Guest Post by MJ Lisbeth

‘History’ Stephen said, ‘is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.’

That is one of Jonathan’s favorite quotes. Knowing what I’ve come to know about him, it’s not difficult to understand why: the history from which Stephen is trying to awake in James Joyce’s Ulysses is the same history in which Jonathan (not his real name) came to be. To some extent, it is also my history.

Jonathan is a co-worker of mine, and we have been working on a project. That is how I have come to know a bit about him, and he’s come to know a few things about me. It shouldn’t have surprised either of us to find parallels in our backgrounds.

We both grew up in communities where nearly everyone went to mass in the same Catholic parish. My education was remarkably similar to his, though I received mine in a Catholic school across the street from the church and his took place in a “public” school. Most of my teachers were Dominican sisters. I got a heavy dose of religious instruction and was brought, with my schoolmates, to confession every Friday in the church. We now chuckle about standing on line at the confessional and thinking about what sins we would confess — at age eight.

As an altar boy, I served in the First Holy Communion mass for one of my schoolmates. A couple of weeks later, I served at the funeral of her older brother who was killed in Vietnam. I also served at my brother’s confirmation and, a few days later, the wedding of an older sister of a boy who was confirmed with my brother. I always felt that much in the lives of our community centered on the church.

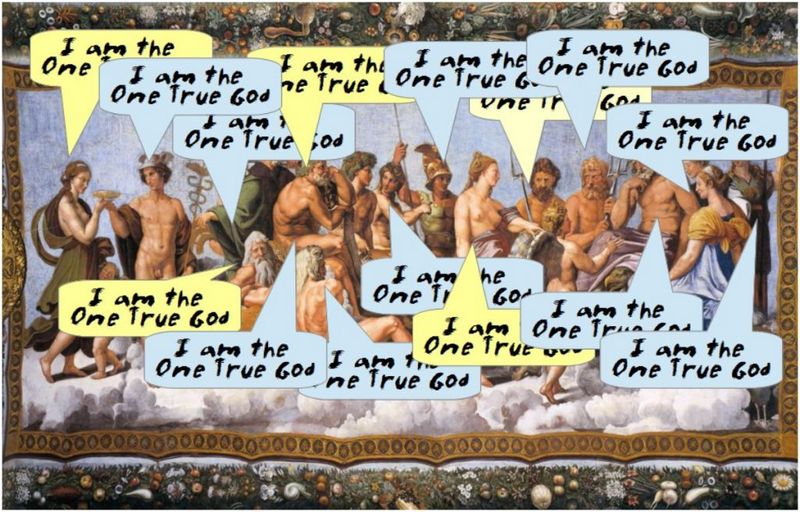

I would later learn that there are many such communities all over the United States. The churches at their cores might be Baptist, Lutheran, Methodist or some other denomination. They nonetheless dominate the social as well as spiritual lives of those hamlets, villages, towns and urban enclaves in much the same way my former Catholic church cast its net around my old neighborhood.

Even so, those communities, numerous as they are, could never compare to what Jonathan lived in. It’s something that, even with my background, I have difficulty imagining: a whole country in which everyone belongs to, if not the same parish, then at least the same church. “In Ireland, you didn’t just go to church,” he explains. “You were always in the church, wherever you went, whatever you did.”

Jonathan grew up in Ireland during the 1980s and early ‘90s: two decades or, if you prefer, a generation, after my upbringing. At that time, the Catholic Church was still the de facto government, education system and provider of social services. “There really wasn’t any secular education in Ireland at that time,” he observes. Even most “public” schools, like the one he attended, were run, in fact or in essence, by the church. He got an hour a day of religious (indoctrination) instruction, as I did. That teaching was compulsory in all Irish schools of the time, he says. On the other hand, had my parents enrolled me in the public school of our urban American neighborhood, religious education would not have been part of my curriculum.

Another striking similarity between my education and his is that, while instruction in most subjects was rigorous, it included nothing about our bodies—or, of course, evolution. Had I attended public school, I might have learned something about Darwin’s ideas though, to be fair, given the times, I might not have had anything resembling sex education. In contrast, there was really no way Jonathan, in his country, in his time, could have learned anything about the way humans or other animals evolve, reproduce or take care of themselves.

