Guest post by MJ Lisbeth

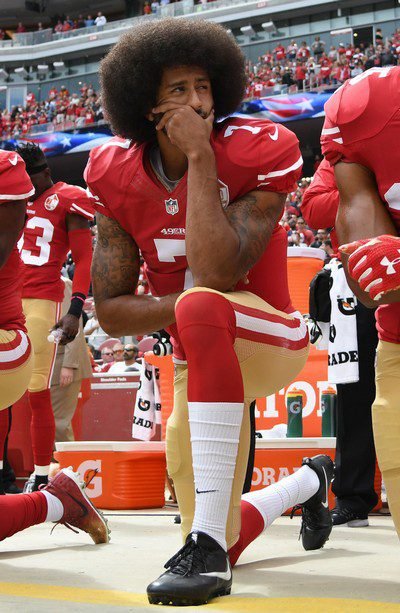

Two years ago, Colin Kaepernick did something that garnered far more attention than any game he played or pass he threw.

Those who disapproved of his gesture said he “refused to stand” during the National Anthem. On the other hand, those who approved, or simply supported his right to do so, said he “knelt” or “took to his knee.”

My response? “Well, at least he was on only one knee.”

From that position, he could leap up and run, if he needed to. Even though he’s a professional athlete, if he were on both knees, he’d have a hard time springing up and darting away.

That, of course, begs the question of why he would need to do such a thing. As an NFL quarterback who was, arguably, one of the best at his position for a couple of years, he almost certainly has the strength to fight off a would-be attacker, as well as the speed to run—and the reflexes to do either, or both.

Still, I was relieved not to see him on both knees for the same reason that, to this day, I cannot bear to see people in such a prone position — and why I never kneel.

The last time (that I recall, anyway) I knelt for any period of time was also the last time I had to see someone I love kneeling.

Even though she had to genuflect for only a moment, and I knelt only for a few more, I could barely keep myself from screaming. I couldn’t keep myself from crying the rest of that day.

It was an unusually hot day for May and, in spite of the air conditioning, everything seemed to be happening in the kind of haze that precedes storms and terrible, violent acts.

On the side of the aisle opposite from where I sat, a line of boys stood in their dark suits, almost none of which fit. On the side nearest me were a line of girls in loose white dresses that, on some, looked like oversized doll costumes.

They took one step down the aisle and stopped—except for the boy and girl at the front. It took them three or four steps to reach the altar. The boy, and the girl, knelt. The scream started to roil inside me.

The boy and girl turned their heads up. The priest mouthed the words. Even though I couldn’t hear him, I knew what they were: “Body of Christ.”

The boy whispered, “Amen,” and the priest placed a small round wafer in his mouth. He repeated this ritual with the girl. Then with the next boy and girl who came to the altar, and the ones after.

Some people made the sign of the cross for each kid receiving his or first communion. Others held their hands as in prayer. I cupped my hands in my best imitation of Durer’s sculpture—over my mouth. It was all I could do to keep the howl, the curses, I’d held from my childhood to that moment in my middle age.

Then she and another boy knelt in front of the priest. I nearly bolted out of that church. The reason I didn’t: My family, her family and all of their friends would be upset and demanded an explanation I couldn’t give them.

Truth is, even if I could’ve given it, I wouldn’t have. The words would not come until a few days later, after we had all gone back to our homes, some of us far away.

At that moment, I was never as afraid for anyone’s safety as I was for that girl — my niece — and the boy, whom I never knew, kneeling next to her. I had never seen the priest, either, before that day, and would never see him again. But I simply could not bear to see my niece, or that boy, kneeling — vulnerable — in front of him.

Even though her face wasn’t between his knees.

She and the boy rose to their feet, crossed themselves and walked back to the pews. Even though the priest did nothing to harm her — or him — I felt as if I had failed . . . to protect them . . . to save them . . . to protect and save myself.

After the mass, we all went to my brother’s house. Spreads of salads, sandwiches, chicken wings and breasts, burgers and other foods filled the tables and counters. I excused myself to go “to the bathroom” but snuck out the back door and across the yard into the woods, where I let out a long, howling wail and cursed out someone I hadn’t seen, or even thought about, since I was a child. Like my niece. Like that boy.

A few days later, my then-partner was talking about a wedding we would attend a few weeks later. In a church, of course. My partner — an atheist — noticed anger and bile rising through my face when she mentioned “church.”

“Hypocrites and pedophiles,” I grunted.

“What are you talking about?”

Then, as if — for lack of a better word — possessed, I sprang to my feet, stared past her, past everything and everyone and hissed, “Get your fucking hands off me, you motherfucker. God let you do it to me. But this time, I won’t.”

At least she knew I wasn’t talking to her — and that I wouldn’t attack her — which is probably the one and only time I can recall that she seemed not to know what to do.

Or maybe she did. Nothing. She did nothing. And I talked, for the first time, about the way a priest in my parish got me to kneel — between his legs.

I’ve talked about it only with a few other people since then. But I still haven’t gotten down on my knees — not for God, country or anything else.

Guest Post by Stephanie

Guest Post by Stephanie