It’s the most common question religious folks pose to atheists: “Where do you get your morals?”

Whether at a dinner party or class reunion, a PTA meeting or a pig pickin’, whenever God-fearing people find out that we don’t believe in the Lord, don’t believe in an afterlife, don’t attend church, synagogue, mosque, or temple, don’t follow a guru, don’t obsess over ancient scriptures, and don’t care much for preachers or pontiffs, they immediately inquire about the possible source of our morality — which they find hard to fathom.

And the question “Where do you get you morals?” is usually asked with an embedded implication that morality obviously comes from God and religion, so if you don’t have either, then you must have no source for morality. On top of this problematic implication, there is often an accompanying judgmental, sneering tone; it’s as if what they really want to say is “You must be an immoral lout if you aren’t religious and don’t believe in God.”

To be fair, not everyone who asks atheists where they get their morals is implying something unkind. Given that religion has so fervently, forcefully insisted that it is the only source of morality for so many centuries, many people just honestly and naively believe that to be the case. Thus, not having thought too much about it, they are genuinely curious about where a person gets his or her morals, if not from religion.

But even if the question is asked in total unprejudiced earnestness, it is still a rather odd query. After all, “Where do you get your morals?” suggests that morals are things that people go out and find in order to possess. Like shoes. Or a new set of jumper cables. It implies that people are living their lives, doing this and that, and then at some point, they decide to drive downtown or go online and get ahold of some morals — as if ethical tenets and moral principles were consciously adopted in some sort of deliberate process of acquisition.

Morality, however, doesn’t really work that way. While people may deliberately choose to get their donuts from a certain shop or decide to get their dog from a certain pound, when it comes to the core components of our morality — our deep-seated proclivities, predilections, sentiments, values, virtues, and gut feelings in relation to being kind and sympathetic — these things are essentially within us. They are an embedded, inherited part of us. We don’t go out and “choose” them, per se. Sure, we may change our minds about a certain social issue after learning more about it and critically reflecting upon it; we may develop a love or distaste for something after having had certain new experiences in relation to it; we may start to live our lives differently, with different ethical priorities, after we marry a certain person and cohabitate with them for an extended period of time; we may find our political positions shift when we move to a new state or country and live there for a while.

However, when it comes to our underlying morality, it is not generally something that we “get” in a conscious, deliberate, choosing way. Rather, our deep-seated sense of how to treat other people, our capacity for empathy and compassion, our desire for fairness and justice — these are things that we naturally manifest: our morals have been inherited from our evolutionary past, molded through our early childhood nurturance, enhanced and channeled through cultural socialization, and as such — to paraphrase sociologist Émile Durkheim — they “rule us from within.”

What exactly is it that rules us so — morally speaking? And what are the specific foundational sources of our moral proclivities and ethical tendencies? There are four: 1) our long history as social primates, evolving within a group context of necessary cooperation; 2) our earliest experiences as infants and toddlers being cared for by a mother, father, or other immediate caregivers; 3) unavoidable socialization as growing children and teenagers enmeshed within a culture; and 4) ongoing personal experience, increased knowledge, and reasoned, thoughtful reflection.

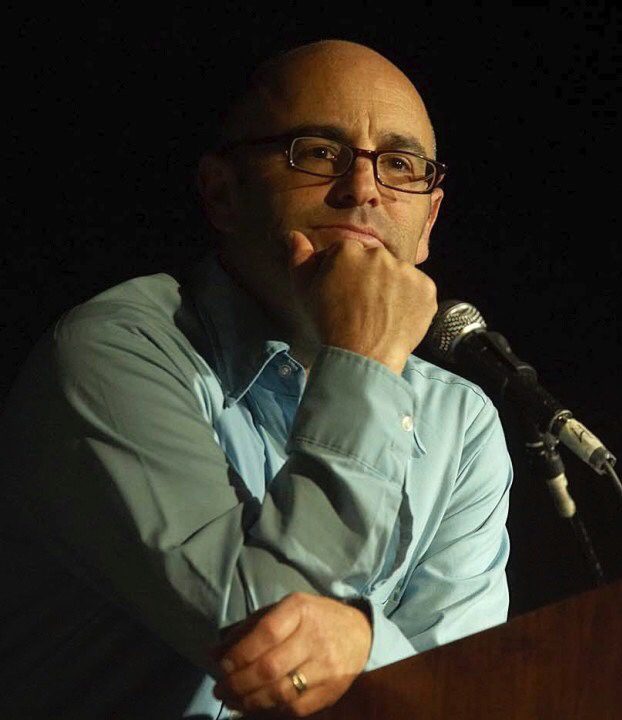

— Phil Zuckerman, What It Means to Be Moral: Why Religion Is Not Necessary for Living an Ethical Life

Purchase What It Means to Be Moral: Why Religion Is Not Necessary for Living an Ethical Life