Guest Post by Melody

A few days ago, I found myself commenting on Patheos, a part of which I will repeat here. It was about how God chose people — Judas, Jesus, etc. to play the role already laid out for them. Ultimately this makes free will more or less non-existent. The concept of free will combined with God’s complete foresight and knowledge often had puzzled me as a Christian.

If God already knew who would become his children and who wouldn’t, free choice didn’t really exist. Except God (and everyone else) said it did. I never could make sense of it and I so wanted to understand — that’s just how I’m wired — because I loved God and took it very seriously.

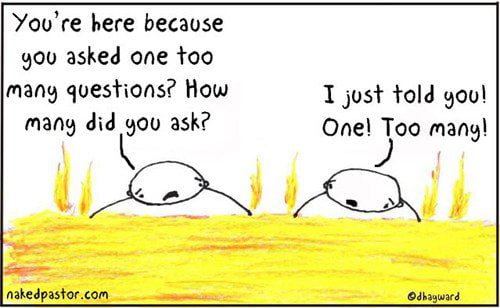

And then I wrote the following: “That’s one of the things that hurts, by the way, because questioning children and adults are seen as rebellious or irritating, whereas the questions came from a deep longing to understand and not from a negative or rebellious place at all. It did, however, ultimately show me that there weren’t any good answers to my questions.”

So I thought perhaps I should let it all out and rant for a while about this. I had questions, loads of them, as a child, teen, and adult. I had and still have a thirst for knowledge and I always assumed this to be a good thing. You should use your mind, shouldn’t you? Your reasoning, your God-given gifts?

Perhaps not….

Therefore, it can hurt a lot when people — parents, teachers or preachers — assume you are just being irritating and annoying for the sake of it; that you’re putting your finger on something to challenge their authority or to make them feel stupid, when all you are doing is trying to really understand and you are very seriously trying to find the truth — stubbornly so.

It doesn’t make for pleasant conversation, that’s for sure.

It does make for confused believers, however. Over the years, I learned that some questions were not allowed, that they were seen as challenging God himself, that I wasn’t supposed to ask them. In the end, I self-censored my questions and stopped myself from asking them out loud. It didn’t meant they had left me though. They had just gone underground.

It also made me disappointed. These authorities were supposed to have the answers and help us, the believers, in finding them. If God had all the answers, shouldn’t his representatives be able to answer? And if neither God, nor his representatives, provided one with any answers, is it really such a surprise people ultimately leave their faith?

You’d think they would at least understand that!

It has taught me that there are different kinds of believers — that some of them are okay with not knowing, with accepting all the unknowns about God; that not knowing doesn’t bother them in the least. That, presumably, they get a lot of other things out of their faith: community, a sense of belonging, meaning etc.

But that there are also believers who do long to know — quite desperately, even. They find their way to God through knowledge and if that method fails, will begin to look at faith and religion differently.

They become the kind of believers who then become what they have been accused of for ages already: rebellious and skeptical.

How were your doubts addressed by (church) authorities or family? Did you feel falsely accused of being rebellious or irritating when asking uncomfortable but honest questions?

Would you like to write a guest post? Please send me an email and let let know of your interest.