One of the hardest things I had to come to terms with was the fact that my parents raised me in a cult; that I was a member of a cult; that I attended a college operated by a cult; that I married a girl who was also a member of a cult; that I spent twenty-five years evangelizing for a cult and pastoring its churches. Worse yet, as devoted cult members, my wife and I raised our six children in the way of the cult, in the truth of the cult, and in the life of the cult. All religions, to some degree or the other, are cults. The dictionary describes the word “cult” several ways:

- A system of religious beliefs and rituals

- A religion or sect that is generally considered to be unorthodox, extreme, or false [who determines what is unorthodox, extreme, or false?]

- Followers of an unorthodox, extremist, or false religion or sect who often live outside of conventional society under the direction of a charismatic leader

- Followers of an exclusive system of religious beliefs and practices

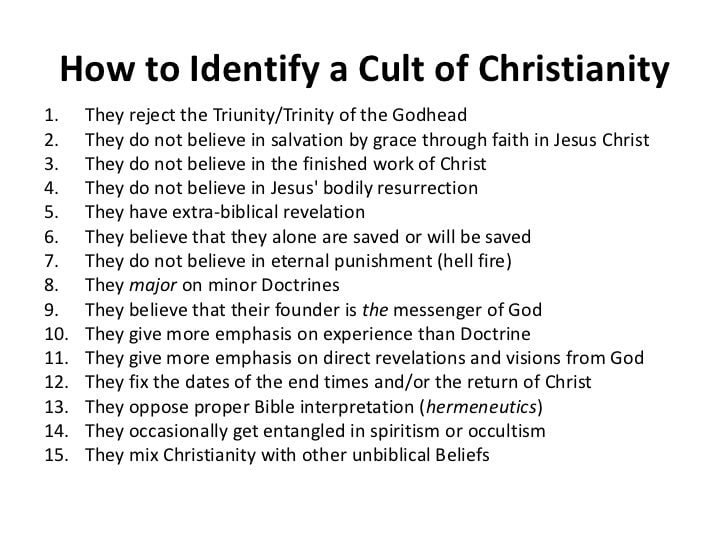

As you can see from these definitions, Christianity is a cult. In particular, the Independent Fundamentalist Baptist (IFB) church movement and Evangelicalism, in general, are cults. I rarely use the word “cult” when describing Evangelical beliefs and practices because the word means something different to Evangelicals. In their minds, sects such as The Church of Christ of Latter-day Saints, Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Unification Church, and the Roman Catholic Church are cults. Some Evangelical churches bring in cult specialists to teach congregants about what is and isn’t a cult. Countless Evangelicals have read Walter Martin’s seminal work, The Kingdom of the Cults. Martin’s book was considered the go-to reference work when it came to cults. Martin defined a cult this way: a group of people gathered about a specific person—or person’s misinterpretation of the Bible. In Martin’s mind, any group of people who follow a person’s misinterpretation of the Bible is a cult. Of course, Martin — a Fundamentalist Baptist — was the sole arbiter of what was considered a misinterpretation of the Bible. Written in 1965, The Kingdom of the Cults included sects such as Seventh-day Adventism, Unitarian Universalism, Worldwide Church of God, Buddhism, and Islam. Martin also believed certain heterodox Christian sects had cultic tendencies. I am sure that if Martin were alive today, a revised version of The Kingdom of the Cults would be significantly larger than the 701 pages of the first edition. Martin and his followers, much like Joseph McCarthy, who saw communists under every bed, saw cultism everywhere they looked — except in their own backyards, that is.

Over the years, I have heard from numerous college classmates and former parishioners who wanted me to know that they had left cultic IFB churches and joined up with what they believed were non-cultic Evangelical churches. These letter-writers praised me for my exposure of the IFB church movement, but they were dismayed over my rejection of Christianity in general. In their minds, I threw the proverbial baby out with the bathwater; if I would just find a church like theirs I would see and know the “truth.” I concluded, after reading their testimonies, that all they had really done is trade one cult for another.

