The Fort Worth Star-Telegram published a four-part investigative report today by Sarah Smith detailing the rampant sexual abuse found in the Independent Fundamentalist Baptist (IFB) church movement. I have talked with Sarah Smith several times over the years. I appreciate her dogged and thorough reporting on what many of us gave known for years: the IFB church movement has just as big a problem among its leaders with rape, sexual abuse, and sexual misconduct as does the Roman Catholic Church. Two decades in the making, reckoning day has arrived for IFB churches, pastors, and colleges. I have no doubt Smith’s exposé will be widely reported.

I can’t wait to see how various IFB luminaries respond. According to Smith’s report, thus far her exposé has been met with silence. For those of us raised in the IFB church movement, this comes as no surprise. I hope law enforcement will pay attention to Smith’s report and prosecute these predators to the fullest extent of the law. Sadly, the statute of limitations will likely hinder criminal prosecution of many of the allegations detailed in Smith’s story. Perhaps, then, victims will turn to civil courts to litigate their claims. Nothing like hitting Independent Baptists where it matters: the offering plate.

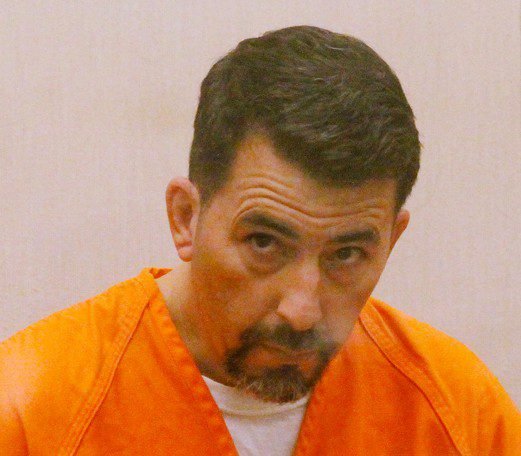

What follows is an excerpt from Smith’s report. This excerpt details the alleged predatory and criminal behavior by David Hyles. At the end of this excerpt, you will find links to posts I have written about David and his father, the late Jack Hyles — pastor of First Baptist Church in Hammond, Indiana.

Joy Evans Ryder was 15 years old when she says her church youth director pinned her to his office floor and raped her.

“It’s OK. It’s OK,” he told her. “You don’t have to be afraid of anything.”

He straddled her with his knees, and she looked off into the corner, crying and thinking, “This isn’t how my mom said it was supposed to be.”

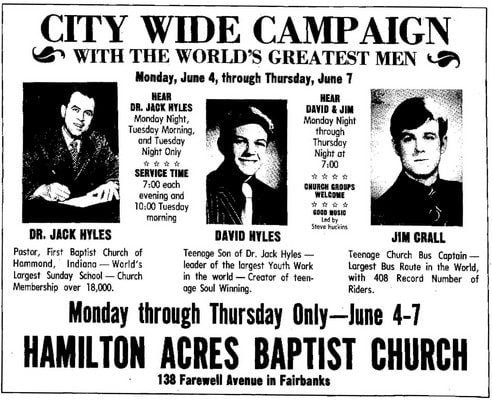

The youth director, Dave Hyles, was the son of the charismatic pastor of First Baptist Church of Hammond, Indiana, considered at the time the flagship for thousands of loosely affiliated independent fundamental Baptist churches and universities.

At least three other teen girls would accuse Hyles of sexual misconduct, but he never faced charges or even sat for a police interview related to the accusations. When he got in trouble, Hyles was able to simply move on, from one church assignment to the next.

….

In Joy Evans Ryder’s mid-1970s church-driven world, skirts had to go past knees, men and women had to be separated by six inches, and a good daughter’s gift to her father was to save her first kiss for the altar.

A father himself, Jack Hyles was nicknamed the “Baptist Pope” for the sway he held over the nationwide independent fundamental Baptist movement from his power base in small-town Indiana.

