Guest Post by ObstacleChick

Guest Post by ObstacleChick

Recently, I was back in the Bible Belt where I grew up, as I dropped my daughter off for her first year of college in Nashville. I was raised in a Southern Baptist church and attended a Fundamentalist Christian school, but I started moving away from those doctrines at age eighteen when my church started teaching complementarianism (then called Biblical manhood and womanhood). Going to a secular university opened up other ideas to me to which I had not been exposed, and I was able to move away physically and literally from Christian Fundamentalism. My husband was raised nominally Catholic, and we attended progressive Christian church for a while before we both shifted into agnostic atheism. Our children have not been raised with any religious indoctrination, and when my daughter indicated that she wanted to attend university in the South, I thought it would be important to let her know what Evangelical Christians believe so that she wouldn’t be shocked when she found out that some of our family members still believe this way and that some people she encounters in Tennessee may hold these views.

My parents divorced when I was little, and my mom remarried and had another child. My brother is twelve years younger than I am, and his upbringing was quite different from mine. I lived with my grandparents — he lived with his mom and dad. I was sent to private Christian school — he attended public school after he was expelled from the private Christian school in third grade (yes, expelled in third grade; he mouthed off to the teacher and to the principal). My mom and stepdad moved to a different town after I graduated from college, and they left the Southern Baptist Church, eventually ending up at an Independent Fundamentalist Baptist (IFB) church. My brother and his wife and two sons do not attend church. Instead, my brother is part of a Skype men’s prayer and Bible study group, and he reads a lot of Christian books and watches live stream and YouTube sermons. Every night before bed, he teaches and prays with his sons, and he spends time on his own praying before bed. He also posts a lot of Bible verses and links to very conservative Christian articles and YouTube videos on social media; with that evidence, I am confident that he still believes many aspects of Fundamentalist Christianity. I am not sure what my sister-in-law believes, but I don’t get the impression she is as devout as my brother. My brother knows that we are not Bible literalists at all, and he knows that we expose our kids to a lot more of “the world” than he does, but I have not used the “A” word around him yet. He probably thinks we are apostates but still somehow under the umbrella of God. I think he doesn’t ask specifics because he doesn’t want to know, and I don’t bring it up because I don’t want him to excommunicate me from the family.