Jonathan left Ireland in the mid-90s, just before it experienced its first (and perhaps only) economic boom — and the church started to lose its grip. He’s been back a few times, mainly to visit family and friends, but has no regrets about leaving, he says. For one thing, he pursued graduate studies and a career that would have been all but unavailable in the Ireland of his youth. Oh — and he met and married a beautiful biracial woman.

Also, he says, even though many of Ireland’s young today find the Church, and religion generally, “irrelevant,” there is still a “residue of religiosity,” mainly among older people and in the countryside. That is one reason, he says, the country was “convulsed” by the sex abuse scandals in ways that people in other European countries or the US can barely imagine. While the young don’t attend church and many don’t believe, the Church still runs schools like the one Jonathan attended. And hospitals. And orphanages. And many other organizations and institutions on which people depend for finding employment and housing, getting healthcare and other things most people consider part of living.

The church had an even tighter grip on Ireland during Jonathan’s youth, not to mention in earlier times. In few other countries was Catholicism as much a part of a person’s identity as it was in Ireland until a generation or so ago. One reason the Church was able to take such a hold of the populace is that, for centuries, their British occupiers tried to obliterate all signs of native culture. Speaking, let alone teaching, Gaelic became illegal. As in Poland during the Cold War and earlier occupations, the Church was the only organized opposition to oppression, mainly because it was the only opposition that had help from outside the country: Priests could go to France, Spain or Germany for their training. Thus, for the people, their religion became a bulwark against a foreign power that sought to subsume their identities. That, from what I’ve read — and what Jonathan has told me — is the reason the Irish held so fiercely to a religion that did as much to oppress them as any occupying army.

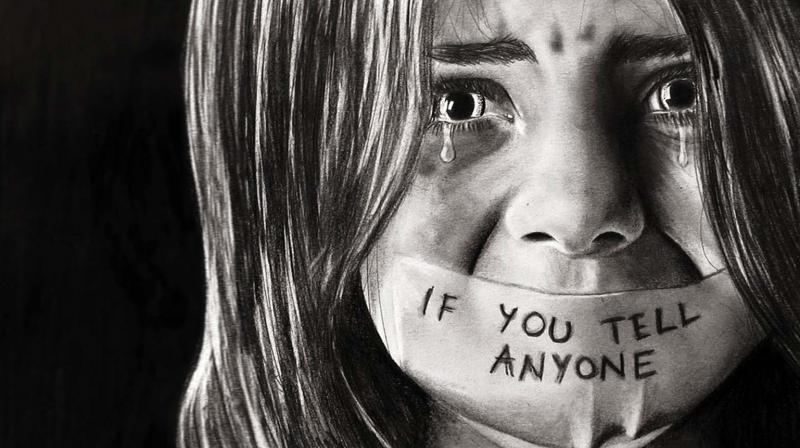

If a hierarchical structure like the church can use its representatives’ putative relationship with God to exploit those who are younger, weaker, poorer or in any other way more vulnerable than themselves in a country like the United States, the horrors they could inflict on poor Irish people are unimaginable to most of us. Even the most devout or impoverished American Catholics have never depended on the church for their identity or even sustenance in the way an everyday Catholic in Ireland did just a generation ago, i.e., in Jonathan’s time.

The “residue” of which Jonathan speaks was left by that captivity. Let’s call it what it is: slavery. Just as African-Americans still must extricate themselves from the detritus of their ancestors’ bondage, the Irish today are still living with the debris of the Church (and colonialism). And, although the young have made great strides (for example, four years ago Ireland became the first country to legalize same-sex marriage by popular vote, largely because of the young), they are still awakening to the nightmare of their history: their parents’ and grandparents’ oppression by the church.

Waking from a nightmare is difficult. It is not — contrary to how it may seem — the waking itself that’s difficult. Rather, it’s the nightmare that causes difficulty because it terrifies and tires us. At least the nightmare can end if we wake up.

And so it is with the church sex-abuse scandals, in Ireland and elsewhere. People see it as a tragedy or scandal when it comes to light. But the real tragedy, the real scandal, as Jonathan points out, is that the sex abuse went on, in the Magdalene orphanages, in the monasteries, in the schools and, of course, in the parishes, for centuries—during Jonathan’s lifetime, my lifetime, his parents’ and grandparents’ lifetimes, their grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ lifetimes, and during the lifetimes of their forebears. They lived the nightmare; we have lived it; now we are waking from it. Jonathan knew he had no other choice. Nor do I.

Share This Post On Social Media:

Guest post by MJ Lisbeth

Guest post by MJ Lisbeth