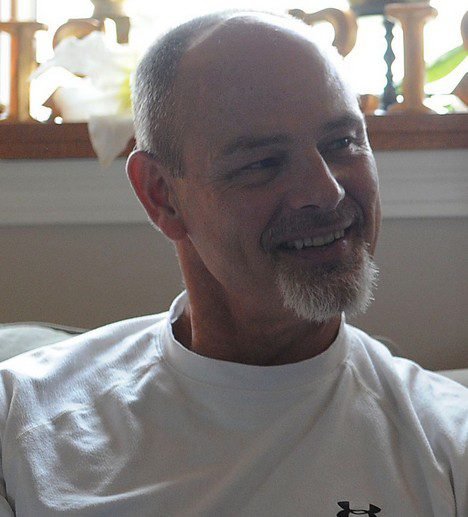

His son Dave was tall, skinny and already balding by his mid-20s. He had his father’s eyes that pulled down at the corners. No one would have called him traditionally handsome, but he had his father’s ability to make you feel a part of the in-crowd with a compliment or sarcastic joke. And he could just as easily push you out with a cutting insult.

Dave Hyles had taken an interest in Ryder when she was 14, and it scared her.

One Sunday morning after service, she stood in line to speak to Jack Hyles — the most important person in her world — about his son’s repeated calls to her house. The attention made her uncomfortable, she said.

The pastor sat at his desk and took her in for a moment.

“Joy, you’re not special,” he said. “He does that with everyone. So don’t think he’s trying to do anything with you.”

Not long after, she was raped by Dave Hyles. It continued for two years.

Reached by phone, Dave Hyles declined to comment. The Star-Telegram followed up by sending him a list of written questions. He did not respond. Jack Hyles died in 2001.

At 16, Ryder thought about suicide, fearing she might be pregnant with Dave Hyles’ child. She imagined ramming her car into a telephone pole or a tree, killing her and the baby.

She didn’t think about going to police.

“I went to somebody I thought would be my protector,” Ryder said. “Not my dad, because this shows you how we were taught to think about our pastor, Dr. Hyles.”

Dave Hyles had warned her to stay quiet or he’d get her parents fired. Her father was president of Hyles-Anderson College, a school started by and run from First Baptist Church. Her mother was the school’s dean of women.

To her friends, Ryder looked happy. She was popular, secure in her social status, and had a spot in the church school’s coveted choir, called Strength and Beauty. She liked to run off to the mall with friends every chance she got and had her light-brown hair feathered, Farrah Fawcett-style.

But she was also angry and ready to rebel against the system that entrapped her. She sneaked to movies, wore pants and swiped cigarette packs, all verboten in the church.

At 17, Ryder snapped. She called her parents from a payphone at the church school and told them to meet her at home. She told them everything.

The next time she met Hyles, her father would follow.

He drove behind her to a Holiday Inn, and waited in his car as he watched Ryder walk into a first-floor room and shut the door.

“I’m leaving,” Ryder told Hyles.

He asked what she meant.

“I’m leaving,” she repeated. “I told my parents, and my dad is outside.”

Hyles pulled back the curtain and saw her father’s car. She says he shoved her against the wall, his forearm pressed on her throat.

“What have you done to me? You’ve ruined my ministry. How could you do this to me?’”

He let her go and paced the room. Ryder walked out, got in her car and drove home. Her father followed her. He didn’t confront Hyles.

He did, however, go to Jack Hyles, who dismissed the report about his son because Ryder’s father didn’t record Dave Hyles’ license plate number.

Her father dropped the subject.

Ryder’s father, Wendell Evans, wished he could do it over, he said 35 years later in a notarized statement provided to the Star-Telegram, taken because Ryder was seeking evidence to take to the church.

At the time of the abuse, Evans’ career was blossoming in the church. Pushing Hyles, his boss, on the allegations would have been difficult, he said.

“I mean, Hyles and I were still good friends,” he said. “We marveled sometimes that our friendship survived this situation.”

But in an interview with the Star-Telegram, Evans was not so forgiving of Dave Hyles. He regrets not calling the police on him.

“I think it’s remarkable that in 40 years, Dave didn’t find time to ask forgiveness from his victims and their parents,” said Evans, now 83.

It was not the first time Jack Hyles heard allegations against his son, nor would it be the last. One woman alleged Dave Hyles raped her at 14 when she attended the church’s high school, years before Ryder. The woman’s 10th-grade teacher also confronted Jack Hyles about his son, only to be brushed off.

Dave Hyles’ ministry wasn’t ruined. Instead, he got promoted.

A few months after Evans and Jack Hyles spoke about the encounter at the Holiday Inn, Dave Hyles became the pastor at Miller Road Baptist Church in Garland, Texas — the church his father led before moving to Indiana. Jack Hyles would later say he never recommended his son to any church, but deacons and staffers at Miller Road said their search committee called Jack Hyles about Dave. No one heard any warnings.