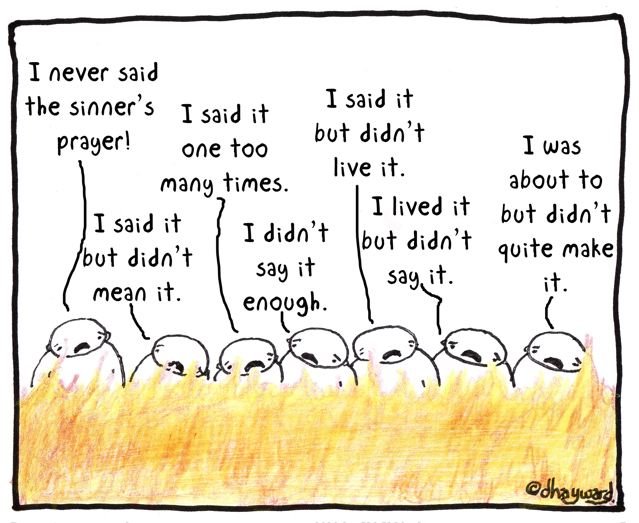

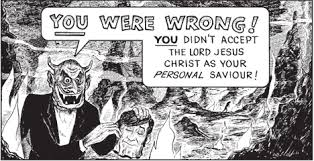

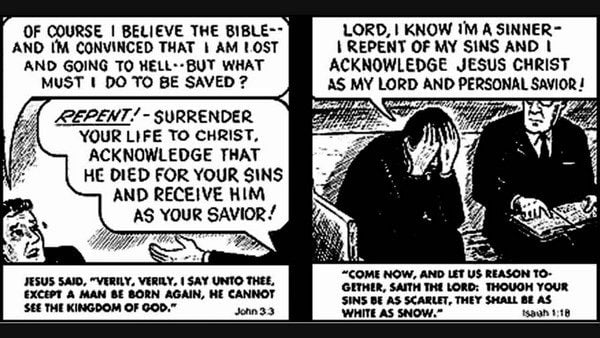

On our long drive from Tennessee back to New Jersey, my husband asked me if my brother believes that we are going to Hell. I told my husband that I am not sure what my brother knows or believes about our religiosity, but it’s certainly a possibility that he might think one or more of us is bound for Hell. According to the doctrines in which we were brought up, I am of the “once saved always saved” crowd, so he probably believes that I am apostate but not necessarily bound for the Lake of Fire. I’m not sure if my brother knows that my husband was Catholic, but he may believe that somehow through my influence my husband is “saved” and that I probably made sure the children “got saved” too. My brother made sure his children said the “Sinner’s Prayer” and he baptized the boys in the bathtub (because somehow that’s allowed, I guess). My husband asked what the “Sinner’s Prayer” is, and I told him it’s some version of admitting that one is a sinner, that one repents of his or her sin, accepts that Jesus is the virgin-born son of God who died for our sins, was buried, resurrected, and ascended to heaven. One must accept that humans are all bound for Hell unless they have accepted the saving grace of Jesus. My husband naively stated, “Oh, it’s like the Creed we stated at church every Sunday.” I said, “Ummmm…sort of — it’s more of a one-and-done statement that you really, really, really have to mean for it to take. And then you get baptized. If it all takes, then you’re ‘saved’ from Hell.”

My husband stated that if my brother and his wife thought there was a possibility that we were bound for Hell, he is hurt and offended that they have not once tried to proselytize to him to make sure. Honestly, I was surprised by his statement, but I can understand why he would feel that way. If you truly believe that someone you care about is in danger of spending eternity in the Lake of Fire – or even if you are an annihilationist and believe that anyone sentenced to Hell immediately ceases to exist — why would you not try to warn that person before it is too late?

I explained to my husband that in Evangelical Christianity, there is great emphasis placed on “witnessing” or proselytizing. Remember the “Great Commission” in Matthew 28:19,20:

Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost: Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you: and, lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world.

