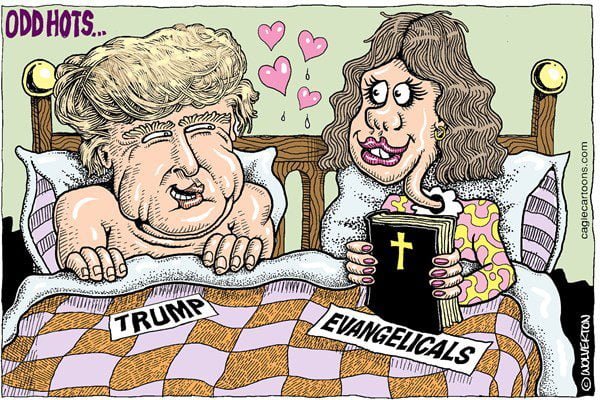

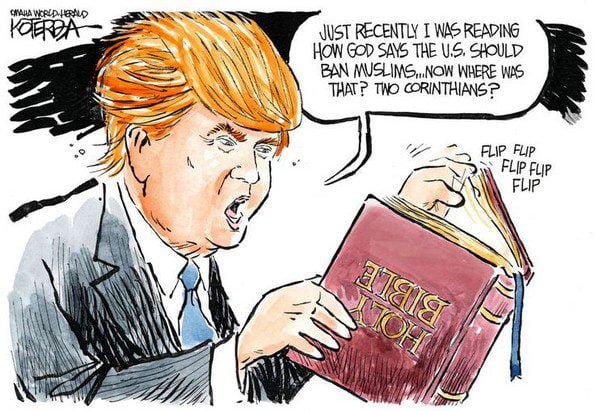

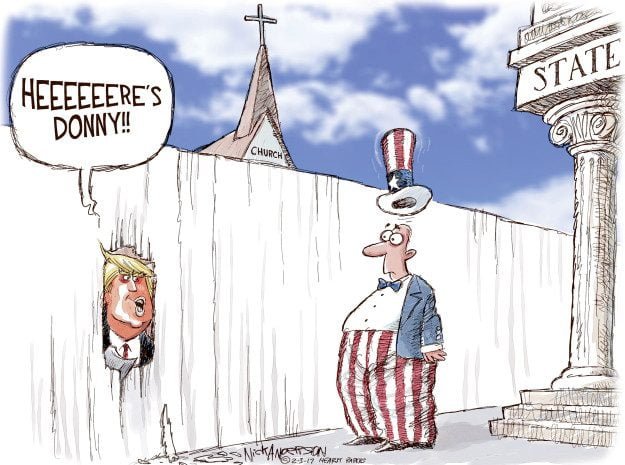

Evangelical Christians continue to represent a sizeable percentage of the current president’s base support. To those who have watched evangelicals spend “the last 40 years telling everyone how to live, who to love,” and “what to think about morality,” the continued alliance with this president makes evangelicals the “biggest phonies” in all of politics. Indeed, the behind-the-scenes details of how a “thrice-married, insult-hurling” president obtained the endorsement of the evangelical hierarchy are as lewd and hypocritical as one might expect.

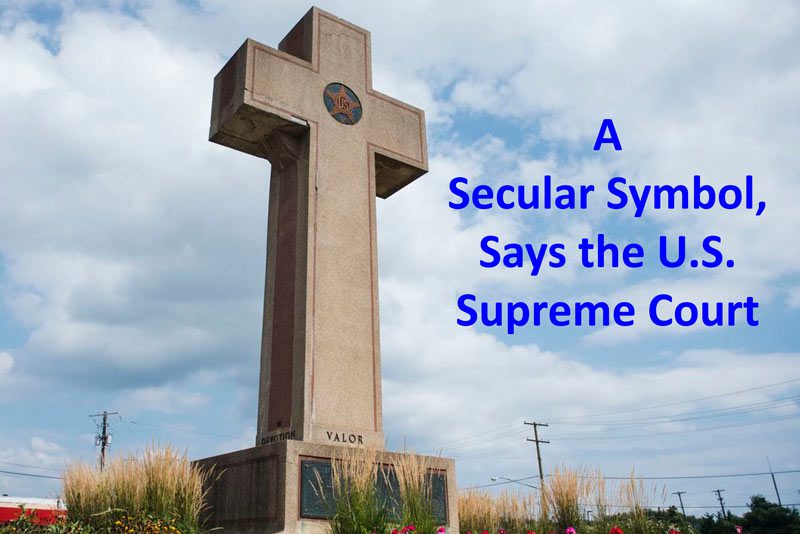

As much as the hypocrisy of evangelicalism can be mocked and exposed however, there exists a kernel of truth lurking behind the claim that evangelicals are supporting this president out of fear. It is simply impossible to deny that institutionalized persecution of religious ideas by public universities has occurred. Thankfully, this persecution has been continuously challenged and overturned in the courts.

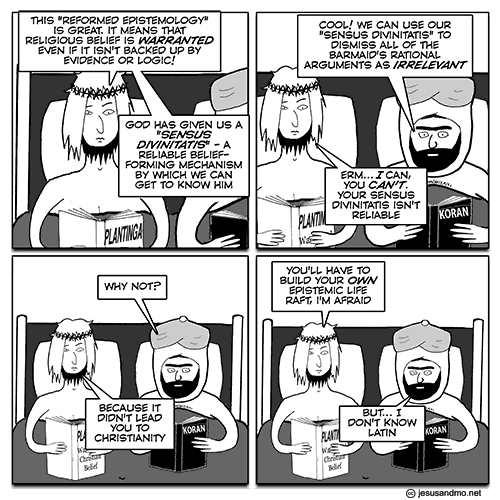

The fact that persecution of religious ideas can and has occurred in our society however, does not even remotely suggest that intolerance is a uniquely “secularist” problem. In fact, intolerance of dissent and censorship of opposing views has been a general feature in religious institutions for thousands of years. Moreover, the same intolerance and censorship evangelicals claim they hate so much when it occurs in “secular” institutions is expressly embraced at the largest Christian colleges in the United States today, such as Liberty University. Does this past and current existence of intolerance in religious institutions mean that religion is inherently intolerant? No, because human bias exists generally in all human institutions, a fact the framers of the Constitution knew all too well and the exact reason why they chose to embrace secularism.

….

For example, David French, who I would argue is a moderate evangelical, has argued recently that we should be wary of European immigration because those countries have a “secular-bias” that will “alter American culture in appreciable ways.” In answering this nonsense from French, it is important to acknowledge that such a statement amounts to nothing less than vile bigotry.

To illustrate, imagine for one second how French would react if a liberal pundit on MSNBC said we should avoid immigrants from Christian-majority countries because America is steadily becoming more secular. Is there any doubt French would find such a statement to be a reflection of bigotry against Christians based on ridiculous notions that they are somehow incapable of assimilating into American culture? Yet he felt no issue disparaging and demeaning immigration from a whole continent based entirely on whether they held certain religious beliefs or not. Why? Because for all too many evangelicals, non-belief is simply not viewed with the same respect as religious belief, despite the fact that our Constitutional free conscience liberty makes no distinction. Put simply, it is nothing less than disgraceful the level of bigotry that evangelicals impose on the none-religious. Until and unless the religious stop lying about the nature of secularism, falsely depicting it as the ultimate evil, I fear such bigotry will continue to increase.

— Tyler Broker, Above the Law, The False Demonization Of Secularism, July 30, 2019