Two more women would accuse Dave Hyles of molesting them in Texas. One woman, who went to Hyles-Anderson for college, said she tried to tell Jack Hyles what had happened. He told her not to tell anyone else.

Then, she said, he kicked her out of his office.

….

Dave Hyles left victims across the country. They are still in recovery.

In the 1970s and ’80s, with his dad’s church among the biggest in the country, Hyles cut a celebrity-like figure in the movement — and took advantage of it.

Rhonda Cox Lee felt special when Hyles noticed her out of the hundreds of kids who attended his dad’s church.

The first time anything sexual happened, she said, they were in his office. He sat at his desk, she sat across from him on a chair. He walked around the desk and placed her hand on his groin.

“Do you feel that?” he asked.

At first she thought it was some sort of spiritual test. He was a man of God, after all, and even though it felt wrong, he wouldn’t ask her to do anything wrong. Several meetings later, their clothing came off. She was 14. It felt wrong, she said, but she knew it had to be what God wanted.

“He compared himself to David in the Bible and how he was anointed, and said this is what I was supposed to do,” Lee said. “I was supposed to take care of him because he was the man of God.”

Hyles, she said, alternately promised her that they would be together once she turned 18 and warned her not to tell anyone in the church because if she did, the church would split, America would go to hell, and the blood of the unsaved would be on her hands.

Brandy Eckright went to Hyles for counseling at his church in Garland, Texas, when she was 18, after being molested as a child. She said he soon took advantage of her, and they had sex for the first time in 1982.

“Dave, I thought he was a God,” said Eckright, who like Lee had never gone public with her allegations against Hyles. “I thought if I got pregnant by Dave Hyles, it would be like having God’s baby.”

At 54, Eckright can barely talk about what happened. She’s survived three suicide attempts. She works as a cashier and said she can barely hold down the job.

In 1984, Hyles left Miller Road Baptist Church in Garland after a janitor found a briefcase stashed with pornography featuring Hyles and married female members of the congregation, ex-members said. He and his new wife went back to live near First Baptist Church of Hammond, Indiana, and then moved again.

Dave Hyles has managed to stay out of handcuffs.

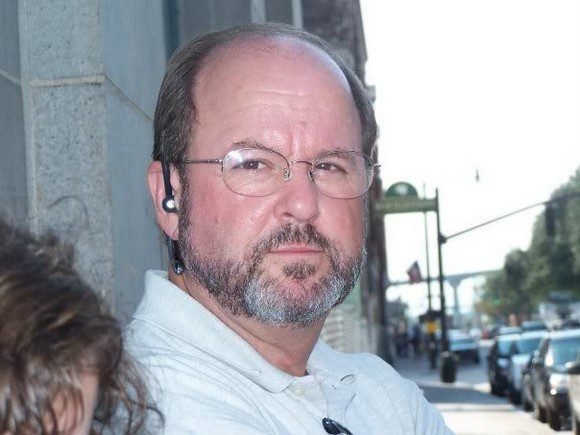

Today, he runs a ministry for pastors who have fallen into sin, supported by Family Baptist Church in Columbia, Tennessee, pastored by David Baker.

In 2017, Joy Evans Ryder’s brother emailed Baker, outlining Hyles’ alleged crimes against his sister. Baker took five words to reply: “Thank you for your concern.”

Baker, a Hyles-Anderson College graduate and a military veteran, said he thinks Dave Hyles has been unfairly blamed. Hyles, Baker said, is a good man, with a strong marriage who has helped many people through his ministry.

“He’s someone who made mistakes years ago, and through that brokenness and God restoring him, wants to use what he’s been through to help others,” Baker said. “I’m not going to debate anybody about those issues.”

Dave Hyles, with gray hair and a beard, is pictured on his Facebook page in a red polo shirt and square-rimmed glasses similar to the ones his father so iconically wore. He sends posts in his private Facebook group, Fallen in Grace Ministries, contemplating the nature of sin and restoration.

In a September missive forwarded to the Star-Telegram, Hyles wrote that he had enemies, people who harassed him and slandered him. “In fact, I have come to realize that there is nothing we could do to satisfy them. The more we tried the less we would satisfy them,” he wrote. “So, what exactly do they want?”

Guest Post by Stephanie

Guest Post by Stephanie