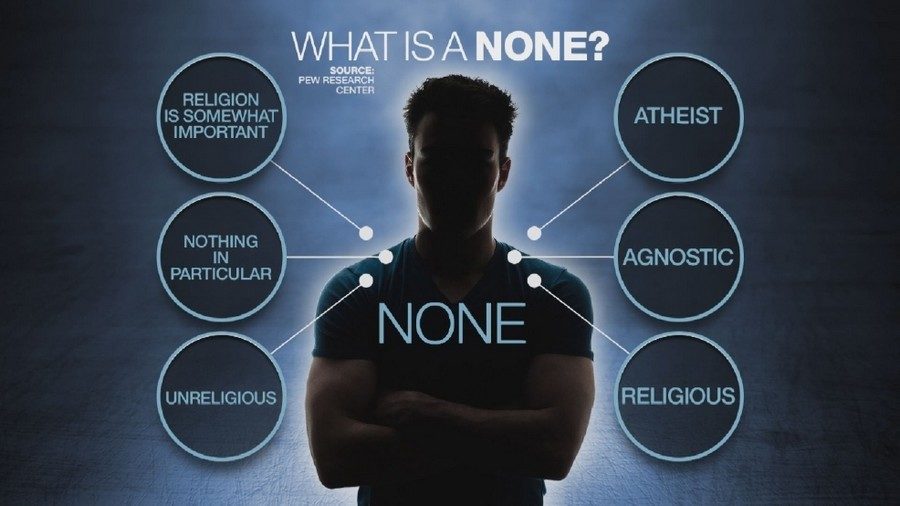

Some Evangelical Christians actively proselytize, verbally witnessing to people they meet or know. Some take a more passive approach, either by wearing Christian-themed clothing, posting Christian-themed signs on their property or vehicles, or decorating their office space with Christian-themed items. Some people make it their life’s vocation, becoming pastors or missionaries. But many (perhaps most?) Evangelicals do not “witness” at all. When I was an Evangelical, I did not actively witness to people. Everyone I knew at school and at church was already “saved.” I worked in a university biochemistry laboratory as a teenager and college student, and I was too intimidated to try to initiate a religious discussion with my coworkers, as all of them had at least a bachelor’s degree, most had doctorates, and I was not as educated as they. Honestly, I felt that Fundamentalist Christianity was a sect for the uneducated, and I assumed my coworkers probably thought so as well.

In any case, I was glad to make it through a trip to Tennessee without people preaching to me about their brand of religion, though I did see my fair share of Christian-themed road signs, T-shirts, and home decor in stores. A lot of people in Tennessee love Jesus!

What are your thoughts on proselytizing? Are you glad when people do not proselytize you, or do you consider that they do not care about you enough to try to witness to you so you escape eternity in Hell or annihilation after death? Did you attempt to proselytize when you were an Evangelical Christian? Why or why not?

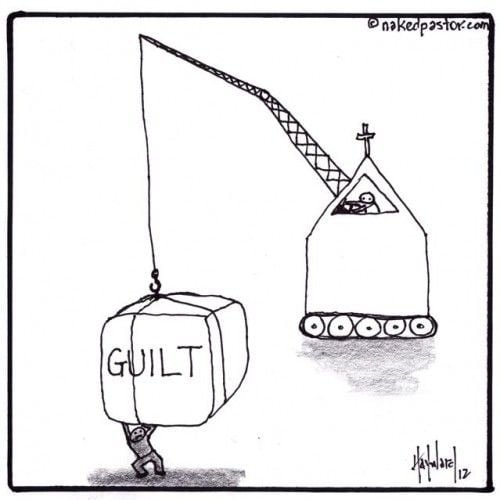

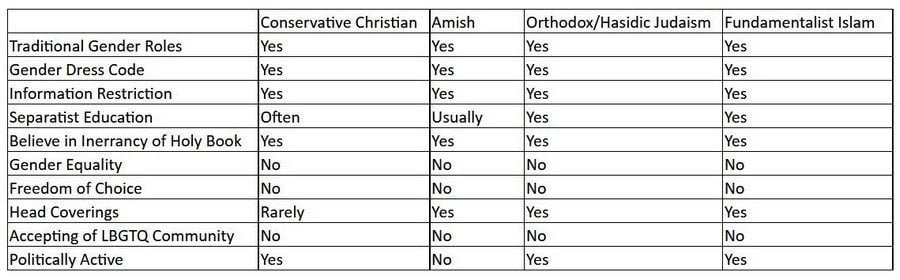

I look at all these groups and think, there’s no way I could live in one of those communities. After I graduated from high school, I did my best to escape the clutches of fundamentalist Christianity. Fortunately, I possessed a college degree from a highly ranked secular university and developed marketable skills, so I was able to support myself financially. Many in these communities, particularly women, are purposely raised without these skills, ensuring reliance on the community. It is my firm conviction that any group that purposefully restricts access to knowledge and education and discourages contact with outsiders is inherently harmful and potentially abusive. Those in power may thrive within these systems, but the systems themselves are designed to benefit those in power at the expense of the powerless.

I look at all these groups and think, there’s no way I could live in one of those communities. After I graduated from high school, I did my best to escape the clutches of fundamentalist Christianity. Fortunately, I possessed a college degree from a highly ranked secular university and developed marketable skills, so I was able to support myself financially. Many in these communities, particularly women, are purposely raised without these skills, ensuring reliance on the community. It is my firm conviction that any group that purposefully restricts access to knowledge and education and discourages contact with outsiders is inherently harmful and potentially abusive. Those in power may thrive within these systems, but the systems themselves are designed to benefit those in power at the expense of the powerless.