both father and son had chaired Broward’s Judicial Nominating Commission. That body recommends candidates for higher legal office to the governor. In Coy’s case, Bailey made a relatively unusual ruling: All financial documents would be kept secret. Why? To “avoid substantial injury” to Coy’s former employer — Calvary Chapel — according to the court file.

To critics such as Newnham, there’s only one reason to fight for a ruling like that: to hide from churchgoers the amount of cash the church gave Coy to go away. The case reeks of political favoritism. “These guys have been covering for Coy for a long time,” Newnham says, “and they’re still covering for him now.” (Judge Bailey didn’t respond to messages from New Times to comment on this story.)

That’s right, Bob Coy is trying to get back in the “game.” And I have no doubt that he will find people who are willing to play along with him. Much like King David — a man after God’s own heart — who committed adultery with Bathsheba and had her husband murdered, Coy will surely convince people that his “sins” are under the blood — forgiven and forgotten.