Take, for example, my college classmates. Most of them were raised in strict IFB homes and churches. Some of them had pastor fathers. Later in life, they came to believe that the IFB church movement, with its attendant legalistic codes of conduct, was a cult. As I mentioned in my post titled, Are Evangelicals Fundamentalists? there are two components to religious fundamentalism: theological fundamentalism and social fundamentalism. Most Evangelicals are both theological and social Fundamentalists, even though some of them will deny the latter. My college classmates, in leaving the IFB church movement, distanced themselves from social fundamentalism while retaining their theological fundamentalist beliefs. They wrongly believe that by rejecting the codes of conduct of their former churches, they were no longer members of a cult. However, their theology changed very little, and often they just traded a “legalistic” code of conduct for a “Biblical” one. These “non-legalists” revel in their newfound freedoms — drinking alcohol, going to movies, wearing pants (women), saying curse words, smoking cigars, having long hair (men), listening to secular music, using non-King James Bible translations, and having sex in non-missionary positions, to name a few — thinking that they have finally escaped the cult, when in fact they just moved their church membership from one cult to another. When the core theology of their old church is compared to their new church, few differences are found.

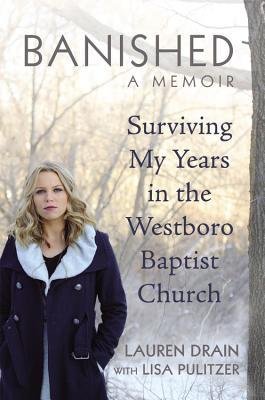

I can’t emphasize this enough: regardless of the name on the door, the style of worship/music, or ecclesiology, Evangelical churches are pretty much all the same. Many Evangelicals consider Westboro Baptist Church to be a cult. However, a close examination of their theology reveals that there is little difference between the theology of the late Fred Phelps and his clan and that of Southern Baptist luminary Al Mohler and his fellow Calvinists. Ask ten local Evangelical churches for copies of their church doctrinal statement and compare them. You will find differences on matters of church government, spiritual gifts, and other peripheral issues Christians perpetually fight over, but when it comes to the core doctrines of Christianity, they are in agreement.

Calvinists and Arminians — who have been bickering with each other for centuries — will vehemently disagree with my assertion that they are one and the same, but when you peel away each group’s peculiar interpretations of the Bible, what you are left with are the historic, orthodox beliefs expressed in the creeds of early Christianity. There may be countless flavors of ice cream, but they all have one thing in common: milk. So it is with Evangelical sects and churches. During what I call our wandering years, Polly and I attended over one hundred Christian churches, looking for a church that took seriously the teachings of Christ. We concluded that Evangelical churches are pretty much all the same, and that the decision on which church to attend is pretty much up to which kind of ice cream you like the best. No matter how “special” some Evangelical churches think they are, close examination reveals that they are not much different from other churches. This means then, that there is little to no difference theologically among Christian cults. Codes of conduct differ from church to church, but at the center of every congregation is the greatest cult leader of all time, Jesus Christ. (See But Our Church is DIFFERENT!)

Go back and read the definitions of the word cult at the top of this post, and then read Walter Martin’s definition of a cult/cult leader. Is not Jesus a cult leader? Is not the Apostle Paul also a cult leader? Is not the sect founded and propagated by Jesus, Peter, James, John, and Paul, and propagated for two thousand years by pastors/priests/evangelists/missionaries a cult? Is not the Judaism of the Old Testament a blood cult, as is its offspring, Christianity? Surely a fair-minded person must conclude that Christianity is a cult. Regardless of denomination, peculiar beliefs, and different codes of conduct, all Christian churches are, in effect, cult temples, no different from the “pagan” temples mentioned in the New Testament.

Disagree? By all means, use the comment section to explain why your Christian/Evangelical/IFB sect/church is not a cult, but other sects and churches are. Why should your beliefs and practices be considered truth and all others false? Hint, the Bible says is not an acceptable answer (nor are worn-out presuppositional tropes). All cultists appeal to their religious texts for proof that their beliefs and practices are “truth.” Why should anyone accept your sect’s book as “truth?” Why should anyone believe that Jesus is the way, truth, and life or that the Christian God is the one true God?

Bruce Gerencser, 68, lives in rural Northwest Ohio with his wife of 47 years. He and his wife have six grown children and sixteen grandchildren. Bruce pastored Evangelical churches for twenty-five years in Ohio, Texas, and Michigan. Bruce left the ministry in 2005, and in 2008 he left Christianity. Bruce is now a humanist and an atheist.

Your comments are welcome and appreciated. All first-time comments are moderated. Please read the commenting rules before commenting.

You can email Bruce via the Contact Form.