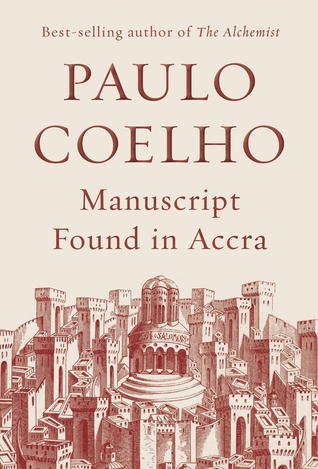

Manuscript Found in Accra is written by Brazilian author Paulo Coelho. The book was translated from Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa and is published by Alfred A Knopf.

The publisher graciously provided me a copy of the book to review. Manuscript Found in Accra is 190 pages long and can be read in several leisurely sittings.

This is the first Paulo Coelho book I have read. Quite frankly, until the publisher representative contacted me, I had never heard of Paulo Coelho. This is my loss, since millions of other people know who Paulo Coelho is. According to back flap of the book, Coelho has written numerous books; books such as The Alchemist, Aleph, Eleven Minutes, and The Pilgrimage. His books have been translated into 74 languages and over 140 million books have been sold.

Manuscript Found in Accra is best described as wisdom literature. Drawing on the collective wisdom of the world’s religions, Coelho tells a masterful story that forces readers to contemplate and consider their own lives, and the meaning, purpose, and direction thereof.

While the book is littered with religious and spiritual references, it is not strictly a religious book. Coelho takes readers beyond the boundaries that sectarian religions erect and encourages them to see the wisdom found not only in religious texts but also in the collective experiences that humanity shares.

The main character of Manuscript Found in Accra is the Copt. The book focuses on the Copt’s interaction with the people of Jerusalem on July 14, 1099.

Roman Catholic Crusaders have surrounded Jerusalem. Attack is imminent. Many of the residents of Jerusalem will flee before the battle, yet others will stay to fight, knowing that they will likely die. Before this historic battle takes place, the Copt asks all the people to come to the city square. He asks the leaders of the three Abrahamic religions to join him there.

The Copt is described as:

…a strange man. as an adolescent, he decided to leave his native city of Athens to go in search of money and adventure. He ended up knocking on the doors of our city, close to starvation. When he was well received, he gradually abandoned the idea of continuing his journey and resolved to stay.

He managed to find work in a shoemaker’s shop, and—just like Ibn al-Athir—he started recording everything he saw and heard for posterity. He did not seek to join any particular religion, and no one tried to persuade him otherwise. As far as he is concerned, we are not in the years 1099 or 4859, much less at the end of 492. The Copt believes only in the present moment and what he calls Moira—the unknown God, the Divine Energy, responsible for a single law, which, if ever broken, will bring along the end of the world.

The people, along with their religious leaders, gather in the city square, the very same city square where Jesus was condemned to die. The Copt says to the people:

From tomorrow, harmony will become discord. Joy will be replaced by grief. Peace will give way to a war that will last into an unimaginably distant future…

They can destroy the city, but they cannot destroy everything the city has taught us, which is why it is vital that this knowledge does not suffer the same fate as our walls, houses, and streets. But what is knowledge?…

It isn’t the absolute truth about life and death, but the things that help us to live and confront the challenges of day-to-day life. It isn’t what we learn from books, which serves only to fuel futile arguments about what happened or will happen; it is the knowledge that lives in the hearts of men and women of good will…

I am a learned man, and yet, despite having spent all these years restoring antiquities, classifying objects, recording dates, and discussing politics, I still don’t know quite what to say to you. But I will ask the Divine Energy to purify my heart. You will ask me questions, and I will answer them. This is what the teachers of ancient Greece did; their disciples would ask them questions about problems they had not yet considered, and the teachers would answer them.

Someone in the crowd asks, what shall we do with your answers?

The Copt replies:

Some will write down what I say. Others will remember my words. The important thing is that tonight you will set off for the four corners of the world, telling others what you have heard. That way, the soul of Jerusalem will be preserved. And one day, we will be able to rebuild Jerusalem, not just as a city, but as a center of knowledge and a place where peace will once again reign.

