It’s the most common question religious folks pose to atheists: “Where do you get your morals?”

Whether at a dinner party or class reunion, a PTA meeting or a pig pickin’, whenever God-fearing people find out that we don’t believe in the Lord, don’t believe in an afterlife, don’t attend church, synagogue, mosque, or temple, don’t follow a guru, don’t obsess over ancient scriptures, and don’t care much for preachers or pontiffs, they immediately inquire about the possible source of our morality — which they find hard to fathom.

And the question “Where do you get you morals?” is usually asked with an embedded implication that morality obviously comes from God and religion, so if you don’t have either, then you must have no source for morality. On top of this problematic implication, there is often an accompanying judgmental, sneering tone; it’s as if what they really want to say is “You must be an immoral lout if you aren’t religious and don’t believe in God.”

To be fair, not everyone who asks atheists where they get their morals is implying something unkind. Given that religion has so fervently, forcefully insisted that it is the only source of morality for so many centuries, many people just honestly and naively believe that to be the case. Thus, not having thought too much about it, they are genuinely curious about where a person gets his or her morals, if not from religion.

But even if the question is asked in total unprejudiced earnestness, it is still a rather odd query. After all, “Where do you get your morals?” suggests that morals are things that people go out and find in order to possess. Like shoes. Or a new set of jumper cables. It implies that people are living their lives, doing this and that, and then at some point, they decide to drive downtown or go online and get ahold of some morals — as if ethical tenets and moral principles were consciously adopted in some sort of deliberate process of acquisition.

Morality, however, doesn’t really work that way. While people may deliberately choose to get their donuts from a certain shop or decide to get their dog from a certain pound, when it comes to the core components of our morality — our deep-seated proclivities, predilections, sentiments, values, virtues, and gut feelings in relation to being kind and sympathetic — these things are essentially within us. They are an embedded, inherited part of us. We don’t go out and “choose” them, per se. Sure, we may change our minds about a certain social issue after learning more about it and critically reflecting upon it; we may develop a love or distaste for something after having had certain new experiences in relation to it; we may start to live our lives differently, with different ethical priorities, after we marry a certain person and cohabitate with them for an extended period of time; we may find our political positions shift when we move to a new state or country and live there for a while.

However, when it comes to our underlying morality, it is not generally something that we “get” in a conscious, deliberate, choosing way. Rather, our deep-seated sense of how to treat other people, our capacity for empathy and compassion, our desire for fairness and justice — these are things that we naturally manifest: our morals have been inherited from our evolutionary past, molded through our early childhood nurturance, enhanced and channeled through cultural socialization, and as such — to paraphrase sociologist Émile Durkheim — they “rule us from within.”

What exactly is it that rules us so — morally speaking? And what are the specific foundational sources of our moral proclivities and ethical tendencies? There are four: 1) our long history as social primates, evolving within a group context of necessary cooperation; 2) our earliest experiences as infants and toddlers being cared for by a mother, father, or other immediate caregivers; 3) unavoidable socialization as growing children and teenagers enmeshed within a culture; and 4) ongoing personal experience, increased knowledge, and reasoned, thoughtful reflection.

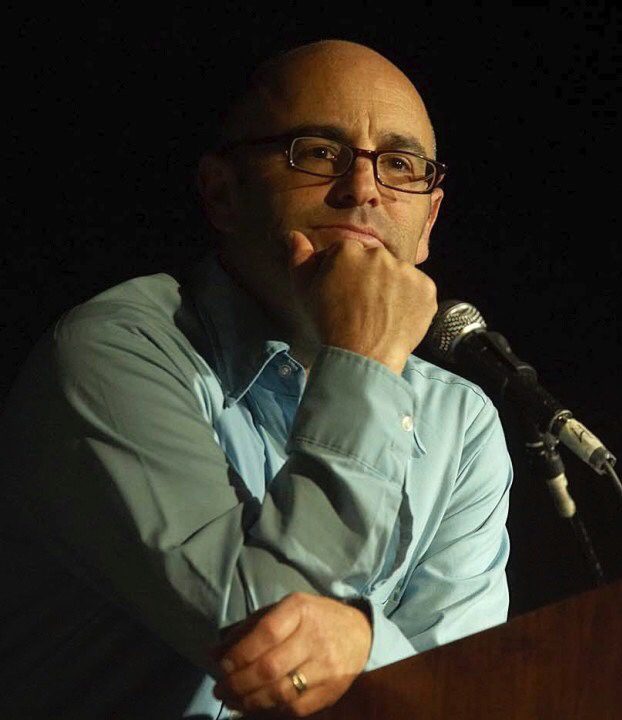

— Phil Zuckerman, What It Means to Be Moral: Why Religion Is Not Necessary for Living an Ethical Life

Purchase What It Means to Be Moral: Why Religion Is Not Necessary for Living an Ethical Life

I think the fundamental problem with the religious approach to morality is that of why we ‘interact’ with it. If morality is put inside us as part of our nature (it is, of course, but that’s via evolution, and behavioural nurture, not god) then we still have to interpret it. Hence ‘thou shalt not kill’ can be negated in many ways, such as self defence, war, or capital punishment. It also doesn’t explain why so many people choose to defy it. If it’s more a question of it being in a book that we know as the ‘bible’, well that doesn’t work either. People who’ve never heard of the bible still know how to behave socially but, more to the point, even if the bible does contain some level of sensible moral constraints then so what? One must still assess the constraint against one’s own sense of right and wrong, which is why so much biblical so-called morality we reject. Whichever route we take we find the same: morality is subjective, based partly on personal feelings of fairness and empathy, and partly on how society sees things.

It’s interesting how across cultures “don’t take things that don’t belong to you” is a universal construct. He is right, people assume that religions own the market on morals, but that’s a harder argument to uphold when you see evangelical Christians promoting putting little kids in cages, treating LBGTQ people like they are dung, and promoting racist policies.

This is purely anecdotal, but I feel like I have become a kinder, nicer person after leaving evangelicalism and its rules and regulations about things like who one is supposed to live, what music one is supposed to listen to, whether one should be unequally yoked to someone outside the tribe.

this question is always asked when one says they no longer believe or are doubting. but I find that the further away I am from my childhood indoctrination, the nicer and gentler I have become. I am not as apt to judge harshly and demand things from others. on the other hand, the deeper my parents go into religion, they have become nearly unbearable and my grown kids will hardly have anything to do w/them. we left religion/church when our kids were still fairly young, so they do not believe they must tolerate their grandparents’ bad behavior. we are more liberal Christians at this point but seem to be on the way out day by day. religious folks complain about how things are getting worse, but I disagree. people minding their own business and being more kind is a good thing in my opinion. it seems to be religious people carrying out acts of terror against others or stealing, cheating, etc. the sooner we break the power of religion in the public sphere, the better off the world will be.

Maybe so, but I challenge anyone to find, “Love your enemies” in evolutionary development.

My morals came from Jesus’s teachings, as imparted to me by my religious grandmother. I don’t need to accept the supernatural elements of religion to recognize the ethics that Jesus, Buddha, and maybe others taught, transcending anything innate to primates.

Brunetto, I challenge you to meditate some more on what the words mean at their essence. Doing good to those who hate you is very evolutionary even among my honey bees who will not waste too much time fighting with wasps while in the presence of a sweet nectar meal offered them by nature. They will tussle and fight some under pressure but they coexist when possible. Love your enemies is primarily about self-survival and before you defend your position let me agree with your position. Your understanding of Love your enemies comes from Jesus as taught to you by grandmother.

Mine goes way beyond my religious grandmother (who wasn’t a very nice person to me. I wrote a poem about her called, Grandmother Turnip. You get the drift.)

When I attended the American Atheists convention in Memphis several years ago, Ayaan Hirsi Ali spoke about the differences in religions, contrasting Christianity and Islam. Her point was that Christianity is better.

And that seems to me a better approach than looking to evolution to explain ethics. I would just say I’m very particular about what I take from religions. The Sermon on the Mount, but not the dogma of Paul. The writings of John, but not the Levitical law. The benefits of meditation without the superstition of karma and nirvana. The Golden Rule, over all.

Maybe it’s just my sometimes anxious personality, but I just feel better when I know I’m doing the right thing, treating people with kindness, and all of the things we associate with morality. I feel a sense of well-being and calm. I really don’t need the promise of a glorious if unrealistic heavenly reward for being a decent person. It just feels good in the moment. If the religious among us don’t understand that they’re in bigger trouble than they realize.

I got my morals they way every other human did. We are mammals and social animals (we have somewhat of a herd instinct). We bear children that take quite some time to become independent. All mammals are born weak. Even those who are up and running within just a few hours of being born. They are still weak and small and the target of predators, so parents have to protect them. This care of the young extends to both the females and males of the species. This “care” is the focus of our morality. We extend that caring to close relatives and, over time, and socializing, it has been extended father and farther.

This is the basis of all human morality. If we do not protect our young, we fail as a species. If the stronger males do not protect the smaller females we do not succeed as a species. There are a number of ways to do this, of course, elephant females band together to for a formidable group. The males are told off. This si one pattern. Another is for the males and females of a small family to stick together. This is another. As the families grow and grow, they would spit and form non competing groups. Family relationships between groups would help extend “caring” from group to group. And so on.

Only ambitious religious elites claim that the morality that existed for many, many generations before their religion was created comes from their god. By making it a “gift” from their god, the religious elites create a sense of obligation in their god’s followers to repay that gift, to not waste that gift. These and other forms of social control have been used to establish political power … for the elites.

I’ve noticed that a billion people in China seem to have very similar values to what the bigoted trash refers to as “Judeo-Christian” values and is really “Judeo-Christo-Islamic values.” All without believing that there’s an invisible man in the sky with a list of rules that you must follow or he’ll cast you in a pit of fire to suffer in agony for all eternity.

The real core of “Judeo-Christo-Islamic” values is fear. The punitive personality.