A man in the crowd says, we all know what waits us tomorrow. Wouldn’t it be better to discuss how to negotiate for peace or prepare ourselves for battle?

The Copt turns and looks at the religious leaders to see if they have anything to say, then he turns back to the crowd and says:

None of us can know what tomorrow will hold, because each day has its good and its bad moments. So, when you ask your questions, forget about the troops outside and the fear inside. Our task is not to leave a record of what happened on this date for those who will inherit the Earth; history will take care of that. Therefore, we will speak about our daily lives, about the difficulties we have had to face. That is all the future will be interested in, because I do not believe very much will change in the next thousand years.

The people proceed to ask the Copt twenty questions. Each chapter in the book details the Copt’s answer to their questions. The questions and answers deal with matters close to the heart of all of us: love, fear, loss, death, beauty, courage, friendship, and dreams. Regardless of one’s religious persuasion, Manuscript Found in Accra is a treasure-trove of wisdom. It is a book that can be read over and over, with each reading giving new insight.

My favorite chapter is one where a person preparing to die in battle the next day asks:

We were divided when what we wanted was unity. The cities that lay in path of the invaders suffered the consequences of a war they did not choose. What should the survivors tell their children?

The Copt replies:

…do not seek to be loved at any price, because Love has no price.

Your friends are not the kind to attract everyone’s gaze, who dazzle and say: “There is no one better, more generous, or more virtuous in the whole of Jerusalem.”

Your friends are the sort who do not wait for things to happen in order to decide which attitude to take; they decide on the spur of the moment, even though they know it could be risky.

They are free spirits who can change direction whenever life requires them to. They explore new paths, recount their adventures, and thus enrich both city and village.

If they once took a wrong and dangerous path, they will never come to you and say: “Don’t ever do that.”

They will merely say: “I once took a wrong and dangerous path.”

This is because they respect your freedom, just as you respect theirs.

Avoid at all costs those who are only by your side in moments of sadness to offer consoling words. What they’re actually saying to themselves is: “I am stronger. I am wiser. I would not have taken that step.”

Stay close to those who are by your side in happy times, because they do not harbor jealousy or envy in their hearts, only joy to see you happy.

Avoid those who believe they are stronger than you, because they are actually concealing their own fragility.

Stay close to those who are not afraid to be vulnerable, because they have confidence in themselves and know that, at some point in our lives, we all stumble; they do not interpret this as a sign of weakness, but of humanity.

Avoid those who talk a great deal before acting, those who will never take a step without being quite sure that it will bring them respect.

Stay close to those who, when you made a mistake, never said: “I would have done it differently.” They did not make that particular mistake and so are in no position to judge.

Avoid those who seek friends in order to maintain a certain social status or to open doors they would not otherwise be able to approach.

Stay close to those who are interested in opening only one important door: the door to your heart. They will never invade your soul without your consent or shoot a deadly arrow through that open door.

Friendship is like a river; it flows around rocks, adapts itself to valleys and mountains, occasionally turns into a pool until the hollow in the ground is full and it can continue on its way.

Just as the river never forgets that it’s goal is the sea, so friendship never forgets that its only reason for existing is to love other people…

I heartily recommend Manuscript Found in Accra. I am an atheist, and I know that some of you might find my recommendation of Paulo Coelho’s book strange. Yet I found the book affirming many of the humanistic values I hold dear. Yes, Coelho is a religious man, a practicing Catholic, but can we not all learn from people who are different from us, people who, despite our differences, hold a common humanity with us?

This is the first spiritually oriented book I have read since leaving Christianity almost 5 years ago. For a time, the wisdom-well was poisoned and I could not read books with any religious or spiritual sympathies. But now I find myself yearning for books that speak to my humanity, books that call on me to reflect on who and what I am and how I want to live my life.

The strict materialist will find little to like in Manuscript Found in Accra. But for those who dream of a better tomorrow, who still have hope and seek a world of peace, Paulo Coelho’s latest book will inspire and provoke us to be better human beings.

You can buy Manuscript Found in Accra here.

Note:

TLC Book Tours handles some of the book reviews I have done. If you have a book that you would like to publicize please contact them. I have found the staff at TLC Book Tours a delight to work with.

Share This Post On Social Media: